I thought this week I would first alert you to the notices about exciting upcoming events towards the end of this week’s blog, but before I get to these, I’ll be reporting on the most recent two events.

On Saturday 24 September over eighty people gathered in the Christ Church Powell lecture theatre to see nine presentations under the title ‘Resistance and Revolt in Kent from the Conquest to the Present’. To begin and to provide an idea of the project with what he thinks should be the main themes, Professor David Killingray highlighted how people in Kent had over the centuries been involved, if not instrumental in a wide range of violent protests, from the various rebellions of the Middle Ages to the miners’ strikes of the 20th century as people sought to bring their grievances to the attention of those in power. He also considered the relationship between local affrays involving a small number of people and full-scale riots, and how the crowd could become a mob, as well as what might be seen as more passive forms of protest.

David wants to explore ideas about communication, the role of rumour and written texts such as pamphlets, ballads and newspapers, and, of course, these days the internet and multi-media platforms. He is equally interested in who takes part and how we might characterise groups using, for example, gender, locality, socio-economic status and age. Moreover, he is concerned to examine those that didn’t take part and the role of intimidation, as well as the victims of such violent protest because he feels they do not receive enough attention.

With this as the conference’s backdrop, the first session comprised Dr Andrew Richardson’s assessment of the role of William of Cassingham in the First Barons’ War ie the civil war during King John’s reign that extended into that of his very young son and drew in the French in the form of Prince Louis’ forces. As Andrew said, this war demonstrates the complexity of cross-Channel politics, and for William led to his commanding a large group of archers who fought a guerrilla war in the Weald in support of John against the French. Nor was this the extent of William’s exploits on behalf of the English monarchy for following John’s death and the accession of the young Henry III, William ambushed Louis and his troops, forcing them to retire to the coast from whence they returned to France.

On their return to England to reinforce their siege camp at Dover, William led his armed band against them forcing them to sail round to Sandwich. Following the defeat of Louis and the barons at first Lincoln and Sandwich, William was rewarded by the crown and seems to have remained a leading man in the Weald for the rest of his life. However, the problem is exactly where and while he is linked to Kensham, there is the possibility that there is also some connection to the earthwork at Castle Toll in neighbouring Lossenham. As an archaeologist, Andrew is keen to explore this angle and permission has been gained to do some archaeological excavations on the site of the latter. Thus, William of Cassingham presents us with a guerrilla fighter, the victims primarily being Louis’ French forces.

In some ways keeping with the idea of victims, Dr Dean Irwin looked at the action done to and the actions taken by the Jews of Canterbury in the 13th century. Dean highlighted how the Canterbury Jews had shown considerable resilience on various occasions, not least how a few Jews from the city got caught up in the coin-clipping incident that led to the arrest, imprisonment and execution at the Tower of London of almost half the Jews held, including five Canterbury. Regarding a more local incident, but part of a much wider dispute, the Canterbury Jews are known to have aided the monks of Christ Church Priory against their archbishop in the ‘Hackington affair’ when they threw victuals over the precinct walls to the monks, as well as offering spiritual support.

Moving on about sixty odd years, Dean discussed several incidents involving the Canterbury Jews in the 1260s, especially the precarious position they found themselves when confronted by the forces of Gilbert de Clare. He also looked at a specific document from the Exchequer Rolls regarding how the Canterbury Jews were very wary about the arrival of other Jews who had returned to England following persecution. Thus, although not always victims, but at times having agency, nevertheless in David’s terms this aspect of ‘Resistance’ seems most appropriate for at least some incidents involving the Jews in England. If you would like to find out more, please see a new podcast featuring Dean: https://shows.acast.com/historyextra/episodes/what-can-one-woman-reveal-about-jewish-life-in-medieval-engl?fbclid=IwAR3qqSe_khYYFatZrRXbVBe-53KVDDaLjHqtFrZ6qSfrykd9QzRyo1QR2_U

Moving forward in time to one of the later events of the Wars of the Roses, I took the audience through the lead-up to the Fauconberg Rebellion before going through briefly what happened during the Rising, and then what happened after Edward IV came in triumph to Canterbury to quash what remained of the rebels in 1471. For as well as the execution of Canterbury’s mayor in the area of the Bulstake (today’s Buttermarket) just outside Christ Church gate, we have a good idea of the punishment metered out to about 200 of his followers from Canterbury. We can also look at what may have drawn these men to the mayor’s side, whether it was shared ties linked to family, neighbourhood and occupation, as well as how Edward seems to have adopted a pragmatic approach once he had dealt with the ringleaders, acknowledging the need to keep experienced men in civic office in the city.

Keeping with the idea of the interplay between central authority and regional grievances and responses, Dr Stuart Palmer explored Wyatt’s Rebellion against the proposed marriage between Queen Mary and Philip in 1554. Although part of a potentially more nationalised revolt, it was really only Kent which became actively involved when Wyatt called out his supporters to march on London. However, his demands lacked clarity and while he did collect some followers, primarily from mid-Kent, especially the Maidstone area and the Medway valley, what is perhaps more interesting his appeal seems to have drawn in members of the county’s old gentry families from mid and west Kent.

Yet while he and his force did march on London, aided by defectors from the very aged Duke of Norfolk’s troops sent to quash the rebellion, they were not welcomed by the Londoners as they had hoped and finding it impossible to cross London Bridge and then Kingston Bridge, they laid down their arms at Ludgate. As Stuart said, this stiff opposition by the Londoners who stayed loyal to the crown may in part be a reflection of Mary’s stirring speech at the Guildhall, a masterful piece of Tudor rhetoric. Furthermore, he thinks that in some ways this rebellion showed the futility of such actions and that the gentry even more saw the value of deploying Parliament as a means to seek redress of their grievances.

After lunch we moved on to 17th-century Kent and Dr Lorraine Flisher explained how religion in the form of non-conformity became a major force in the political situation in the early decades right up to the Civil War. As she said, there was considerable questioning of the government and king’s stance regarding the need for bishops with opposition becoming more strident. In some ways this was a product of such factors as the arrival of the ‘Stranger’ populations, growing levels of literacy, the ideas of Robert Brown, the association of like-minded believers who formed conventicles, and the influence of the ‘godly’. Moreover, as well as in the Weald where there was a long history of heterodoxy, other areas in Kent similarly became radical ‘hotspots’, such as Egerton, Ashford, Boxley and Sutton Valance.

Lorraine, also discussed the role of emigration to the Americas, including Robert Cushman and the Mayflower voyage of 1620, before examining the responses of different areas in Kent to the opportunities presented for greater religious diversity/freedom in the late 1640s and 1650s, including the Ranters in Benenden and Smarden, a Digger colony at Boxley, early Baptists at Biddenden and Congregationalists at Staplehurst. Not that these survived the return of the monarchy and the restitution of the bishops, and in the final section of her paper, Lorraine took us through the changes under the later Stuarts.

Moving on to another aspect of opposition, Professor Carl Griffin discussed how certain local protests didn’t lead to full-scale revolts and yet could have done, including David Masters’ call for a revolutionary society in 1794 at Kenardington. For if such incidents were outside the national waves of food rioting or at a time when other political issues were to the fore, they could be said to be dead ends. In contrast, even though the destruction of a threshing machine at Wigmore Court Farm in the Elham valley could, too, have been a sole incident, the fact that it was followed by several other such attacks is significant, being the start of what are now known as the Swing Riots. Probably equally important is the leniency of the punishment metered out by the court, which presumably encouraged further protests by agricultural labourers. Additionally, as Carl said, there was common ground between labourers and farmers, the latter keen to protest about tithe and rent levels, while opposition to low levels of poor relief was yet another grievance voiced by protestors from places such as the Weald and the district around Maidstone. Moreover, Carl believes those seeking to protest were aware of the extent they might be able to go without facing major repression from the authorities and that while the Tolpuddle martyrs may continue to be seen as the beginnings of Trade Unionism, what was happening in Kent deserves to be recognised for its early contribution to such forms of organised collective action.

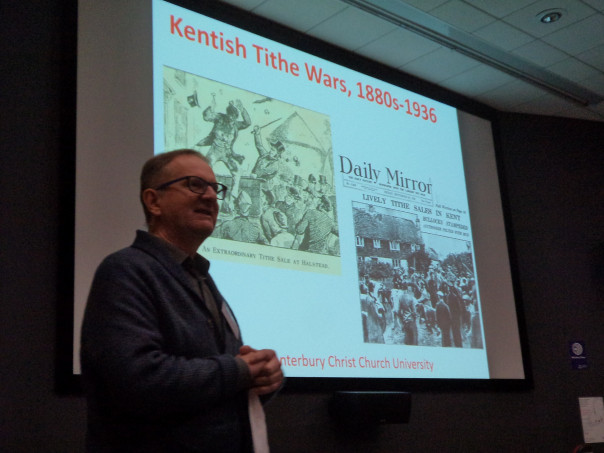

Dr John Bulaitis examined the issue of tithe, giving a brief summary of opposition in post-Reformation Kent before moving on to the early 19th century to discuss how even within the Anglican Church there was a feeling that reform was necessary. Under the 1836 Tithe Commutation Act it was transformed into a rent charge, forming part of the great Whig reform package while at the same time trying to change as little as possible. Furthermore, arable farmers paid more than those involved in livestock farming, and fruit and hop growers were especially hit, while those who did not pay found themselves the victims of distraint to cover the debt. In Kent opposition was voiced in the early 1880s when an auction was disrupted at Halstead and even though the 1891 new Tithe Act meant the tithe was to be collected from the landowner rather than the tenant, opposition blew up again in the 1930s. Owner-occupiers as farmers resisted through the disruption of distraint sales, auctioneers and dealers harassed in various ways. Additionally, farmers sought to become more organised, forming the Tithe Payers Association and one of the leading opponents of tithe, the Rev Kenward, is still commemorated, tithe only finally abolished in the 1970s.

The final paper was given by David Killingray, who considered how protest and politics have changed since the late 19th century. He looked at several periods of conflict and how coming into the 21st century the way people communicate has changed to such a degree that this may have considerable consequences for who, how and why people are prepared to challenge authority. This was a great way to pull together the various threads that had become evident throughout the day and the obvious interest of audience members was clear during the whole conference.

Turning now to the Michael Nightingale Lecture this week, I first announced that Dr Diane Heath is looking for more volunteers for her NHLF-funded ‘Medieval Animals Heritage’ project. She and some of her volunteers had a stall in the Old Sessions foyer during the wine reception prior to the lecture, and among the activities was voting to name the ‘Green Dragon’ on the Christ Church campus. This also provided an excellent photo opportunity, as you can see.

Returning to proceedings, the Lord Mayor, Cllr Anne Dekker, kindly presented certificates to the five Ian Coulson Memorial Postgraduate Award holders this year: Tracey Dessoy who is researching gentry women in east Kent during the 12th and 13th centuries; Kieron Hoyle who has just started on a doctorate on the role of the Maison Dieu in Dover under the later Tudors; Peter Joyce who is exploring poverty and the treatment of the poor in the lower Medway area; Jason Mazzocchi who is about to start on a project on the Cinque Ports in the early 17th century, and Jane Richardson who is working on three medieval religious houses in west Kent. For those interested in why the Ian Coulson Awards, please see: https://blogs.canterbury.ac.uk/kenthistory/ian-coulson-and-kent/ and there are other similarly named awards in Kent and beyond, another indicator of the regard in which he is held.

Turning to the Centre’s main partner for this Lecture Dr John Nightingale, the chairman of the trustees of the Agricultural Museum Brook introduced Dr Philippa Mesiano who has just joined the staff as part of the NHLF-funded project to engage new audiences for the Museum. Philippa then came to the front to explain her new role and how she is looking for volunteers to get involved in various projects, including a review of the Museum’s collections. She has lots of ideas about how the Museum might attract new audiences and she is also keen to hear from people about what they would like in terms of workshops and other activities. Please go to the Museum’s website and get in touch: https://www.agriculturalmuseumbrook.org.uk/

Thereafter we turned to the main event of the evening, and it gave me great pleasure to introduce Dr Graham Bradley, one of the trustees, a long-time resident of Brook and the author of Brook: A Village in Kent (2013) to speak on ‘An Agricultural History of Brook’. Graham divided his lecture into two main sections. He started by providing a history of Brook, discussing a 9th-century charter and Domesday to explore what they can tell us about the size of this manor on the fertile Gault clay strip in the shadow of the Downs, and sandwiched between the Downs and the Greensand ridge, all part of the Wealden dome. Graham then considered the likelihood that this Christ Church Priory manor’s first church pre-dated the Conquest, possibly on the same site as the present medieval church, as well as the various moated court lodges of which we know about two from documentary evidence, the third being the present Court Lodge from the late 14th century and constructed about the same date as the grange barn (now the Museum). He also explored the other buildings that made up the home farm, such as the mill and granary, and the much later oast house, and how they were in the Church’s ownership until 1862, then in lay hands before becoming part of Wye College in the mid-1950. Additionally, Graham discussed the size and form of the parish over the centuries, as well as mentioning the dens in the Weald that had been part of the medieval manor.

The second part of his talk looked at activities linked to arable farming using examples from the Museum’s collection to illustrate his points. Thus, for example, he showed us a turn-wrest plough, a fiddle drill, a reaper-binder, various threshing machines, as well as how the oast house would have been used to bring the moisture content of the hops down from 80% to 8%.

This was fascinating and the over 50-strong audience was very appreciative of Graham’s lecture, a point reiterated by John Nightingale in his vote of thanks, and after the applause had died down, several people came to ask questions and talk to Graham, including the Lord Mayor.

Now before I get to future events, I thought I would just mention that the Kent History Postgraduates group met for a catch up this week. It was great to hear how people are getting on, especially some of the discoveries they are making – more in future blogs, as well as to sympathise with those who have experienced a range of difficulties over the summer, which has hampered progress concerning their research. So thanks as always to the postgraduates who were ‘there’ and next time we will have a hybrid session for Peter Joyce’s presentation.

Now to the notices in chronological order, and there will be more detail next week. On Thursday 6 October, Dr Heidi Stoner, a lecturer in early medieval archaeology at CCCU, will be giving a talk in Old Sessions at 7pm as a joint CKHH and FCAT lecture on ‘Fallen and Broken: Remembering and Creating the past in the Late Insular Church’. All welcome and donations of £3 are sought from non-student visitors.

Then on Tuesday 11 October the Centre with St Paul’s church will be hosting at St Paul’s church at 7pm an ‘in conversation’ event where CCCU’s Dr Ralph Norman will discuss with Pamela Roberts her new book on the story of James Arthur Harley 1873-1943, a Black Edwardian intellectual who served as an Anglian priest at Deal. Again, all welcome and there will be a retiring collection for church funds.

The following Saturday 15 October, the Centre is a partner with KAS, the University of Kent and the Royal Engineers Museum in the ‘Medway History Showcase’, which stems from Professor Mark Connolly’s work last spring and is now being organised by Peter Joyce. This event at the Royal Engineers Museum in Gillingham, 10am to 4pm, will feature the activities of museums, archives universities and local and history group through exhibition stands and a series of short talks on Kent history topics. Tickets via https://tinyurl.com/mr2pjttn Or email MHS22@mail.com

Finally, as part of the Canterbury Festival, Dr Claire Bartram has organised a week of free lunchtime (starting 1pm) talks on a range of Kent history topics from Monday 17 October to Friday 21 October. Monday and Tuesday will be at St Paul’s church featuring first John Bulaitis and secondly Professor Carolyn Oulton. Wednesday sees us in Old Sessions in the old court room lecture theatre for Michelle Crowther, Thursday’s lecture given by Dr Maria Diemling will be in the university chapel, and on Friday Dr Martin Watts will be back in Old Sessions. Do come along, no booking required.

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 2269

2269