Dr Harshad Keval asks if the temporary nature of Black History Month can support the call for a radical change in societal racial justice.

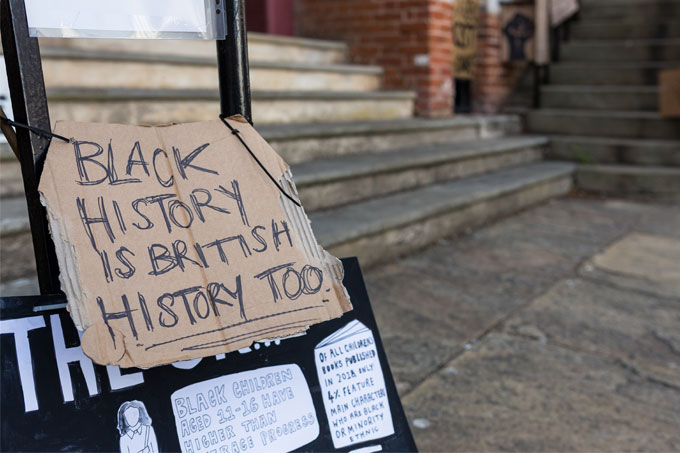

October this year will once again see the annual event now known around the UK as ‘Black History Month’ (BHM). In this brief comment, I would like to draw attention to several issues: some important misconceptualisations that can emerge from the ‘temporality’ of these events; the urgent need for what I term ‘connected race-critical analytics; and what ‘Decolonising’ must come to mean and be understood as, in this moment.

The events that generally lead up to and characterise BHM across multiple arenas of work, education and civic UK life are diverse and multileveled in their depth, scope and substance. Many events pay tributes to otherwise silenced and invisible lives, while other events and places spend more time and effort in acknowledging the powerful, integral role of black people and communities of resistance and liberation in this country’s history. The urgent need to resist against the constant negative attention on black populations is often a feature, but the attention placed on celebrating black lives, histories, families, cultures and successes is also a mark of BHM events.

As we draw closer, I have questions about the temporality of this process, and what BHM signifies when taken in the context of enduring racial inequalities. For this year, many more people have become aware, if not fully conscious, of deeply ingrained and systemic racism at many levels in society. The momentum behind this particular surge has been of course driven by the George Floyd murder, and the ensuing world-wide protests connected to Black Lives Matter. As we draw nearer to BHM, my question is what happens after this month? What happens when the social media tags #Racism and #BlackLivesMatter stop trending and become side-lines at the margin?

There is a darker truth to what these questions point to, and that is that for many people who are not subject to damaging, powerful and systemic forces of racism and racial trauma, the momentum will slow, and the societal urgency will reduce. For those who, as A. Sivanandan warned, wear their passports on their faces – an analogy one could extend to any group who suffers racialisation, it is not so simple.

The temporal nature of BHM is fundamentally linked to the highly problematic mis/understanding of what ‘race’ and ‘racism’ are, what they do, and how structures are maintained through systems of white privilege. Unless there is a deeper, transparent, and connected analysis, that emerges from the experiences, skills and insights of communities and individuals who live through and beyond racism, then BHM will, unfortunately continue, in many instances, to re-enact the tokenistic, time-limited gestures we have seen all too often.

Lastly, for Black History – whether for a month, a year, or a moment, to live up to the urgent needs of a universal social justice agenda, a connected, race-critical analytic that informs and shapes what ‘decolonising’ must come to mean, is necessary. And for this step to occur, I would like to emphasise one crucial point, and invoke the words of Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang: ‘Decolonisation is NOT a metaphor’. This means that the now bustling and so-easily commodified market place of liberal educational reform, ‘diversity’ agendas, and ‘decolonising the curriculum’ movements, can often be occupied by an ignorance of the very heart of 400 years of decoloniality and decolonial thinking itself. Everyone working with this notion would do well to use these criteria to ask, ‘What, if anything, actually is being decolonised here?’ and ‘what is simply tinkering with the comfortable periphery of change?’

Some institutional, organisational questions I think we need to bear in mind as BHM approaches are: How can a collective, reconcile the competing pressures in this difficult, COVID crisis moment, to do ‘race-equality work’ without connected race-critical thinking, with the urgent need for radical, institutional and societal racial justice that cuts across gender and class divisions? Equally important, can this depth of thinking, mobilising and change occur, without partnerships with black and minority scholars in this field? BHM necessarily requires these directions and forces in order to take on permanent meaning for all of us.

The stakes for groups and communities who so often only become visible through ‘racial’ or ‘cultural’ snapshots are as high now as they ever have been, for many the stakes are life and death.

The ultimate goal for Black History moments of course is to move beyond the temporary and be embedded in a national consciousness of belonging, without being racialised and oppressed, marginalised or silenced, or rendered as a problem to be ‘solved’. Decolonial connected, race-critical thinking is scholarship and activism that demands more than a cursory glance at narrow notions of ‘diversity’, and looks to this moment with a call for radical change.

Dr Harshad Keval is Senior Lecturer in Sociology, with specialist interests in race-critical, decolonial Sociology.

Expert comment

Expert comment Jeanette Earl

Jeanette Earl 2998

2998