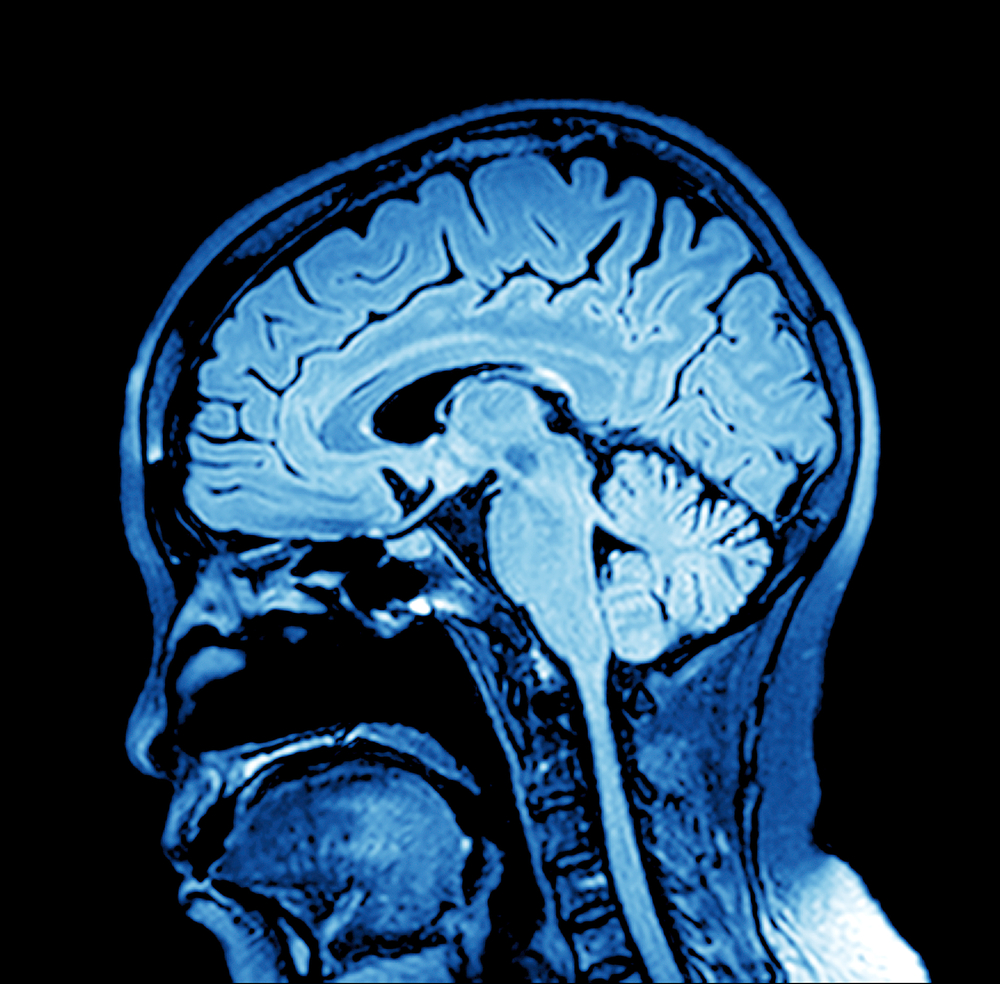

This Saturday marks ‘World Encephalitis Day’ raising awareness of syndromes caused by brain inflammation, but as Joel Petch, Senior Lecturer in Mental Health and Bioscience at Christ Church and Dan W Joyce, Research fellow from the University of Oxford discuss, some cases may be misdiagnosed as a form of schizophrenia, not encephalitis and this has the potential to delay the correct treatment.

Encephalitis can emerge from infection or dysregulated immune system responses and while recovery is possible, it is often a long process and requires a comprehensive multi-disciplinary response from healthcare.

Over the past decade, one form of encephalitis referred to as anti-N-Methyl-D-Aspartate receptor encephalitis [NMDAr encephalitis], has been the focus of increased attention.

The cognitive and behavioural syndrome arising from NMDAr encephalitis can be difficult to differentiate from that of psychosis. Common features include confusion, subtle or marked changes in behaviour, seizures, hallucinations, and disturbed sleep. It is accepted that assessment of these features alone may not result in the correct diagnosis given the overlap of features between NMDAr encephalitis and acute psychosis.

NMDAr encephalitis is caused by autoantibodies disrupting the function of NMDA receptors within the brain. These receptors are widely distributed throughout the brain- as are its ligands, the neurotransmitters glutamate and glycine. Correct functioning of NMDA receptors is critical in learning and memory, as well as playing a hypothesised role in social cognition, motor function, and perception. The ubiquity of NMDA receptors in healthy brain function is revealed by the effect of pharmacological blockage: the anaesthetic ketamine acts by blocking the NMDA receptor and can result in memory loss, sedation, and can cause agitation and hallucinations. This has led to an increased focus on the role of NMDA receptors and the glutamatergic system being implicated in psychosis

Psychosis can be loosely defined as a detachment from reality, characterized by reality distortion and a loss of functioning; often including hallucinations and the development of false belief systems. This syndrome, if recurrent or prolonged, can lead to the chronic relapsing/remitting condition, schizophrenia. The signs and symptoms of psychosis can be managed using antipsychotic medications combined with psychological interventions and social rehabilitation that enhance an individual’s ability to recover and/or manage these symptoms moving forward. These interventions are almost exclusively offered within specialist mental health services; commonly residing outside of mainstream healthcare facilitates. This division of healthcare services into ‘mind’ and ‘body’, is arguably based upon [and represents] the anachronistic notion of Cartesian dualism; and may cause more problems than it solves.

Since the discovery of NMDAr encephalitis in 2007, many further forms of autoimmune encephalitides have now been identified. This poses significant questions related to how best healthcare services can treat these previously unknown disorders.

If, as is the case with those experiencing NMDAr encephalitis, a person presents with a psychotic syndrome, much of the treatment would be in environments quite divorced from general healthcare. Further, there is a suggestion that some experiencing psychosis or with a historical diagnosis of schizophrenia – may have an autoimmune component to their disorder, which is entirely plausible. Insistence on healthcare facilities for the treatment of the “mind” – separate from those for treating the “body” – fails to acknowledge that a syndrome may have many causes and that investigation, diagnosis, and treatment might span several specialities.

Whilst autoimmune psychosis may be difficult to differentiate from non-autoimmune psychosis, a position paper published in The Lancet Psychiatry outlined an international consensus for the diagnosis of autoimmune psychosis and another paper identified the psychopathology of NMDAr antibody psychosis where agitation, hallucinations, delusions, and mood instability were prominent.

Management of autoimmune psychosis consists of peripheral blood testing and a lumbar puncture for cerebrospinal fluid [to confirm diagnosis]; imaging, along with immunotherapy or plasma exchange. However – many of those who present with psychosis are often signposted directly to mental health services which do not routinely have access to lumbar puncture, comprehensive imaging, or facility to deliver infusion therapies or plasma exchange. This has the potential to lead to delays in providing treatment, as well as the potential for misdiagnosis and mismanagement. This division of healthcare services reflects an ongoing separation of mind and body inherited from 17th century Cartesianism which now more than ever, might be better dismissed for the benefit of us all.

Joel Petch is a Senior Lecturer in Mental Health and Bioscience within the Faculty of Health and Wellbeing. Joel’s clinical interests include the interface between physical and mental ill-health, psychoneuroimmunology, psychopharmacology, and structural neuroimaging. Joel can be found discussing most things neuro-related on Twitter @joelpetch.

Dan W Joyce is a Consultant Psychiatrist in Early Intervention for Psychosis at Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust and a Senior Clinical Research Fellow at the Department of Psychiatry, University of Oxford and NIHR Oxford Health Biomedical Research Center.

Expert comment

Expert comment Emma Grafton-Williams

Emma Grafton-Williams 2334

2334