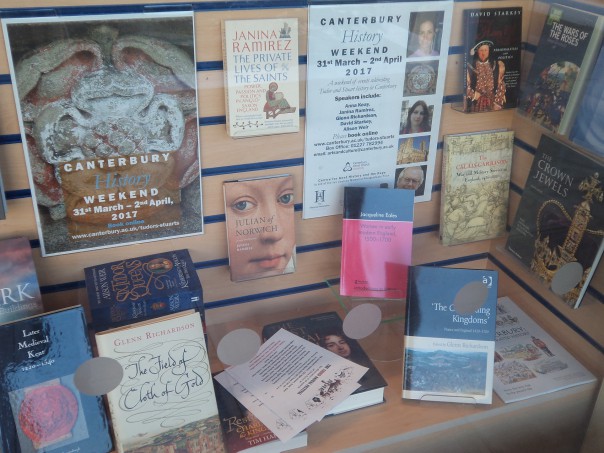

We are now just a fortnight away from the Tudors and Stuarts Weekend and excitement is growing as we look forward to welcoming speakers such as Alison Weir, David Starkey, Janina Ramirez, Glenn Richardson and Anna Keay to Canterbury Christ Church.

Similarly, it will be excellent to welcome speakers from closer to home, including Kenneth Fincham, Amy Blakeway, David Grummitt and Sara Wolfson. In addition, it will be fantastic to see Paul Bennett and Karen Brayshaw who will be leading various tours, all of which sold out some time ago. It will be great to greet old friends, including Maria Hayward, Imogen Corrigan and Jayne Wackett, and each of these speakers will offer fascinating insights into the world of objects that was so much a part of Tudor and Stuart culture. Finally, and by no means least, we will hear lectures by Jackie Eales, Matthew Reynolds and Christopher Ware – a veritable feast from Friday evening until Sunday lunch time. If you are still undecided whether this is for you, why not have a look at the website at: www.canterbury.ac.uk/tudors-stuarts where you will find details of all the events.

Another excellent news item is that the Centre’s ‘Medieval Canterbury Weekend’ was a winner in the Faculty of Arts and Humanities Knowledge Exchange Prize competition. It was judged to have led ‘to high level impact or benefit to a community, business or institution outside academia’ through its use of public engagement. This team of Jackie Eales, Diane Heath, Louise Wilkinson and I are now considering how to use the £500 prize to further the activities of the Centre. I think we will use it for a workshop to bring together experts from the university, cathedral and outside Canterbury to consider how we might undertake Diane’s brainchild – she wants to ‘colour’ the animals on the cathedral crypt capitals using light to engage with a range of audiences because animals are wonderful indicators of emotion as understood in medieval culture. Thus, this will be an educational project as well as seeking to engage those who might traditionally have little interest in art and architecture. Although this may be one stage too far, if we can find a way of making the animals ‘dance’ that will truly remarkable – so watch this space!

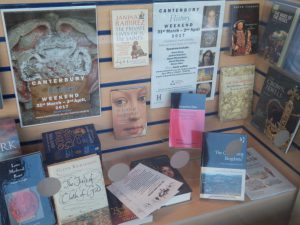

10th century censer cover, Canterbury Heritage Museum

I want to devote the rest of this blog to an excellent symposium that I attended yesterday, but before that, I want to make one point that the Dean of Canterbury Cathedral made at the lecture by Dr Christopher de Hamel, Fellow Librarian at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge. During his talk about Becket’s psalter, Christopher said that he still gets a feeling of excitement when he touches this manuscript because he sees this as comparable to shaking the archbishop’s hand – a bridge to the past that is testimony to the value of material culture. It was this point that the Dean said he would take away from the lecture, and having heard Christopher give the document a rich history, he could see how text and context are integral to understanding the importance of this precious manuscript. Without labouring the point, this is why museums, as well as libraries, are crucial and why it is vital that such institutions are treasured and cared for, not neglected and ignored.

To return to the symposium, this was organised jointly by the Centre and the Friends of Canterbury Archaeological Trust [FCAT] and was entitled ‘Normans in the Landscape’. It featured three speakers of whom two are History lecturers at Canterbury Christ Church, while Richard Eales is a retired lecturer from the University of Kent. About fifty people sat expectantly in the Old Court Hall lecture theatre, and Dr Leonie Hicks, the first speaker, outlined how the early Norman dukes used the two most important towns under their control to enhance their authority in the region. Her analysis of ducal power as articulated through command of the cityscape and the city’s hinterland at Rouen and Caen was fascinating, especially her consideration of sightlines. Among the elements which Rollo and his successors employed were the siting and building of defences, including castles; the foundation of monastic houses; the redeployment of Roman and Carolingian features; and the provision of harbours, mercantile quarters and industrial areas. Similarly ideas about wealth, good order, and strong lordship were articulated beyond the city walls through the setting aside of land for hunting by the nobility. Leonie drew on a range of evidence, including city maps and charters, but equally interesting was her use of chronicles and literary texts. I was particularly struck by the use of poetry by these early writers, especially the way writers about Caen echoed ideas previously employed to praise Rouen, on the face of it a very different city in terms of its earlier history and more recent development.

Dr Paul Dalton and his expectant audience

Many of the ideas raised by Leonie resurfaced in her colleagues’ talks. Dr Paul Dalton then took his audience to England in the aftermath of Duke William’s success at the battle of Hastings. He demonstrated how earlier historians had almost universally ignored the landscape in their assessments of what Duke William did next with regard to his march on London. For, as Paul stated, time was pressing and even though William needed to take London there were distinct disadvantages in trying to head north directly. First marching through the Weald in autumn would be foolhardy, the terrain would have been difficult, William would not have access to Roman roads, present in other parts of the county, and he would be a long way from his fleet, and safety if he needed to depart quickly. Equally, he needed to secure Kent, which meant its main coastal towns (pre-Conquest Cinque Ports?) and the ecclesiastical and earlier royal settlements of Canterbury and to a lesser extent Rochester. I do not have space here to go into his argument in detail, and it will be published in Viator in the summer, but there are a couple of points that seem especially important. Firstly, as Paul discussed, William followed accepted military practice of keeping in contact with his fleet as his main army marched eastwards and then northwards around the coast using where possible Roman roads and the coastal towns that still had the remnants of their Roman defensive works. This means he thinks William’s march to Canterbury from Dover was via Richborough – the Broken Tower of chronicle fame.

However, I’ll now leave what else William did in east Kent and turn to his march through north west Kent. If Paul is right and from Canterbury he made use of the old Roman road towards London he would have passed through Rochester, which again provided him with a sheltered anchorage for his fleet. Nevertheless, as he moved west he would have found himself much further from his fleet than at any time thus far, and it is during this section of the Norman march on London that he would have been more vulnerable. As Paul said, he is speculating here and the chronicle sources are much later, albeit local, and are riddled with errors. Yet the landscape would seem to point to the feasibility of the Swanscombe Agreement actually having more than a glimmer of truth in it, because if the Anglo-Saxons of Kent had attempted to ambush William’s army that where they ‘should’ have done so.

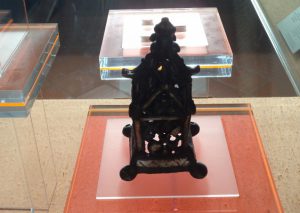

Portable sundial, c.950, Canterbury Heritage Museum

Richard Eales took up the baton and provided his audience with a summary of why castles were constructed and by whom in the post Conquest period up to c.1200. He explained how they were deployed to consolidate royal power indirectly through aristocratic rather royal building campaigns, apart from a few strategically important sites. As Richard demonstrated, castles frequently had a military function but that was far from being their sole use. Rather he highlighted how castles should be seen as multifunctional, including their ceremonial role, and that the best way to understand castle building was to draw on all available evidence for use and to assess each castle individually.

Richard demonstrated how this could be done through his analysis of Peveril Castle in Derbyshire. As he said, he had in the past viewed it as located in an isolated setting, but while he still believes the way it is sited high up in the gorge means that it was built for defence through its command of the ground on several sides, this is only part of the story. Among the other factors that he now sees as important are its position relative to the early town or proto-town of Castleton, an urban settlement that the lordly Peveril family patronised as they sought to enhance its industrial and mercantile activities. The castle is not far from the old Roman road to Chester, it is at the centre of an important royal forest – grants of venison being numerous and exceedingly significant, and there is, of course, lead mining. I’ll leave the relationship between the castle and ‘The Devil’s Arse’ to you to find out, but just to say like the other two papers, this was fascinating.

Nor was I alone in this assessment of the evening because there were a number of questions for all three speakers. The evening concluded with Dr Anthony Ward’s vote of thanks to the speakers and to the Centre for hosting such an informative and thought-provoking event. Moreover, even after that some audience members came up to ask further questions – a mark of a successful occasion.

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 692

692