As the Vagrancy Act is set to be scrapped, Dr Dave Hitchcock explains its history and influence for the last 200 years. Yesterday, the Labour government announced that it was […]

Could a standing army tackle riots and deliver order?

Paul Swallow looks at how France have developed their standing armies for dealing with riots, and asks if it’s possible for the UK to do the same.

New legislation prompts organisations to improve staff training in terrorism incidents

Jessica Bombasaro-Brady, Senior Lecturer in the School of Law, Policing and Social Sciences, discusses The King’s Speech this week which highlighted new legislation to keep people safe, reducing the risk to the public from terrorist attacks at public venues.

Policing: Time for change?

Dr Martin O`Neill discusses the recommendations of a recent review of policing in England and Wales. A conference will be held on campus on 13 and 14 September to consider how meaningful change can be achieved in line with the report and also marks 25 years of policing provision at Canterbury Christ Church University.

(Un)trustworthy organisations? Implications of the Sarah Everard murder case

Dr Chris Beighton and Zahra Kemiche look at the issue of transparency and trust within organisations.

How to succeed with a policing degree apprenticeship

Christ Church is one of four universities working together as part of the Police Education Consortium, which is delivering the Police Constable Degree Apprenticeship programme with three forces: Surrey and […]

Policing and mixed messages in the media

Dr Emma Williams takes a look at how policing is portrayed in the media.

Terrorism and cyber hate

Dr Elaine Brown, Senior Lecturer in Counter Terrorism, discusses tackling cyberbullying in relation to the recent terror attacks.

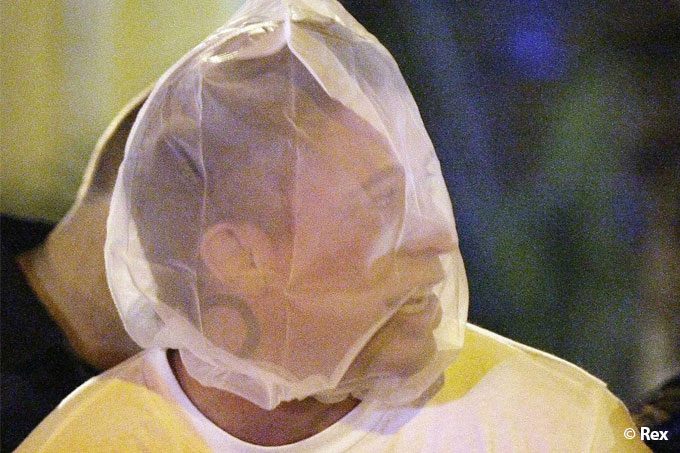

Are spit hoods too oppressive to be legitimate in a country like ours?

Graham Hooper, Principal Lecturer in the School of Law, Criminal Justice and Policing, challenges the increasing number of police forces in the UK calling for the use of spit hoods.