We are now just over a month away from the online Tudors and Stuarts 2021 History Weekend on Saturday 27th and Sunday 28th March, which is extremely exciting. We are looking forward to welcoming virtually such a fantastic group of speakers who will be covering some fascinating topics, including Alec Ryrie on just how the Tudors cemented their new Church, Amy Blakeway on that explosive relationship between Queen Elizabeth I and her cousin Mary Queen of Scots, and Onyeka Nubia’s exploration of the black presence in Tudor England. Please to check out these talks and all the others at https://www.canterbury.ac.uk/tudors-stuarts and come and join us for what promises to be a brilliant and stimulating weekend. All things being well, I’ll be doing a piece on KMTV next Wednesday on the Weekend, please do look out for this.

Regarding events over the last week, I thought I would report that Dr Diane Heath and Penny Bernard have submitted their preliminary grant proposal on ‘Medieval Animals’ to the HLF and should hear next week, I believe, regarding whether they can submit a full application. In other news, I have held a palaeography workshop for the Lossenham project, with a second later this week, by way of an experiment to see how such online events might work. So far things look promising and if there is greater demand, more will take place. I will also be catching up with the Lossenham project wills group shortly to see if the sub-group has decided on the best way forward using a spreadsheet system to record details. In addition, tomorrow evening Dr Gillian Draper, a Visiting Research Fellow at the Centre, will be speaking at a BALH online history meeting on Jack Cade’s Rebellion and the Battle of Solefields. I’ll be providing the introductory presentation in what promises to be a very interesting evening.

For this week’s blog, my main report is on Anna-Nadine Pike’s fascinating lecture last week, which formed the last in the series of the Centre’s Lunch Time Lectures in association with the Friends of Canterbury Cathedral and the Canterbury Association of Medieval and Early Modern Studies (CAMEMS) with Kent MEMS. Anna is a Graduate Trainee in the Library of New College, Oxford, and for her presentation she drew on her MA dissertation completed last year at the University of Kent.

Anna opened her talk by asking her almost 50 strong audience to focus on two textiles – linen and wool, and to imagine just what these fabrics would feel like. For she wanted to highlight how when the Bridgettine nuns read about these fabrics in the devotional works of their leader, they responded emotionally to the works and the fabrics, because it was these same fabrics that they would have been wearing. This inter-relationship between text and textile is at the heart of Anna’s research as she explores how this aided the nuns’ prayer and meditation as they sought to know Christ through the self. The engagement of the five senses is key here, and for her presentation Anna had decided to focus on touch in her assessment of the role and value placed on affective piety, especially in terms of Christ and his mother.

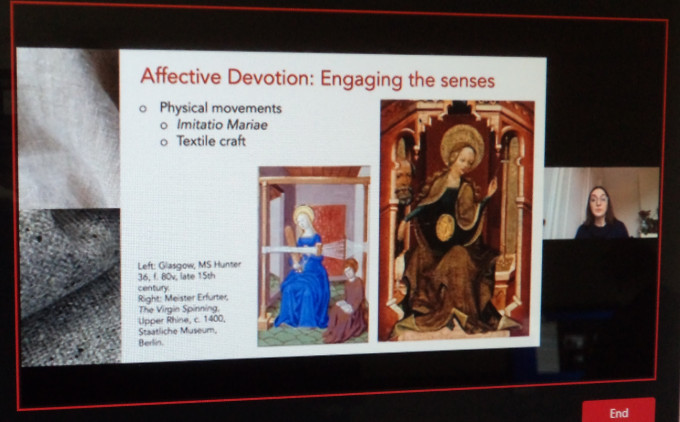

Although not an exclusively late medieval development, affective devotion, that is an emotional response became increasingly ‘popular’ in the late Middle Ages, both among the laity and those who had entered a religious house. The goal was to know Christ through an imaginative union with him by seeking to use sensory perceptions about emotionally charged events in his life and passion. In this way the person could enter into the story – see The Book of Margery Kempe for an extreme layperson’s involvement, through their senses being fully engaged. Nor was such emotive imagining confined to Christ because the Virgin Mary, especially through her relationship with Christ, was seen as equally important. For example, thinking of the Pieta where Mary is depicted in sorrow holding Christ’s broken body after the Crucifixion on her knee, just as she had held the infant Christ at the Nativity.

To provide a guided reading of such episodes the 14th-century Meditationes vitae Christi was increasingly used, and this bringing of words and images together could be taken a stage further as believers through their physical movements and actions imitated those of Mary – they too were at the foot of the cross, for example. Additionally, the idea of the Virgin Mary as spinner or weaver was another important motif that the believer could tap into, such work becoming a meditative act in itself.

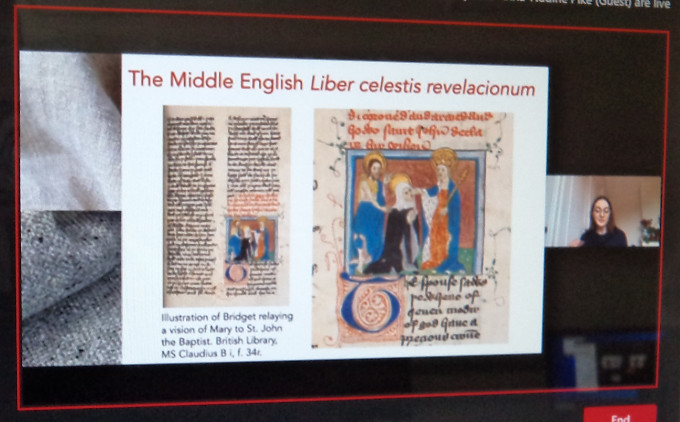

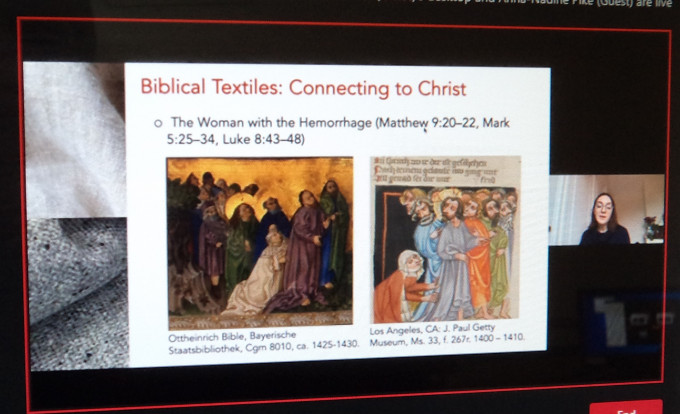

With this as background, Anna then introduced St Bridget of Sweden, a 14th-century mystic whose divine revelations were written up in Latin texts which contain numerous references to textiles and their symbolism. She was also responsible for the establishing of an order, primarily of nuns, and one of these religious houses was founded in England at Syon Abbey. As you might have expected these houses were dedicated to the Virgin Mary and Bridget’s divine revelations were translated into Middle English of which four survive. Regarding Anna’s discussion on the value placed on touch, these texts draw on the idea of communication being transmitted through the touching of fabric, that is clothing that in turn touches the body of the wearer, the fabric acting as a conduit. Perhaps the most famous example of this is the veil of Veronica, where divinity was seen as being woven into the fabric’s texture.

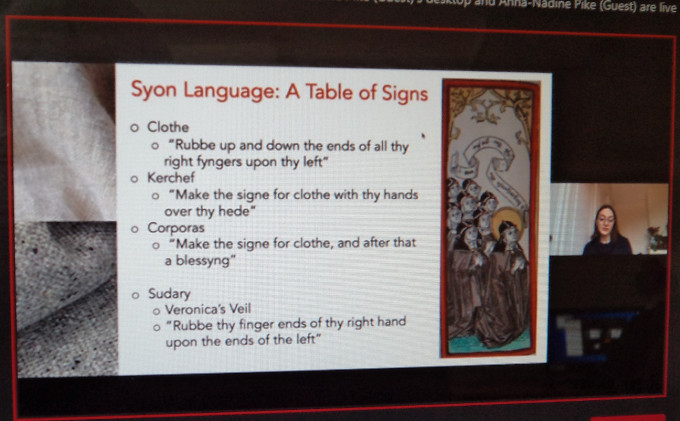

For Anna, ‘A Table of Signs’ is especially evocative of this importance of fabric because such signs were used by the nuns during periods of silence and among these signs are several for fabric, the signs involving the sense of ‘feeling the fabric’ against the skin, although the sign is actually skin on skin – finger on thumb. Therefore, through the signing the nuns were deploying the idea of the feel of the fabric on the body and denoting where it would be worn – the veil on the head. To further such ideas, the order decreed that the clothes and fabrics to be worn by the nuns should echo those of St Bridget, which means that as she had spoken of fabrics in her revelations, her nuns would experience these same fabrics and garments in their mirroring of her. Among her writings she highlighted three fabrics, wool, linen and silk. Taking linen symbolically, for example, she drew on the notion that it is soft and gentle and the more it is washed the cleaner it becomes, and thus denotes peace and concord. For the sisters, they became attuned to such ideas, their clothing becoming a meaning of imagining Christ and his mother, and their suffering. Moreover, this would have been in evidence from the time of the reclothing ceremony when the new nun put on the clothes of Bridget and caste off those of her earlier life.

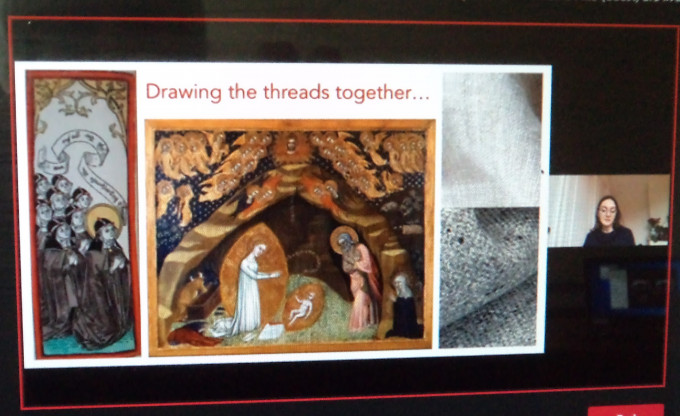

Moving to a Bodleian manuscript that may have been at Syon, Anna discussed a prose life of Mary that was stitched together from references to Mary across St Bridget’s ‘Revelations’, a carefully produced text that often takes single sentences rather than whole chunks of texts to weave this narrative. For her talk, Anna was keen to demonstrate how this narrative uses ideas about fabric, and again these fabrics are wool and linen. For example, Mary wears a kirtle of fine linen, its simplicity echoing both the clothing of Bridget and her nuns. Equally colour comes into play here because being white, rather than the traditional blue, Mary’s mantle, like that of the nuns, symbolically evokes the notion of spiritual poverty. While Mary’s actions of swaddling the infant Christ in bands of linen and wool evoked emotional responses as the nuns meditated on Christ’s Nativity (and Passion), and his mother’s role as intercessor between Christ and the Bridgettine nuns.

Drawing her presentation to a conclusion, Anna reiterated how these approaches gave the nuns the means to draw on their senses to meditate on these biblical episodes, their emotional response triggered through the sense of touch of skin on fabric, as well as through working to produce these same fabrics. Such an excellent lecture brought a flurry of thoughtful questions which Anna answered, and it was also great to see comments coming in such as ‘a really excellent talk’ and ‘thanks for such a perceptive presentation’. And it was brilliant to round off this series in this way, and I just want to say many thanks to all six of our speakers, as well as to Diane Heath for acting as the producer throughout and to Toby Charlton-Taylor for his invaluable IT support.

Moving to my second report on a presentation this week, today was a meeting of the Kent History Postgraduates. Nearly everyone was there again, one of the few exceptions being Dr Lily Hawker-Yates who was on the road from Manchester to Aylesbury to take up a 6th-month full-time post on a community archaeology and public engagement project – very exciting and good luck Lily. I thought I would also just mention that as co-organiser, Dean Irwin’s 2-day conference last week on the medieval Jews of England was a great success – well done Dean!

Today’s presentation was given by Tracey Dessoy, drawing on her chapter on women and religious patronage among the knightly families of east Kent from the late 12th century to the later Middle Ages. Tracey specific focus is on noble women as donors, but obviously it is important to look at the family and gender differences, as well as generational differences and relationships. Although Tracey is very interested in the relationships displayed through religious patronage concerning the various monasteries and saints’ cults, she is also very keen to investigate the incidence and use of manorial chapels, in addition to links to the local parish churches. Even though she drew on more east Kent families, her main focus today was on a baronial family with Agnes de Cundy as her central figure, and the de Cornhill family, who were further down the social scale. In particular, she highlighted the activities of Matilda and her granddaughter, another Matilda who took the name de Lukedale, the site of the family’s chapel and chantry.

There is not sufficient space today to do full justice to Tracey’s richly detailed case studies, so I’m just going to touch on a few issues, and suffice to say this thesis chapter is progressing very well as Tracey sees shared motifs and concerns between the baronial families of the late 12th and early 13th century, and what might be seen as the next generations among the knightly families from the mid 13th century onwards. Furthermore, it is also a matter of examining where certain family members didn’t deploy their religious patronage as much as where they did. For example, Agnes de Cundy who married into the up and coming aristocratic de Clifford family whose area of interest was the Welsh Marches, and whose own family were important landholders in Lincolnshire and Nottinghamshire, seemingly to a considerable degree (but not entirely) ignored both families’ interests in the religious institutions of Lincoln and Clifford in the Marches. Instead, she looked to her Kent landholdings in the form of the manor of Wickham and sought burial at Canterbury Cathedral, providing lands to the value of 100s for this privilege, with 40s worth to St Augustine’s abbey, 20s worth to St Gregory’s priory and similarly to St Sepulchre’s nunnery. She also remembered her parish church in Wickham, intending that it should receive an aisle with an altar dedicated to All Saints, where masses for her soul would be celebrated.

As Tracey discussed such grants may be seen against the backdrop of the growing importance of Becket’s cult, and the giving of lands and rents to the shrine, as well as developments taking place in the parochial system, the provision of parish religion, and directives regarding how the church building should be maintained. Moreover, for the knightly families that held rural and urban holdings, these offered the means to support intercessory concerns, not only for individual family members but for their ancestors and descendants. To explore these ideas, Tracey is deploying her east Kent case studies in context, drawing on examples from the secondary literature to see how far Kent families, and especially women, followed these broader trends.

Moving on from this, Tracey explained how household chapels as part of the manorial complex were especially favoured by her east Kent families, and she has a cluster of these manorial chapels in the Littlebourne area. Furthermore, as in the case of the de Cornhill family, their provision was to a degree linked to familial relationships with the local monasteries, in the de Cornhill case with St Augustine’s abbey. Again, Tracey has investigated how these chapels were also used as chantry chapels, and how such matters as the choice of the saintly dedications may be connected to contemporary events and concerns. In particular, she has explored Iffin chapel and its dedication to St Leonard.

Tracey beautifully detailed presentation provided a great basis for group discussion, not least because Jane, although looking at religious patronage in west Kent and generally in the later Middle Ages, could see interesting parallels. Other discussion centred on the documentary sources Tracey had been able to locate, as well as matters relating to mapping and how she was employing archaeology to enhance her analysis. And for this aspect, Lisa was able to provide a link to material on the Canterbury Archaeological Trust website that may offer more information. Thus once more the collaborate strength of the group was in evidence, and next week I hope to be able to report on the filming by Alex Durham of Paul Bennett’s ‘Early Tudor Canterbury’ for the Tudors and Stuarts History Weekend.

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 1604

1604