Dr Richard McManus explains the real impact behind this week’s rise in national insurance contributions.

Much attention has been given to the rise in national insurance contributions that occurred this week, raising the rates that employees earn on their income by 1.25%. As a result of the combination of this rise and an increase in the band at employees start to pay this, those on average earnings will pay approximately £200 more in taxes out of their paycheck each year.

This tax rise is seen as broadly progressive, meaning that the more one earns, the bigger the increase in their rate of tax. For example, those earning £50k will pay an extra £464, and those on £100k an extra £1,089.

Importantly, this is only half of the tax rise; employers also pay national insurance and their rate is set to also rise by 1.25%. Indeed, 58% of national insurance paid comes from employers’ contributions, given both higher overall rates for businesses, and that their contributions do not decrease at higher earnings (unlike employees who rate of national insurance tax falls above incomes of £50,270). Although it is intuitive that these contributions are paid for by businesses and thus reduce profitability and dividends to shareholders, there effects are likely to be more dispersed.

Broadly speaking, there are three potential candidates for who might share the additional taxes of businesses. First, as discussed above, the businesses themselves who very literally pay the remittances to the HMRC. Second, the employees, who receive lower wages as a result of the increase in the cost of paying them to the businesses. The idea here is that businesses factor in the total cost of employment (wages, taxes and other non-pay costs) and if one of these (taxes) goes up, then another (wages) may fall. Moreover, the impact on employees is likely to be regressive; that is, those on lower incomes in a businesses will be impacted disproportionality more. Whereas those on high incomes have more bargaining power, those on lower incomes have lower power and are more replaceable. As such, any cuts in wages is likely to be distributed more to those on lower incomes in a businesses.

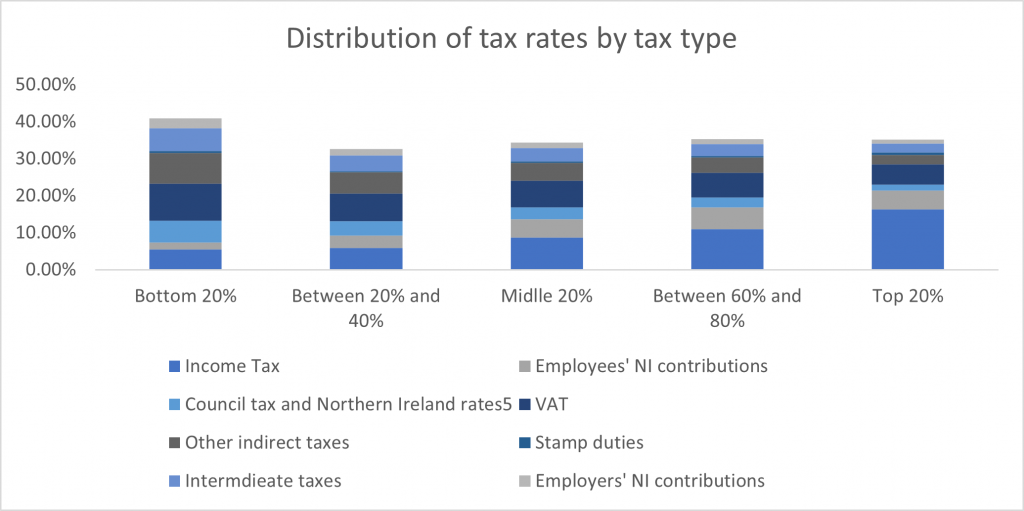

The third candidate to pay for additional tax rises on businesses is the consumer, who may contribute through high prices. Indeed, in analysis conducted by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) on the allocation of taxes across the income distribution, they assume that it is consumers who for employers’ national insurance contributions. This is in addition to VAT and other customs and duties, all taxes paid for by businesses, but assumed to be passed down to the consumer. Significantly, as poorer households consume more of their income (as they have less from which to consume, they spend proportionately more), the impact on these households of such taxes are that much greater. That is, these taxes are regressive in that households with lower incomes pay more relative to their income.

Using the ONS’s most recent data on ‘Effects of taxes and benefits on household income’ from 2017/18, identifies that those in the bottom 10% of households pay 35.1% of their income (including earned income and cash benefits) in these indirect taxes (VAT, customs and duties and employers’ national insurance contributions), whereas those in the top 10% of income pay 10.7% of their income. Focusing only on national insurance, these numbers are 3.3% and 0.9% respectively. That is, taxes that get passed down to the consumer are very regressive.

When looking at all taxes paid by households, the rate paid relative to income is broadly flat across the income distribution. That is, richer households pay higher rates of direct taxation such as income taxes and national insurance, whereas poorer households pay more through these indirect taxes on their consumption, because they consume more of their income; when taken together, tax rates are consistent across the income distribution. Although the tax rise on businesses may be less controversial and less discussed, it is likely to have bigger impacts on the economy and these impacts will be regressive, disproportionally affecting poorer households more.

Dr Richard McManus is Director of Research Development for Christ Church Business School.

Expert comment

Expert comment Jeanette Earl

Jeanette Earl 2240

2240