Dr Alan Bainbridge argues that a dependence in education of metrics to understand performance is eroding a student’s individuality.

“Attempts to employ neo-liberal technologies to manage and control education are the actions of the person who digs their own grave, only serving to destroy the very thing it claims to support. … This is where Jill no longer exists but for a test score”. (*Bainbridge, in press)

I wrote these words in the final paragraph for a chapter in a book that sought to reveal how the neoliberal discourse is experienced in the everyday lives of educators and students. Some may feel that my analysis is little more than a provocation designed to garner attention, where in the world of competitive academia I could achieve more ‘hits’ and ‘tweets’ as evidence of my impact. Yet, recent events make the disappearance of Jill and millions of students like her, more fact than fantasy.

Like so many colleagues working in education I have watched on in astonishment as government ministers struggle, not only to understand the system of state education they proport to govern, but in the absence of examinations, to find ways to measure and report student learning.

Experts are not needed to recognise that education is complex; a bewildering array of social, cultural, psychological and economic factors need to be considered about what, how and to whom, something should be taught. To add to the complexity, at various stages attempts are made to measure individual learning and report the outcome in relation to an entire national cohort. This has never, and will never be straightforward. To the detriment of individual ‘Jills’, recent years have seen the application of neoliberal principles of marketisation and accountancy attempt to side-step this complexity. Offering instead a simplistic and entirely unrealistic ‘cause and effect’ world of standardisation, management, inspection, accountability and ‘excellence’. The grave of what it might mean for Jill to learn while being taught by a particular teacher, in a particular school at a particular time has been dug very deep.

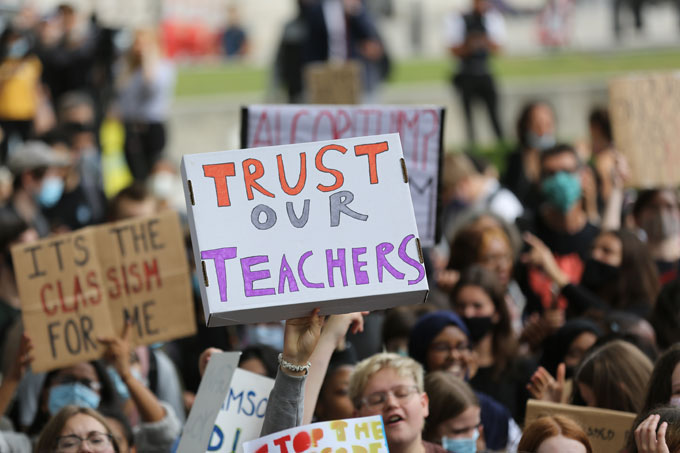

This is not the place to discuss the fine details of how well an algorithm may or may not work, or indeed the role of examinations. Rather, I shall focus on why the A Level controversy highlights, that, despite the efforts of educators, formal education, at least for our elected members, is no longer interested in individuals and why ‘Jill no longer exists but for a test score’.

In England, at least, metrics dominate formal education, from ‘baseline’ assessments of four to five year-old children in Reception classes, continuing into higher education where the ‘destination of leavers’ metric is used to report on ‘teaching quality’ measured by employment type and salary.

When such metrics are used, Jill’s ‘Jill-ness’ is hidden and can only be construed as (say) a 17 year-old female with an average IQ, from a single parent working class background, who has been predicted average A Level grades from a secondary modern school that has had very few past A Level students. The difficult and highly skilled job of those who educate Jill, will be to help Jill to come to an understanding of what her challenges are and what desires she has beyond simply a series of levels, certificates, grades and the dominant discourse that exam success leads to professional success and a lifetime of wealth and personal fulfillment.

Instead, recent events have shown that Jill has been lost to an algorithm, casting aside all that makes Jill, Jill. The skill and care of the educators in Jill’s life have been ignored and replaced with a subject type, group size and the achievements of previous students from her school.

Despite protestations of how education can transform lives, there can be no more visceral and violent example of how neoliberal technologies focus not on an individual but on institutions, on systems and not people, all the time limiting opportunity while maintaining the status quo. The horror of the A level debacle is how the design of the metric focused on those from less well off backgrounds; refusing to accept that certain members of our society were not capable of the achievements those who knew them best had judged them to be capable of.

The decisions made behind the design and use of a distant algorithm to manage and control this year’s A Level results exposes that those in positions of power, like Nelson, deliberately view education through eyes that do not want to see. These eyes do not want to see Jill, perhaps to see Jill will expose some uncomfortable truths; that education is messy and complex and difficult to fit into a world of accountability, and that, despite the purge for excellence, it is difficult to accept that a particular Jill, who wasn’t expected to be excellent, is just that.

The time has come for education to rise-up from a grave dug deep by the incursions of neoliberal thinking and to focus again on the skillful educators working thoughtfully and carefully with particular ‘Jills’, of all ages, and not the metrics that compare institutions refusing to acknowledge individual success.

Dr Alan Bainbridge is a Senior Lecturer in Education.

*Bainbridge, A. (In press). Deceptively Difficult Education: A Case for a Lifetime of Impact. In: Howard, P., Saevi, T., Foran, A. and G. Biesta, ed. Phenomenology and Educational Theory in Conversation: Back to Education Itself. Routledge: Oxon.

Expert comment

Expert comment Jeanette Earl

Jeanette Earl 1622

1622