Richard Turney, Lecturer in the School of Humanities, looks at the legacy of Booker Prize winner John Berger.

Last week John Berger died, at the age of ninety. He was a Booker Prize-winning novelist, wrote extensively about art and photography, was a poet, a theatre-maker, an essayist, and much else besides.

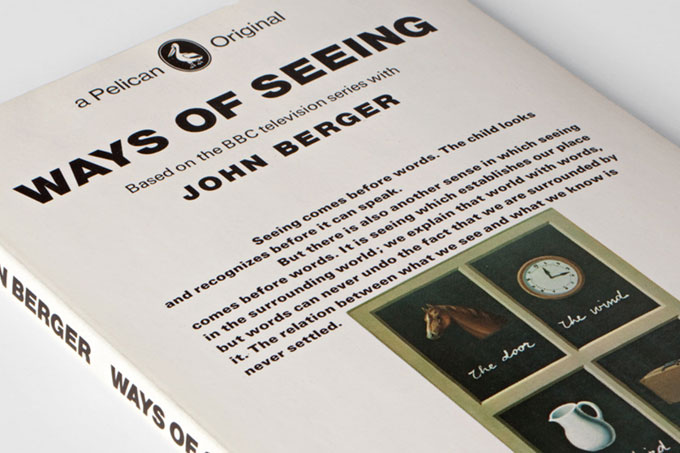

As soon as any public figure dies, we begin the process of remembering them. Berger’s passing generated some rather equivocal obituaries and mostly one-dimensional comment pieces. This is perhaps a testament to a life lived without compromise, and of the enduringly uneasy relationship Berger had with British institutions, and even with the country itself, which he left in the 1960s for France, for good. It also undoubtedly speaks of the dominance of the main source of Berger’s fame, the 1972 television programme, Ways of Seeing, and the continuing popularity of the subsequent book. It is a shame to see that so little of what has been written this week has gone much past this text and its influence, and thus much beyond an idea of Berger as a radical art critic in a flowery shirt. Welcome but fleeting exceptions, such as Tom Overton’s obituary in The Daily Telegraph, and the personal reminiscences of writers Geoff Dyer, Olivia Laing, and Ali Smith, and theatre-maker Simon McBurney, in ‘John Berger Remembered’ in The Guardian, serve to highlight the narrowness of the imprint left by the rest.

This narrowness matters, for one thing, because over the course of a sixty-year working life Berger produced some of the most extraordinary narrative prose by a British post-war writer, of astonishing diversity of form and subject-matter. Berger is a glorious writer. Full of risk and surprise, his work is underpinned by the intellectual curiosity and precise clarity of a singular gaze on the physical world, rich figurative webs, and memorably vivid characters (none more so than his representations of himself). He was an heir to Daniel Defoe, James Joyce, BS Johnson, George Orwell, and WG Sebald, among others. The result is an extremely wide and heterogeneous body of work that leads us into Parisian strip-lit launderettes, high up to the French alpage above peasant villages (where flying birds stitch and unstitch the sky) to fin-de-siècle Trieste, deep into the Chauvet caves, to the sharing of soup with a dead friend in Kraków, to 1960’s NHS hospital wards, and on and on through a tapestry of worlds, moods, and themes that is all, due to the exploratory feel, intensity, and commitment to the subject, recognizably Berger. It promises hundreds of hours of stimulation and pleasure for anyone who reads him.

That is already enough, but there is more: the tenderness and generosity with which Berger wrote makes his work pressingly important at this precise historical moment. For Berger, the narratives of those in power worked to conceal the reality of life, and he was repeatedly drawn to the powerless, the dispossessed, to the weaker side of any given struggle. He wrote about economic migrants, refugees, the inarticulate, and the homeless – wrote about their bodies, their dreams, their hands, imagined them as children. As Ali Smith quotes in her piece remembering Berger, he wrote in The Seventh Man, “To try to understand the experience of another it is necessary to dismantle the world as seen from one’s own place within it and to reassemble it as seen from his.”

Right now, to read Berger is to better connect with the tens of millions of forcibly displaced people struggling across the face of our planet, and to recognise hospitality as our best response to their experiences. This is because Berger’s prose is not just well intentioned, it is brilliant, evocative, potent, and powerful. It doesn’t describe or advocate for hospitality and empathy, it both performs and produces them. It reminds us that the message of tolerance needs art and needs talent. He leaves us with a body of work for our times.

Expert comment

Expert comment Jeanette Earl

Jeanette Earl 1861

1861