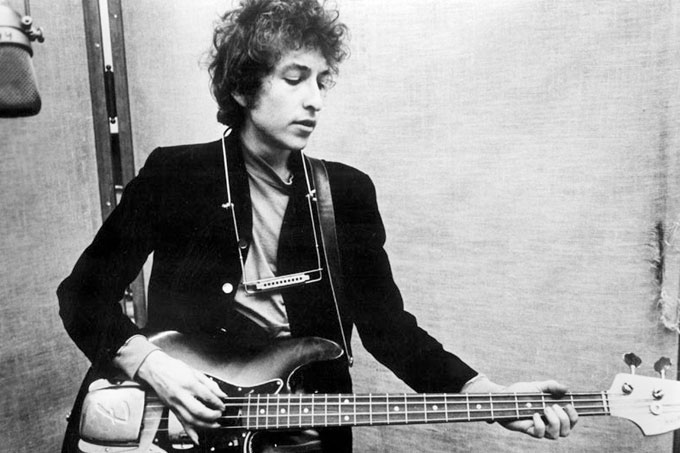

Dr Gavan Lennon, Lecturer in American Literature and Culture, reflects on Bob Dylan’s cultural and political importance.

The decision to award Bob Dylan the Nobel Prize for Literature is a momentous one. It not only affirms the literary value of songwriting as a form but it also reaffirms Alfred Nobel’s conviction that literature can be a weapon of peace.

My own research focusses on how literary form (usually the novel or the more conventional types of poetry) can make a social and political statement. Dylan was one of the first writers to help me realize that beautifully crafted writing could make and important political statement not in spite of its aesthetic qualities but because of them.

When Alfred Nobel, the chemist who invented dynamite, read his own premature obituary he was startled by the idea that he would be remembered for violence and war. In order to save his reputation, he invested his considerable wealth in a series of Prizes that would celebrate the efforts of men, women, and organisations who had committed themselves to fostering peace instead of war.

In his earliest albums, Bob Dylan (1962), The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan (1962), and The Times They Are A-Changin’ (1963), Dylan was already showcasing his skills as a literary artist. Adopting and adapting the traditional, early-modern ballads first collected by Francis James Child in songs as political as “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall,” and as lyrical as “Boots of Spanish Leather.” The literary innovations in these albums were not merely about taking existing literary traditions, but about forging a new type of literary expression, the twentieth-century popular song.

It was during this period, too, that Dylan’s commitment to racial and social justice was most visible. In 1963, Dylan and Joan Baez sang on the same stage and to the same crowd to which (fellow Nobel Laureate) Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. addressed his “I Have a Dream” speech during the March and Washington for Jobs and Freedom.

Dylan’s literary innovations were never divorced from his political convictions and he has continued to develop new and exciting ways of addressing America’s racial neuroses as well as celebrating its rich musical history at the turn of the 21st century in songs including “Blind Willie McTell,” recorded in 1997, and “Early Roman Kings” from 2012 as well as many others.

When Winston Churchill was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1953 it struck many as an odd choice. On the one hand, it would seem all too ironic to award the Peace Prize to the leader of a World War, but on the other it was a tacit acceptance of the literary merit of the forms of oratory and historical biography. The Nobel Committee effectively added these more political forms of writing into the literary canon. With their celebration of Dylan, the Committee is similarly acknowledging the new and developing form of the popular song. Dylan is recognized today not simply as a poet, but as a songwriter and a cultural activist.

I have long bored friends, family, and unfortunate interlopers with my argument that Bob Dylan and the Nobel Prize for Literature were made for each other. I am thrilled and gratified that I can stop.

Find out more about studying American Studies at Christ Church.

Expert comment

Expert comment Jeanette Earl

Jeanette Earl 1605

1605