Having caught up with Dr Claire Bartram, as Co-Director of the Centre, and Dr Diane Heath, the Centre’s Research Fellow, I thought I would report on their involvement with the forthcoming Medieval Pageant on Saturday 4 July (the closest Saturday to the Translation of St Thomas on 7 July), which this year will be a virtual experience: https://www.canterburybid.co.uk/canterbury-medieval-pageant/ . Working with the Medieval Pageant team, Claire has been liaising between them and the Creative Writing staff and students at CCCU on some short creative pieces that relate to Thomas Becket.

Normally, of course, the Centre had a physical presence in one of Canterbury historic spaces – we started at the Canterbury Castle grounds, moved to the Franciscan Gardens and last year were in St Paul’s church, again with Annie Partridge of Canterbury Archaeological Trust. However, for this year we will be providing our child-friendly activities as a virtual offering, and Diane is (re)creating her edible medieval animal tile designing activity which I’ll be posting on the blog next week. As many regular readers will remember, Diane has had great success with this and allied activities in the past, and we will feature some of the photos of the best ‘tiles’ that are sent in. For who can forget the 2-headed hamster design: https://blogs.canterbury.ac.uk/kenthistory/shields-at-the-ready-the-dering-roll-and-medieval-education-day/ that was created in 2018 at the Education Day for local primary schools involving the Centre and organised by The Canterbury Tales visitor attraction (sadly now closed).

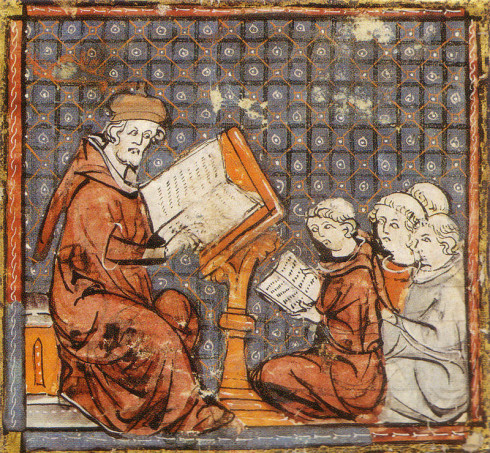

Keeping with the idea of schools and parents’ responses to sending their children back to school so that they don’t fall behind their peer group, I thought this week I would see what evidence there is for late medieval parents’ attitudes towards schooling. Most studies concerning education and schools in medieval and Tudor England quite rightly explore issues such as where and what sort of schools were available, the role of chantry colleges and chantry priests more broadly, what we know about the curriculum, and what happened respecting the foundation of new schools as a result of the Reformation. Dr Gillian Draper, Visiting Research Fellow at the Centre, has examined several of these issues in such publications as Kent Archaeological Society’s Archaeologia Cantiana and Pieties in Transition, edited by R. Lutton and E. Salter (2007). However, I want to take another angle and, yes, I’m going back to wills as one of the very few ways of gaining any sort of notion of ‘voice’ from those below the elite in late medieval society. I appreciate that there are always caveats when using wills; nevertheless, I am going to ‘cherry pick’ some examples to answer some questions.

To begin – whom did will-makers want to help in terms of receiving schooling? By far and away the majority favoured sons, seemingly especially younger sons, as in the case of Thomas Mershe of Walmer (1512), who expected his youngest son would in exchange pray for his father’s soul. Furthermore, sometimes testators sought to aid more than one son in this way. For example, John Bullyng (1482), Thomas Propchaunt (1493) and John Rand (1498) all from parishes in and around Canterbury, each wanted schooling for two sons. Stepsons weren’t forgotten either, as in the case of William Lyderer of St John’s in Thanet who sought to provide for Stephen in 1474. Nephews, too, might similarly benefit, although for Elwise Grawnger from Canterbury (1500) it was John, her first husband’s nephew, who was to attend school. Equally, godsons were seen as suitable recipients, for example William Stephen (1477), the rector at St Mildred’s in Canterbury, left a silver spoon and 6s 8d provided his godson William Baker became a scholar at Oxford University. While in the case of Thomas Walton (1508) of Hythe, Henry Baker may have been the son of one of his friends or neighbours. Schooling might also be seen as a gift to a poor boy. John Darell (1496) intended provision should be made whereby a good boy would go to grammar school, his progress to be monitored by Darell’s executors; and James Cursume (1518), a priest at the Black Prince’s Chantry, expected that in return for property in Kent, the College of Corpus Christi and Our Lady at Cambridge would provide maintenance for poor scholars.

How long did will-makers expect these boys would be at school? Often there is little information but Elwise Grawnger intended young John to start school at the age of 7 years, while Thomas Ramsey (1495), also from Canterbury, thought that five years (John was part way through the first of these) would be a suitable time for his son to be at school. George Davye of St John’s, Thanet, intended his son should stay at school until he was 21 years old and Clement Holway (1516) of Hythe expected his son to stay even longer – until he was 24. Whether these fathers had in mind time at university is unclear, but this was definitely the scenario Henry Gosebourne of Canterbury envisaged when he stipulated that 100s per year for 8 years should be given to a ‘Kent born man’ who wished to become a secular priest at Oxford or Cambridge. The candidate nominated by the abbot at St Augustine’s.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Medieval_university#/media/File:Laurentius_de_Voltolina_001.jpg

How much did will-makers leave towards schooling? As you would expect that varied and some intended goods should be sold which makes it impossible to know. However, of those who mentioned sums of money the least was 6s8d, but costs would have varied, too, especially if maintenance had to be included. Although Anthony Johnson (1509) only noted that his executors would pay, he was keen that his son John should be delivered to his master Sir John Pesmeth, his (school)master, to be with him bed and board for 3 years to be kept daily to school. Also in Canterbury, Thomas Ramsey’s son’s schooling was expected to cost £5 3s 4d per year, which is reasonably close to the figure Henry Gosebourne had been thinking of, which may mean the £40 in the hands of the prior at St Gregory’s priory in Canterbury for the education of William Clyffton’s two sons William and Nicholas would have given each boy 4 years of schooling.

Whom did will-makers intend should oversee these arrangements? Most will-makers were men and the majority turned to their wife and/or executors to fulfil their instructions. However, some left detailed instructions to try to ensure all was well for their sons’ education. Nicholas Mett (1533) of Hythe stipulated that while she was a widow Alice his wife should keep John and William to their learning, but if she remarried each son was to receive £10 and Master Peter Lygham, doctor, would thereafter ensure they kept to their learning, receiving £10 for each boy. The local parish priest was similarly viewed as suitable for this role, Robert Cokeram (1508) of Lydd intended that Master John Fyshar would have the keeping of his son Peter, Fyshar taking the profit from the 40 acres bequeathed to Peter until he reached the age of 20.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Medieval_university#/media/File:Philo_mediev.jpg

What did will-makers want beneficiaries to learn? Other churchmen might also be involved, and Ingram Jekyn of Alkham (1527) will’s is one of the very few that offers any indication of what was taught because he expected Sir Thomas Hewt, a canon, would teach Henry his son to read and write in both English and Latin. Later in the century numeracy is similarly mentioned by will-makers, but it seems unlikely this was a new development. The growing importance of boys’ choirs, firstly at religious houses, as at the almonry choir school at Christ Church priory, and probably similarly at the almonry at St Augustine’s abbey, had become a feature at some parish churches by early Tudor times. Among these was St Clement’s in Sandwich, Henry Pyham stipulating that 5s from the rent of a tenement should be given to the parish clerk so that teach the boys pricksong each week, as well as undertaking other duties.

How else might will-makers help? Will-makers gave a wide range of bequests to those they wished would attend school. Nevertheless, some gifts may relate more directly to this provision of schooling and of these books are probably the closest linked. In broad terms there are relatively few books mentioned in late medieval Kent wills, and the majority can be characterised as liturgical or theological, nearly always given by a cleric. Yet this is not the complete story and the local priest at Sholden, Sir Richard Wright (1527) gave his godson Richard two books of ‘phisyk’, a featherbed and bedding; while John Bayle (1496), the rector at Fordwich, aided his nephew through the gift of 3 books including a herbal. John Rand of Canterbury was presumably keen that his 2 sons would remember his gifts, in addition to their schooling, both boys received a mazer and 6 silver spoons, Nicholas’ mazer having a decoration featuring ‘Esterissh’ feathers.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Middle_Ages#/media/File:Studying_astronomy_and_geometry.jpg

What about schooling for girls? As you have probably noticed, all the beneficiaries (and most of the will-makers) have been male, and this is no accident. Schooling was viewed as valuable in lay society, but as we have seen it opened the door to entering the Church, and the Inns of Court can be seen as functioning as an alternative to a university education at Oxford and Cambridge, and a career within the legal profession, none of which were open to women. As an alternative, will-makers might help their sons and others to commence or complete apprenticeships. Yet again this overwhelmingly involved boys, the sole exception I have for a father aiding his daughter accordingly during this period is Edmund Hogan (1498) of Lydd. He bequeathed £10 to Alice’s master and mistress for her use at their charge and cost while maintaining and teaching her the craft of ‘shypstre’ (seamstress). Otherwise, daughters seem generally to have been expected to learn from their mothers or while in life-cycle servanthood, fathers or masters, as will-makers, providing dowries in the expectation of marriage. But there are a few exceptions, such as William Gybbe (1527) of Hythe who provided £10 for his daughter Margaret to join a Sandwich hospital or some other ‘honest’ hospital, and it is conceivable that those seen as especially able may have received some instruction comparable to schooling.

And to end on an even brighter note, the list of Canterbury and Kent online resources provided by us at the Centre has been added to MEMS Lib: https://www.memslib.co.uk/medievalcanterburykent so many thanks to Roisin Astell for her work on this at the University of Kent, and to Dr David Rundle for the initial suggestion.

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 1223

1223