This week I want to catch up with events involving History and the Centre over the last week, but will leave Dr Mark Hutchinson’s paper to the Staff-Postgraduate Research Seminar until next week because three events is enough for one blog. The three events I have focused on are: the Kent history postgraduates’ workshop, the ‘‘Sense of Place’: Imagination and the landscapes of Kent’ symposium (I missed the excursion on the following day) and the talk given by Professor Brent Nelson and his colleague from the University of Saskatchewan, who are in Canterbury with their students to look at the Bargrave collection.

As last week, I’m going to work chronologically which means the first event is the Kent history postgraduate workshop. Some of the postgraduates are not actually based in Canterbury, but of those that are the majority were gathered in the meeting last week, the discussion led by two doctoral students, Lily Hawker-Yates and Jacie Cole. Both were recipients of awards from the Ian Coulson Memorial Postgraduate Award fund last year, which has helped them to attend research skills training sessions in London, as well as travel to London archives. Hopefully, other students will also benefit from the fund this year as the Centre increases the number of postgraduates working on Kentish topics.

To return to the workshop, the idea is to work co-operatively by exploring theoretical topics and practical issues that most will be encountering in one form or another so that as a group we can draw on the expertise within the room, as well as gaining practice at giving presentations and leading discussions. This time we were examining the problems of trying to tap into the wealth of secondary literature that we know is out there but is difficult to access through some online library systems. Thus, we considered the range of materials available at the Institute of Historical Research, especially the local and regional history collections, as well as how it may be feasible to gain access to the Senate House library in the same London building. Nor were secondary sources the only materials causing issues and we also explored the range of primary sources that Lily and Jacie might be able to use, their advantages and pitfalls. The particular focus was on issues surrounding the academic use of oral history, especially how these needed to be understood and taken into consideration, but that as a research method in made perfect sense when thinking about how people in Kent managed problems surround food during the Second World War.

Having explored these issues, the last part of the session comprised a discussion about a book extract provided by Lily on the researcher’s approaches to his topic where the evidence was fragmented and relatively limited. This extract also offered an assessment of the critical literature. Although nobody in the group is looking at anything similar in terms of their research topics, this did not matter and, indeed, it was in some ways advantageous. Consequently, we were able to take a ‘step back’ from the article and consider his ideas critically. For example, these included a discussion on his apparent naïve use of the secondary literature because he seemed to display little if any appreciation of the cultural context of ‘his’ historians, either in time or space. Similarly, with regard to his primary sources, he couched his discussion in what sounded critically sophisticated, but when interrogated wasn’t. Thus, as the group concluded, by seeing what he hadn’t done they had a better idea of what was needed with respect to thinking critically about their theoretical approaches and their evidence.

Carolyn Oulton discusses Margate.

The next event I want to turn to is the ‘Sense of Place’ symposium, which organised by the Geography Research Group, in particular by Dr Peter Vujakovic, who was ably assisted by Dr Alexander Kent and Dr Julia Maxted. Initially, as Peter explained, the idea had been for this to be an internal Christ Church event, but because there was interest from outside parties, it had been opened up to bring in a number of organisations, both academic and community-based. As I said at the start, the second day comprised a field trip to the Elham Valley and Folkestone, I think, but unfortunately I had to miss that, so here is a short report of the first day. Peter chaired the first session that comprised two presentations by three people. Professor Carolyn Oulton took her audience to Victorian and early 20th-century Thanet and introduced people to the popular literature that was produced to encourage visitors to the holiday landscapes of Margate and Ramsgate, although, interestingly, there seemed to be much less on genteel Broadstairs. In addition to booklets that had cover illustrations which portrayed somewhat rakish ‘swells’ and ‘knowing’ young ladies, she provided cartoons from Punch’s rival, the satirical magazine Judy that ran from 1867 until 1907. As Carolyn demonstrated, such textual and visual representations employed the idea of ‘bad’ behaviour being linked to holiday reading of a book, for the nice young lady might appear to have her nose in a book but was in reality sizing up the young men. Nor were these young women only looking for a suitable husband, but might have more short-term priorities, even if their mothers’ priorities were somewhat different. As she also pointed out, there were important class implications within these cultural representations, which meant as well as these middle class characters there were also other cartoonists and writers who used Cockney types to highlight different cultural references. Indeed, as she concluded just how people got to Thanet, especially Margate, became a significant marker – the pier and railway station providing critical portals into this world of the Victorian and Edwardian holiday.

Lesley Hardy considers historical fiction writers.

Dr Lesley Hardy and Brian Hawkins gave the second presentation in this session. Although they covered a number of landscapes, I’m going to concentrate on Lesley’s assessment of Richborough, and ideas about ‘feeling the past’ through place. As her starting point, she looked at the comments of Hilary Mantel and Rosemary Sutcliffe, especially the former’s ideas about the links between history and creative representations of the past, and Sutcliffe’s statement that she was happiest at home in Roman Britain, ‘inhabiting’ this past, in particular, at Roman Richborough where she set several of her novels. Lesley’s research on such perceptions of the past has also involved her interrogation of the ideas of antiquarians such as William Camden, John Leland and William Stukeley, who had a particular fascination with Kent, and Richborough. For Lesley, Richborough has a particular value because it offers a time depth in terms of its Roman history – from the Claudian invasion to the last vestiges of Roman occupation and the line of Saxon Shore Forts of the 5th century. As a means of extending this time-space dimension and a sense of the past, Lesley discussed Platonic and Aristotelian concepts on space before drawing on those of Galileo. In particular, she discussed his idea of infinite space that eradicates the sense of place because it conceptually bursts the boundedness of space – interesting ideas that to a degree were taken up by speakers in the next session on literary landscapes and the imagination.

Although interesting, I pass over Dr Julia Maxted’s paper on Edward Thomas and English downland because she was talking about Wiltshire and Hampshire, and consider the next presentation on Kent landscapes. Dr Simon Wilson looked at the works of Jocelyn Brooke, whose summers spent at Bishopsbourne during his childhood and then as an adult permanently from 1938, except when he was serving in the military during WWII, greatly stimulated his imagination. The mythical world Brooke created in his mind drew on the hollow lanes, water towers and other structures in the Countryside, peopled by agricultural labourers on the surface and miners underground, that was beyond the English Eden of Bishopbourne. For him, this dark, primeval, subterranean otherness was as winter to the genteel romantic order of Bishopbourne’s high summer, with its tea on the lawn. Thus, as Simon discussed what we are seeing is the interplay between mind and landscape, as each works on the other, and just as we see this in Brooke’s east Kent, we can also see similar processes at work in Hardy’s Dorset.

Mike Bintley examines land boundaries.

Keeping with the Kent landscape, Dr Mike Bintley drew on the ideas of Lambros Malafouris and others on materialism to show his audience the poetics of Anglo-Saxon perambulations as seen in the description of land boundaries. His example concerned the bounds of eight sulungs at Godmersham found in a grant that the late Nicholas Brooks considered is rather later than the 9th century it purports to be. However, this was not Mike’s point, rather having set the bounds out in long lines as the scribe would have done to make maximum use of the vellum, he read them aloud to let his audience gain a feel for the language and the metrical structure. As he said, the bounds for practical purposes needed to use certain formulaic words and phrases, as well as the precise features taken from the landscape. Nevertheless, this would not have detracted from its poetics, and some of the landscape features would have been advantageous, as either possessive adjectival clauses or the different Old English words for hill, pond and woodland. Such examples would seem to highlight the importance of orality and the poetics of everyday language, and, even though it is not possible to recreate accurately the process whereby this communal knowledge became fixed (fossilized) in written form, it would seem to demonstrate a cultural valuing of prose-poems in late Anglo-Saxon society.

After lunch, the group explored matters of space, place and society. The first of these was my examination of civic uses of two medieval urban spaces, firstly in Canterbury and then Sandwich, which illustrated ideas about boundaries, jurisdiction (church/civic), power and control, appropriation, memory, and legacy. Just taking the Canterbury example and noting a few points, the Buttermarket (former Bullstake) was and remains a boundary, although permeable, between civic and church space, the demarcation being and represented by Christ Church gate. For this gate is still shut in the evening and overnight, just as it was in medieval times. Nonetheless, commerce pierced this barrier, there being shops on either side in the Middle Ages, as well as the great fair that was held annually within the cathedral precincts. Furthermore, the Bullstake as civic space was a place of proclamations and thus bounded through aurality as civic, albeit many of the buildings surrounding this open space off which the sound rebounded belonged to Christ Church Priory. Yet, the civic authorities jurisdiction over this area was probably only totally surrendered once, and then not to the monastery but to the king. As historically a royal city, Canterbury had received its various privileges from numerous kings but these could also be taken way. This space as representative of the balance of power between city and king was demonstrated in 1471 when Edward IV chose to have the city’s mayor executed there for treason, a stark reminder of the politics of space. And, even though there are no contemporary maps, the sense of place as a palimpsest can be seen using a civic map of c.1640 which shows Canterbury as a continuing space of contested places, albeit the protagonists on show here are the civic authorities and the archbishop.

Leonie Hicks discusses theoretical ideas on landscape.

Moving back in time, Dr Leonie Hicks discussed the construction and use of landscape in Norman chronicles. Drawing on ideas from archaeology and geography, including studies by Matthew Johnson and the late Doreen Massey, Leonie looked in particular at the works of William of Poitiers, Orderic Vitalis and Eadmer concerning the military landscape of Dover and the ecclesiastical landscape of Canterbury. Such landscapes in Anglo-Norman England are part of Leonie’s much larger project on Norman landscapes that stretches from Ireland in the west to the Holy Land in the east. Regarding William of Poitiers’ account of his master Duke William’s campaign through Kent after his success at Hastings, the chronicler drew a flattering picture of the duke by contrasting his exploits with those of Julius Caesar, including aspects of the landscape and the poor quality of the men of Kent who failed to exploit their local knowledge. Moreover, using the same idea of a palimpsest through the layering of her textual authorities who saw copying as providing authenticity and antiquity, rather than a sense of plagiarism, Leonie showed how this could also be seen to be at work in the landscape itself. She illustrated these ideas using Canterbury to demonstrate how the Normans sought to explain what had happened post 1066 by drawing on what had gone before and thus the rightfulness of their God-ordained conquest of England.

Claire Bartram demonstrates spatial links among gentry families in Kent.

Dr Claire Bartram took the audience into the 16th century to examine ‘Mapping sociability in Elizabethan Kent’. As she said, provincial book culture has only recently begun to receive much scholarly attention, but that she believes this is an immensely fruitful area, especially in the county known as the ‘Garden of England’ (sorry!). Nevertheless, keeping with this agrarian theme, the writing of books about hop-growing, market gardening and how to improve animal husbandry offer evidence of social interaction among the county’s Protestant gentry that was further reinforced through patronage, office holding, marriage, topography, and social contacts. Employing ideas from the Classics, as well as from a ‘purer’ Anglo-Saxon past, writers such as William Lambarde and Barnabe Googe deployed the language of English to highlight matters of authority and antiquity. Naming was of special importance, whether this was place names, the names of reliable informants or those who formed part of the expectant audience for the various works. Moreover, the distance between author and audience might disappear, where, for example, authors worked in collaboration to create works from plays to reproduce tried and tested animal cures. Thus oral and written culture were in frequent dialogue in Elizabethan Kent, the social mapping on the page a reflection of the social interaction that took place in the many gentry households across the county.

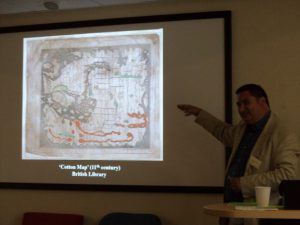

Alexander Kent discusses early map-making.

The final presentation was given by Dr Alexander Kent. He explored Canterbury’s role as a centre for map-making from perhaps the 11th century (the other potential ‘home’ of this early map is thought to be Winchester). However, as with map-making generally, it was not until the later 16th century that such work became more widespread. Alexander showed the audience a range of examples from Elizabethan Canterbury, which viewed buildings from their side elevation and were still rather schematic having circular city walls. Nor were the labels of prominent buildings always accurate, yet they did demonstrate a marked shift from their medieval forerunners. Nonetheless, it was not until the mid/late 17th century that accuracy in modern terms seems to have been viewed as the most important factor, rather than portraying an ideological viewpoint. These early modern maps were produced by various dynasties of surveyors for lay landowners who wished to demonstrate their land holding credentials. Thus, these were working documents – part of the pragmatic literacy of estate management – commissioned by rising yeoman and minor noble families who were loyal to the Commonwealth, as well as attractive marks of authority and civility. Such ideas were probably not that far from the minds of the cathedral hierarchy at Canterbury after Charles II’s restoration when they, too, apparently commissioned estate map-making. If this was the peak of such map-making, it was not the end, and, as Alexander explained, cartography remained important in Canterbury into the 18th century, albeit by the 19th century national issues such as tithe and the Ordinance Survey were coming to the fore. Moreover, the 20th century brought even greater international mapping coverage in the form of a Soviet map of Canterbury from 1981. Thus, Canterbury’s place as a centre of cartography had a remarkable time-depth, and the resultant discussion after Alexander’s talk not only considered the city’s sense of place but that of Kent across the centuries – all in all a very productive and enjoyable day.

Turning now to the talk given by Brent Nelson and Tracene Harvey at Canterbury Christ Church under the Centre to an audience drawn from the cathedral archives and the University of Kent, as well as staff members from History at CCCU and Brent’s students. Brent and Tracene are working on a large digital humanities project on collectors and collecting during the period 1580-1700 in England and Scotland, with a particular focus on the John Bargrave collection at Canterbury Cathedral Archives and Library, which is held in the original 17th century cabinets of curiosities. This state-funded project comes under the Digital Research Centre at the University of Saskatchewan, and is also an integral part of certain undergraduate modules in Classics, Medieval and Renaissance studies at the university. To offer students the chance to undertake original research, Brent and Tracene have brought students to England to work on the collections, and the group working in Canterbury this week are the third group of lucky students.

Brent Nelson explores items from the Bargrave collection.

To provide an idea of what this digital humanities project is hoping to achieve, Brent started by summarising what we know about the collectors and their collections regarding their social status, their interests and how they sought to build up their collections. These included Sir Thomas Browne (1605-82) from Norfolk whose professional interest as a doctor seems to have informed his collecting that included as ostrich. Such men, and they were almost exclusively men, first and foremost had the leisure time and the money to collect, whether this meant travelling abroad or corresponding with other collectors or middlemen to acquire particular items.

However, many of these collections no longer physically exist, except for a few such as the John Tradescants (father and son) at the Ashmolean in Oxford, and perhaps one of the most complete is John Bargrave’s collection that is still preserved in its original cabinets. Furthermore, there are still documentary records in Bargrave’s own hand, including journals covering his European travels, as well as more detailed notebooks on the coins produced by another, later cathedral canon Samuel Shuckford. Using these sources – the material culture of the items in the cabinets and the cabinets themselves, with the textual materials of labels, journals, inventories and notebooks, and concentrating on the coins, Brent described how he, Tracene and the students are producing a digital catalogue. This he describes as a ‘digital ark’ that will allow scholars the opportunity to browse and search the collections, thereby making connections and discoveries which are impossible at present because of the scattered and fragmentary nature of the sources. This is an excellent idea and has similarities to a much smaller project that Professor Catherine Richardson and the IT department at the University of Kent undertook several years ago. Indeed, the audience greatly enjoyed the presentation, as was obvious from the questions afterwards, and such international collaboration is excellent for Canterbury as it is for Saskatchewan.

Thus, the Centre has been involved in several exciting events again over the last week and in the next blog I will highlight forthcoming events, as well as reporting on two presentations by former postgraduates at Christ Church: Dr Mark Hutchinson, who is now lecturing at the University of Durham, and Charlotte Young who is currently working on her doctorate in London.

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 1070

1070