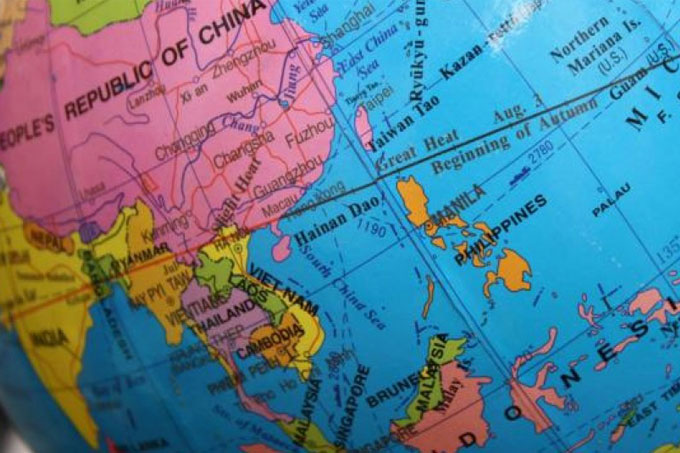

Professor of Geography, Peter Vujakovic, explains the powerful influence of maps in the escalating situation in the South China Sea.

The saying ‘the map is the territory’ makes sense in a world in which formal cartography has played a crucial role in determining geopolitical space.

The very act of drawing a line on a map has resulted in the annexation of large areas of the globe by former empires, the division of nations, or in the creation of new states.

There is a long history of cartographic justification for territorial and maritime ambitions, and this is central to the ongoing dispute in the South China Sea (SCS) and the recent decision by an international tribunal, the Permanent Court of Arbitration, that China’s wider claims to the sea have no basis.

The so-called ‘Nine-Dash Line’ map advocated by China since 1947 (originally published by the nationalist government, and then adopted by the People’s Republic from 1949) clearly denotes its ‘interests’ over most of the SCS.

The tribunal, however, has categorically stated that “there was no evidence that China had historically exercised exclusive control over the waters or their resources […and…] that there was no legal basis for China to claim historic rights to resources within the sea areas falling within the ‘nine-dash line’“.

China denies the finding has any legal basis and it has now been reported that China has asserted its right to establish an air defence zone over the area it claims.

The exact meaning of the dashed-line is unclear and the US Department of State has previously noted that “China has not clarified through legislation, proclamation or other official statements the legal basis or nature of its claims associated with the dashed-line map”.

The line is also not fixed, in fact it originally included eleven dashes, but two were removed following a maritime agreement with Vietnam, and recently an extra tenth-dash has been added to the east of Taiwan. This ambiguity is seen by many commentators as deliberate, as it allows China room for manoeuvre in its dealing with other maritime states within the region.

The dashed-line, however, does clearly signify some form of Chinese interest in nearly the whole of the SCS; it is even shown in Chinese passports and Chinese citizens take cruises to the disputed islands as a display of national pride.

China is in dispute with several states, including the Philippines and Vietnam, over key island groups and the access to marine resources that these might provide under international law. It was an application by the Philippines with respect to historic rights and maritime entitlements that led to the current judgement. China and other states have occupied various strategic sites, and China in particular has been involved in ‘island building’ activities, literally dredging sand to build reefs into permanent islands and adding airstrips and other infrastructure to confirm and ensure sovereignty. The key question is: what is China seeking by its assertive approach?

Many commentators see the ongoing disputes and China’s assertiveness simply in terms of its ambition to control the physical resources of the region: oil, fish and transport routes. Others, however, see the issue as more nuanced, involving not just marine rights, but reflecting China’s determination to assert its identity as both an ancient civilisation and a modern world power. This may in part be driven by negative factors – China’s ‘ontological insecurity’ – the need to secure its national and global self-identity; partly driven by the legacy of a century of humiliation due to Western and Japanese intervention and imperialism between the 1830s and 1949, and partly in response to the recent US ‘pivot to Asia’.

The involvement of the US is particularly important. For China the balance of power and operational freedom in the SCS for defence purposes may well be a key and understandable motivation, while for the US, China’s assertive campaign is regarded as part of its militarisation of the region.

The Chinese have a long memory and it would be foolish to see their assertive approach in the SCS as simply motivated by a hunger for oil and other resources, which they might more easily assuage through negotiation and regional cooperation. While no one should condone aggressive forms of geopolitics in the modern world, we do have to try to appreciate what truly motivates the words and actions of others if we are to live in a world of peaceful cooperation.

The issue also reminds us of the power of maps. The continued representation of the dashed-line in the news media, often in red in Western news providers to signify danger, also continues to reinforce China’s claim on a global stage and feeds a phenomenon known as ‘cartographic precedent’, helping to create a geographic ‘reality’ in advance of that reality.

Professor Vujakovic is the Associate Editor and former Editor of the Cartographic Journal and contributing author to the Times Comprehensive Atlas of the World.

To find out more about studying Geography at Canterbury Christ Church University visit the School of Human and Life Sciences.

Expert comment

Expert comment Jeanette Earl

Jeanette Earl 1636

1636