This week I’m playing catch up, and because there is so much, I’m going to save the last of the Lunch Time Lectures by Anna-Nadine Pike until next week (for the joining url, see last week’s blog). Moreover, even though I wasn’t able to get to it, apologies Dean, I just want to say that as co-organiser Dean’s online conference on Jews in medieval England has also taken place this week. Thus, the Centre for Kent History and Heritage is very active on all sorts of fronts.

To begin, I want to bring you the Kent History Postgraduates’ group catch-to meeting last Wednesday. However, before I go round the group, I thought it was well worth saying that everyone is now finding (and in some cases this has been the case for a while) that they are struggling to keep researching. For archives remain closed, and there are also issues concerning getting hold of older periodicals because the library does not subscribe to these early issues and whereas before they could be looked at the British Library, this is no longer an option. Consequently, they are working against a backdrop of adversity and while they appreciate this is not a life and death scenario, it does definitely hit morale.

I’ll start with Dean, and his time over the last few weeks has largely been taken up with conference matters. Although much of this relates to answering queries from those who have signed up, he has also written his paper. However, he had yet to finish preparing for the workshop on the second day covering the expulsion of the Jews under Edward I. They are doing this workshop to offer ideas to secondary school teachers about how they might teach this topic in response to concerns about the curriculum and the need for inclusivity in the light of recent cultural developments.

Next moving to Jane, she is working on PCC wills as one of the few available sources and, in particular, she is continuing her investigation of the Culpeper family who had considerable links to Bayham Abbey. Her special focus currently is disentangling the records of two Thomas Culpepers from the early 14th century. This is proving to be a rich seam respecting her investigation of Bayham and other religious houses in the area on the Kent/Sussex border.

Keeping with wills, Maureen is similarly looking at an area in west Kent, but her focus is the early modern period and another family of lawyers in Tonbridge. She is also working through the digital copies from Canterbury Cathedral Archives of the Tonbridge larderer’s accounts and rental, albeit they are not providing much new information.

Janet has similarly been on the TNA website, although for the Kent Manorial Register: https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/manor-search and her research has also taken her to the BL site where she has been looking at the images of drawings produced for the detailed 1st edition of the OS maps. Now Kent was one of the first counties surveyed and these drawings provide far more than the usual maps of the period. At the moment there are some issues about enlarging the images, Janet did provide the link at: http://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/onlineex/ordsurvdraw but it will be necessary to investigate this further, possibly by contacting IT at CCCU, as well as the BL because they sound to be a brilliant resource. Janet is also investigating Henry of Eastry’s memo. book, but more on that another time.

Pete, having been working very hard, is taking two weeks off, while Jacie has health issues that have hampered her research recently. Nevertheless, she will be in touch with the growing group of new interviewees and this looks to be a fruitful avenue. Lily, too, has been less busy of late, but she is making progress on her article although she is hampered by lack of access to certain older journal articles.

Tracey has volunteered to give the next presentation in a fortnight’s time and thus I’ll keep it brief here. She is continuing her assessment of female patronage and piety in east Kent and now feels that she understands the apparently contradictory records for Agnes de Condy. Furthermore, she feels she is making good progress concerning the relationship between various abbots at St Augustine’s and their senior officials.

Finally, Victoria is continuing to make excellent progress regarding the St Albans library inventory respecting the types and thus themes therein. She is making good headway about where and when the books were sold, but she, too, could do with access to the archives, specifically the Kent History Library Centre at Maidstone.

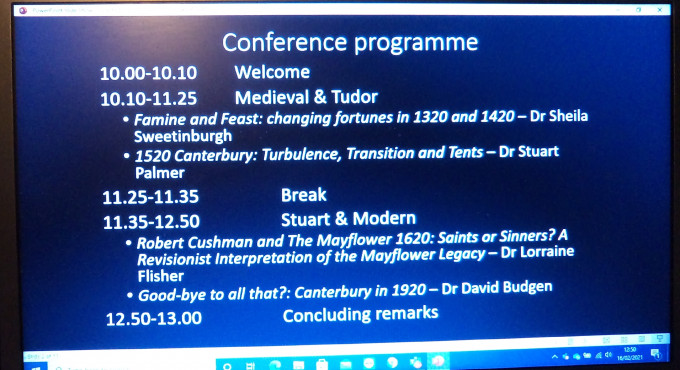

In some ways this was a theme of the conference hosted by the Centre for Canterbury Historical and Archaeological Society (CHAS) on Saturday because given the chance all the speakers would like to have had at least some time in the archives. Notwithstanding this issue, it was a brilliant conference and offered four complementary presentations on ‘Canterbury through the Centuries’. I’m afraid I won’t be able to do it justice but hopefully this will offer a flavour of what the eighty-strong audience enjoyed from the quality and variety of the questions posed to the speakers.

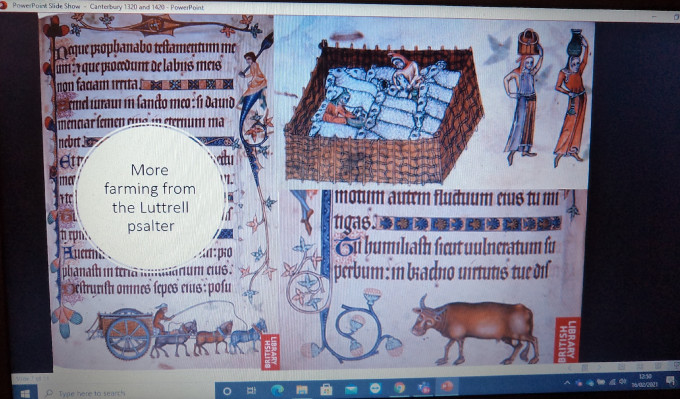

I kicked off the first session on ‘Medieval and Tudor‘ by looking at the lead-up to the Jubilees of St Thomas in 1320 and 1420 because on the face of it they look very similar in that on both occasions the shrine offerings for 1319/20 and 1419/20 brought in about £570. But they weren’t! For the second half of the 1310s was extremely difficult, albeit perhaps not as catastrophic in Kent as elsewhere in the country because of the manorial system commonly found in the county and the agrarian strategy deployed over much of Kent. One effect of the former was higher levels of migration between countryside and town, the Canterbury early freemen’s rolls offering evidence of this. While for the latter, in broad terms it was an intensive farming regime, including the heavy use of manure, marl and lime, the use of turn-wrest ploughs, and horses in preference to oxen, the use of legumes, which allowed continuous cropping, the growing of fodder crops and the production of hay, which meant livestock of all kinds could be over-wintered in stalls and sties, with specialist dairying within an integrated mixed farming strategy mainly based on cattle, but some sheep.

Thus, yes, the wheat crop was a disaster between 1315 and 1317, which brought large price increases due to scarcity, but barley and oats were less badly affected compared to the national picture. Notwithstanding this, what did hit Kent very badly was cattle plague in 1319 and 1320, perhaps wiping out half the herds, which was a hammer blow because of the underlying regime in Kent. Such a scenario brought unrest among the peasantry, who were apparently well organised – we have some very interesting details from Thanet, and even though the evidence is limited this was probably widespread and had a knock-on effect in Canterbury. Consequently, even though the abbot at St Augustine’s was seemingly less than enthusiastic about the 1320 Jubilee, his new vineyard of far greater importance (allowing him to drive out a ‘nest of robbers’ in North Holmes Road), for those from Canterbury, Kent and further afield who came to Becket’s shrine that year, the saint may have offered one of the few rays of hope in an otherwise very bleak world.

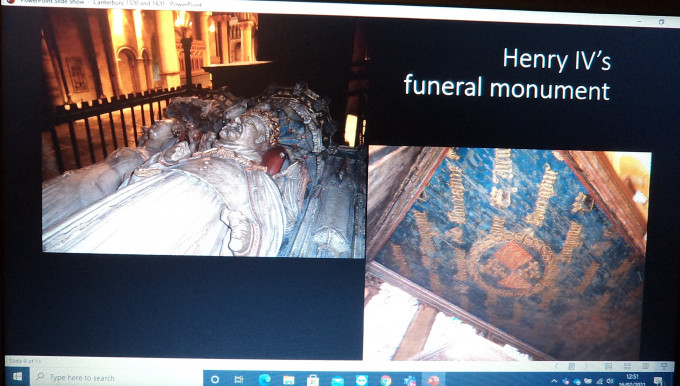

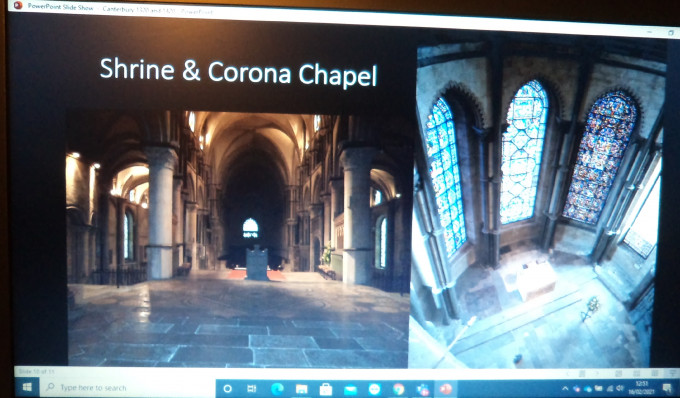

In contrast, the later 1410s had heralded a series of martial triumphs, and the king’s pilgrimage to Becket’s shrine soon after Agincourt and again in the company of the Holy Roman Emperor in August 1416, while 1420 itself brought Henry V’s wedding and the prospect of uniting the two crowns, and for the survivors of plague the economic prospects were generally rosy. Moreover, in Canterbury itself Christ Church Priory had been busy building at the cathedral and in the city – The Cheker and subsequently more inns, an idea enthusiastically taken up by the civic authorities. Thus city and cathedral looked forward expectantly to 1420, as well as embarking on policies – publicity and provisioning, to ensure pilgrims saw coming to the shrine as a ‘good thing’. Having described their various endeavours inside and outside the precincts, including indulgences, poems, letters and making sure there were plenty of victuals in the city and beds were similarly available, I drew attention to the developments that had and were taking place in the cathedral itself to heighten the ‘pilgrimage’ experience. Among these were the introduction of polyphonic choral singing, the growth in the number of chantry chapels, architectural changes, the sensory overload occasioned by the multiplicity of candles, incense, brightly coloured funeral monuments and the care of the shrine keepers, all intended at the same time to ensure that the increasingly complex liturgical life of the monastic community was not affected by the presence of pilgrims.

Yet, in many ways although 1420 was seen as a great success, things were about to go down hill quite rapidly and Canterbury was at times drawn into the later Wars of the Roses. Although by and large the city navigated the period successfully, there was one spectacular disaster in 1471, a warning if the civic authorities needed it that keeping royal favour remained vital, and, as the city moved into the Tudor dawn, this scenario of crown-town relations would be enacted again in 1520.

This brings me to Dr Stuart Palmer’s presentation. I expect some of you will remember Stuart whose doctorate explored Canterbury under the early Tudors and who is now in post at Sidney Sussex College in Cambridge. Stuart began by setting Canterbury in the context of other major English towns, for even though it was certainly not on a par with provincial centres such as Norwich and Bristol, it was the largest town in the south-east outside London. Moreover, as the home of the internationally important shrine of Becket, it was a cosmopolitan city, and its position between London and Dover (and Sandwich) meant that travellers, and thus goods, people and news were a feature of the city’s landscape.

Against this background, Stuart took the audience through an assessment of the events of 1520 at Canterbury, Dover and the Field of the Cloth of Gold near Calais involving the three most important monarchs in western Christendom – Henry VIII, his wife’s nephew Charles V the Holy Roman Emperor, and Francis I of France. For all three saw themselves as Renaissance monarchs and in the spring of 1520 their pursuit of peace fitted well with their humanist credentials, as well as providing a means for in a sense a bit of one upmanship.

In many ways these high-level meetings were a follow up to the Treaty of London made in 1518 that had been master minded by Cardinal Wolsey whereby the major states agreed a non-aggression pact and to help states that suffered attack. This initiative allowed Henry to play a central role and in 1520 this was to become a series of public spectacles, first through Henry’s meeting with Charles V and his provision of hospitality for the Holy Roman Emperor at Canterbury and then the glorious meeting across the Channel at what would become known as the Field of the Cloth of Gold between Henry and the king of France.

Thus, as Stuart explained, Henry went to meet Charles V at Dover to escort him to Canterbury for a time of lavish hospitality and entertainment, Charles also meeting his aunt, Henry’s queen. For the civic authorities at Canterbury, this was an opportunity to display their loyalty and to demonstrate their good governance of this royal city. The civic authorities, dressed in new scarlet gowns, met the royal party and in procession escorted them along the Dover Road, through St George’s gate and down to Christ Church gate at the Bullstake (Buttermarket) where the royal party dismounted and entered the cathedral precincts and into the cathedral to hear Mass. Moreover, because Henry was on his way to meet Francis all the baggage needed for the Field of the Cloth of God was also available for use during this meeting with Charles, making the occasion even grander than it would have been in more normal circumstances. Thus, the sheer scale of all this would have been tremendous, and a major economic bonus for the city that was beginning to struggle in that the cloth and iron industries had increasingly relocated to the Wealden towns.

In terms of where the royal party would stay, especially when they had travelled down from London, this was at a tented encampment in the Blean which was provided by the civic authorities, albeit once in the city hospitality might be provided by the archbishop, the prior at Christ Church or the abbot at St Augustine’s. Nor was such hospitality the only gift provided by the city because the arrival of such personages would be marked by gift-giving that might be in the form of luxury food, such as swan or porpoise, or drink in the form of beer or wine or silverware, such as a cup perhaps decorated with the city arms.

As Stuart pointed out such ceremonies and the demonstration of deference, as well as munificence were a vital part of crown-town relations, as witnessed by Canterbury’s impressive collection of royal charters. Furthermore, as a corporation, the authorities had long memories and 1520 provided an opportunity to have new copies made of its earlier charters. These cultural markers denoting the authorities’ good governance were similarly evident through a new post outside the guildhall for notices, the refurbishment of the cross at the Bullstake, and, as a measure, of the authorities’ role in law and order, the provision of a new cucking stool at the abbot’s mill. In addition, they repaired the Dover road, which might be seen as killing not just two but three birds with one stone: this section of the king’s highway was bordered by land claimed by St Augustine’s, partly through its daughter house of St Lawrence’s hospital, which was therefore derelict in its duty to maintain the road. As well as highlighting such poor ecclesiastical management, the city authorities were demonstrating their ‘generosity’ by putting right the abbey’s deficiency for the benefit of their overlord: the king, and thirdly it offered a way for the civic authorities yet again to stake a claim to what had been contested territory between abbey and city.

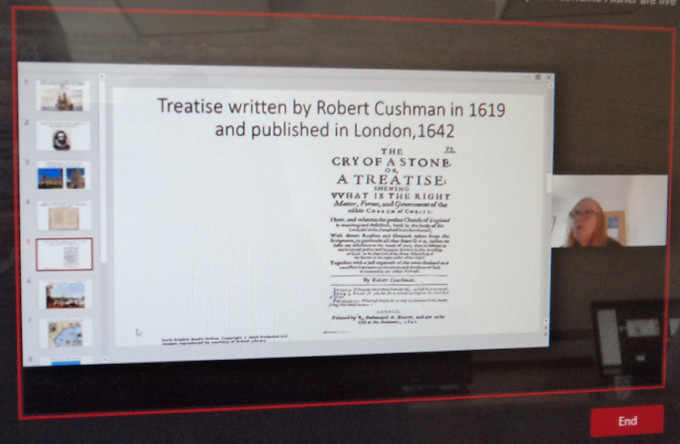

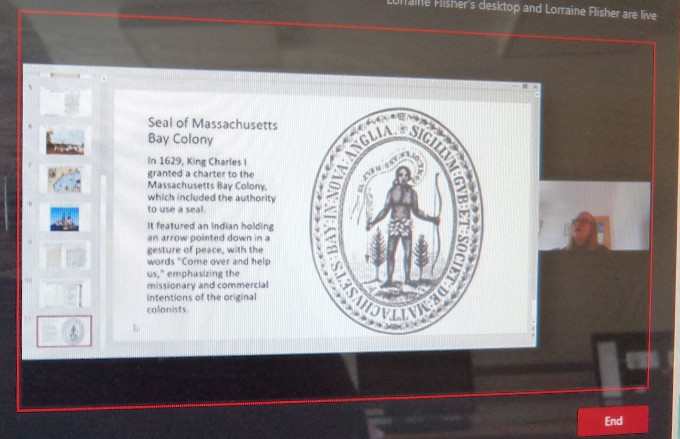

This session generated lots of questions and a good discussion about the role of public display in this ongoing relationship between the king and his city. And then after a short break Ann Chadwick began the second session on ‘Stuart and Modern Canterbury’ by introducing Dr Lorraine Flisher who took up the story by looking at 1620. Lorraine an Associate Lecturer at CCCU and an Associate Fellow of CKHH. She is interested in trans-Atlantic connections and Kent migration, radical religion and communities and their cultures, which meant she was extremely well placed to provide a re-assessment of Robert Cushman and The Mayflower legacy.

Lorraine began her presentation by highlighting the issues historians face concerning bias and the importance of understanding that history is not written in isolation but involves a dialogue between the present and the past. Although true of all history, this is especially pertinent currently in terms of America’s past from the time of the arrival of the early colonists in the early 17th century and exactly what is to be made of the idea of the ‘founding fathers’ of ‘God’s own country’. For what may have become a Day of Thanksgiving for some became a Day of Mourning for others, and this polarity of experience continues to colour the story and political rhetoric surrounding The Mayflower, in particular.

Against this backdrop, Lorraine introduced the audience to Robert Cushman, who had been born in Rolvenden in 1577 and who had as a young man been apprenticed to a Canterbury grocer. Whether it was his early life in the Weald that had shaped his puritan religious views is unknown but seems highly likely and he found himself in trouble with the authorities in Canterbury, spending a night in the Westgate jail. However, this did not stop him from completing his apprentice, becoming a freeman of the city, marrying and having a son, but as things became more difficult because of his religious views, he and his young family travelled to Leiden to join the community of religious exiles there. Seeing themselves as God’s chosen people, the pre-destined ‘saints’, this exclusive ‘community of the righteous’ were busy debating theology, printing books and engaging in trade and industry, especially the making of cloth. However, things became less secure, in part due to Leiden’s guild structure and so the community looked elsewhere.

Now it was not just these extreme Protestants who had their eyes on the ‘New World’, and as Lorraine explained London merchants as venture capitalists saw there was money to be made out of furs and cod. Two stock companies had been set up back in 1606, and as things developed there were ‘armchair’ share holders who were intending to stay in England and those who would effectively buy into the company by agreeing to work for it for part of the week, although this was later increased to all the week, bar the Sabbath. The ‘pilgrims’/settlers weren’t keen on this new condition, but Cushman had agreed the revised contract. It is reputed that he signed it in Canterbury but this could just as easily have happened in London. The point is either way the die was cast, and the plan was that The Speedwell from Holland would meet up with The Mayflower at Southampton. Not that things went to plan but finally sailing from Plymouth The Mayflower with its 102 passengers, a mix of separatists and ‘strangers’, did arrive in New England near Cape Cod in November 1620, although not where they had intended to land. Before disembarking the ‘pilgrims’ (settlers) agreed a system of self-government known as the Mayflower Compact – signed by the male members of the party.

The following year The Fortune arrived, but there were still tensions between the aims of the settlers and those of the merchant backers, who were looking for a return on their investment. For Cushman in all of this, we can gain an idea of his stance from his sermon delivered on the first Thanksgiving on 9 December 1621. Equally important was the viewpoint of the indigenous people, however, the metanarrative has played this down over the centuries, the Wampanoag seen as playing a bit part in this celebration of escape from religious persecution that for them brought nothing but death from disease, enslavement and the loss of their way of life, resources and tribal lands.

Cushman himself returned to England aboard The Fortune as it took back beaver skins and other commodities as payment by the settlers for their debt to their merchant backers. However, the goods were taken by pirates during the voyage, but he did make it back to England, dying in Benenden in 1625, his son Thomas having remained at the Plymouth colony.

American dream, the idea of God’s own country, that the ‘pilgrims’ were innocent victims of religious persecution who had journeyed to an empty land to establish the ‘promised land’ remains within the American psyche, witness the value placed on Thanksgiving. Moreover, this meeting of merchant capitalism and Protestantism still underpins American culture in many ways, and even though the ‘pilgrims’ sailed away, it is no accident that Cushman came back!

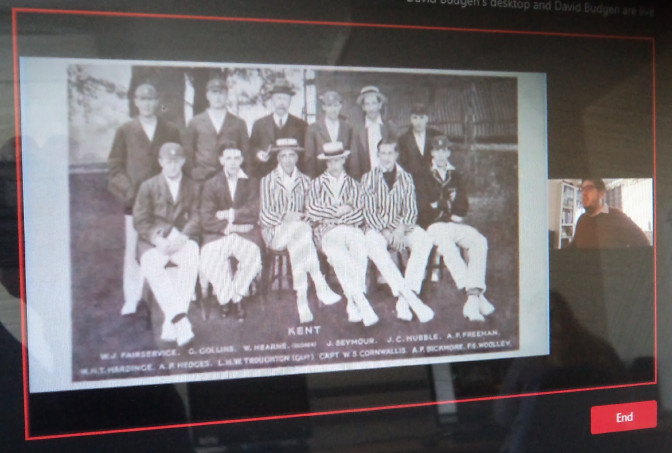

Moving on three centuries to the year of the foundation of Canterbury Archaeological Society, Ann introduced the morning’s final speaker Dr David Budgen, a 20th-century cultural historian who lectures in American Studies at CCCU. David began his presentation by highlighting what he sees as a tension that was present in this post-WWI period where there was a strong desire to commemorate and memorialise the ‘glorious dead’ but at the same time there was a need and a desire for the survivors to move forwards, which required a re-adjustment to civilian life and the changes that had taken place while they had been away. Moreover, unemployment was an issue and there was almost a feeling at times that the returning soldiers felt themselves strangers in their own land. Also, while war memorials and the like were welcomed, there was a feeling that at times such communal initiatives were in the hands of churchmen, local councils and landowners, not the communities from which the fallen had come. And there was a feeling of utilitarianism among some who wanted a memorial that benefitted the local community, such as a village hall or similar. For Canterbury, the idea of a bandstand in the Dane John Gardens was seen to fit such an aspiration, alongside the more traditional war memorials in the Buttermarket and elsewhere across the city, such as that for the East Kent Chamber of Agriculture at the Fountains Hotel. As David discussed, the value of naming all those who had been killed was viewed as paramount, albeit the need to push on and set up the war memorial and then get the bronze plaques with the names done when funds became available was often the reality.

During this time of re-adjustment David also mentioned that many other matters were undertaken, including a desire to re-instate what had been lost. Consequently, Bekesbourne aerodrome was de-commissioned and released from RAF control to return to its former owner. Similarly, there was pressure to provide compensation as well as to return the grubbed-up hop fields to their traditional agricultural use, which was widely supported by the NFU. Nonetheless, things were not that rosy, and an outbreak of foot & mouth closed the markets at Canterbury and Ashford. Equally, there was a builders’ strike, and among their demands was a 44-hour week. Now some of these craftsmen must have been war veterans but they received limited sympathy. Other aspects of life also returned, and in a county famous for its cricket team, Kent was in need of a new fast bowler.

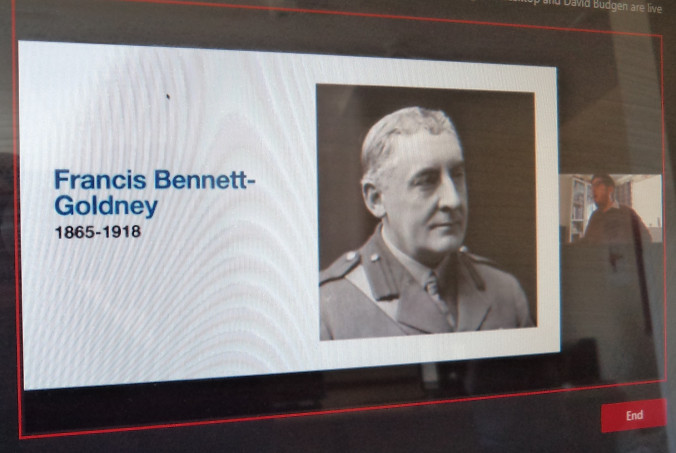

Having discussed these broader aspects of the role of war veterans and how they were being remembered, David turned briefly to the case of Canterbury’s Conservative MP who had been killed in 1918. Francis Bennett-Goldney had been a member of the establishment, having been MP from 1910 until his death, mayor six times and the owner of Abbots Barton. Although he had also been a controversial figure during his lifetime, his post-mortem reputation fits more comfortably within these rituals of remembrance as seen in contemporary reports in The Times. Nonetheless, as David highlighted, this post-mortem view hides his seeming ‘borrowing’ of books and other precious items from the city’s museum at the Beaney, such careless at the time in the subsequent judgment put down to the grey area he appears to have enjoyed as the Beaney’s Hon. Director and Librarian. Thus, as David concluded, such an individual provides in microcosm this tension, for like others he probably should not be seen as living up to ideals placed on those who died in war. For he was more than a name on a war memorial, and, just like those who came back, as an individual he was neither ‘saint’ nor ‘sinner’, borrowing from Lorraine’s talk, but somewhere in-between. Finally, and bringing these presentations full circle David reported that in 1920 The Chequer of Hope (as it had become) had been sold for £2,000.

After these excellent presentations, both answered a series of questions before Ann concluded by reminding the audience how the Society had begun, its early years and what it does today, including its first-class website and its series of winter lectures. She then thanked all the speakers again and the conference finished just before 1pm, which just leaves me to thank Dr Diane Heath for doing a sterling job as the producer and Toby Charlton-Taylor for giving up his Saturday to provide IT support.

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 2239

2239