Exciting news this week, we passed the thousand-ticket mark for the Medieval Canterbury Weekend 2018. There are still tickets for all the talks but some of the guided tours have now sold out. So if you haven’t already done so, why not check out the website at: www.canterbury.ac.uk/medieval-canterbury for exciting talks on wonderful medieval manuscripts (Professors Michelle Brown and Richard Gameson), fantastic stained glass windows or medieval beasts (Leonie Seliger and Dr Diane Heath).

In addition, this week I want to report on a collaboration between historians and archaeologists where the Centre will be running two workshops on understanding skeletons for Young Archaeologists Clubs in Kent. Dr Ellie Williams is an expert on osteoarchaeology and having run such workshops while she was lecturing at the University of Southampton, she is keen to undertake similar events in Canterbury. Running this under the banner of the Centre, these workshops will take place on Saturday 14 April and among her helpers will be Diane Heath and me. When we went to her office this week to plan the event, we were greeted by this skeleton and Ellie also has boxes and boxes of animal and human bones from Canterbury Archaeological Trust’s collection from their various excavations in and around Canterbury. This means the young archaeologists will see and get to handle bones from the Anglo-Saxon period, and will be able to explore what these can tell us about the people and their activities more than a thousand years ago – all very exciting!

Dr Ellie Williams’ office at Canterbury Christ Church.

Keeping with the subject of skeletons, I’ll offer a short report on Ross Lane’s lecture to members of the Centre and the Friends of Canterbury Archaeological Trust that took place on Thursday evening. Unfortunately, this clashed with Dr David Hitchcock’s (CCCU) Canterbury Historical Association lecture at Canterbury Cathedral Archives and Library where he was speaking on homeless women in early modern England. As it happened I did see him on his way over to the Cathedral Archives and I’m sure his talk was a great success.

But to return to Ross Lane and the excavation he is leading on the Trust’s behalf at St Alban’s Cathedral. As Dr John Williams, the Chairman of FCAT and an associate at the Centre, said in his introduction, this excavation began last August with the expectation that all would be finished by late autumn, however the archaeologists are still there, and it is now a race against time to finish the work in the next three weeks when the dig will end. This means as well as the archaeologists working there during the week, Paul Bennett, Director of the Trust and Visiting Professor at the Centre, is driving over and working with a group of volunteers at St Alban’s every Saturday.

Ross Lane talks to Dr John Williams

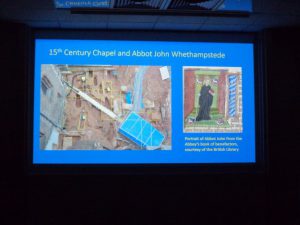

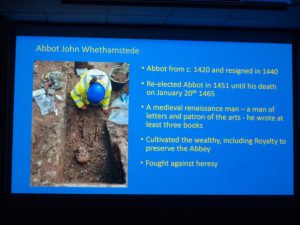

Ross began his talk by taking the audience on a whistle-stop tour around the interior of the cathedral in order to show the relationship between the present building and the site his team is excavating in the corner made by the presbytery and the south transept. As he discussed, St Alban’s is unusual in England because it was constructed, first by the Anglo-Saxons and then the Normans, of Roman brick and tile, with intact columns, too, taken from Roman Verulamium nearby. In the Middle Ages, St Alban’s Abbey was one of the wealthiest and ancient Benedictine houses, albeit its very early martyred saint was eclipsed by St Thomas of Canterbury after the archbishop’s murder in 1170. The interior of St Alban’s Cathedral (previously the abbey church) can be said to have been over restored by Edmund Beckett, 1st Baron Grimthorpe in the late 19th century, who had very definite ideas about what he thought Gothic architecture looked like and built accordingly. Nonetheless, not everything received this treatment, and, as Ross showed, there remains an ornate series of upper columns linked to Abbot John Whethamstede in bay 4 and some Norman plasterwork in bay 2. Rupert Austin, also of the Trust had previously undertaken a detailed architectural survey of the standing building, and it was his work that Ross drew on for this section of the lecture.

Ross then turned to the excavation itself, the Trust having been specifically requested by Martin Biddle, an internationally known expert and authority on St Alban’s Abbey. Initially the archaeologists were confronted by a parish graveyard that was open between 1750 and 1850, and this has produced well over a hundred burials, sometimes multiple graves and family tombs. These burials are in a very good condition with considerable amounts of coffin furniture such as studs, nails and handles, the Victorians having had a very elaborate funeral culture. As you might expect, the individuals cover a wide age range from babies to the elderly, albeit because of the location of the cemetery these were probably among the more prosperous from the local town, but child mortality in Victorian times was no respecter of wealth and social status. For Ross and his team, the sheer volume of bodies in a tightly packed site posed considerable challenges, but for social historians of pre-industrial England the results from post-excavation specialists will be extremely valuable.

Looking at the excavation and Abbot Whetehamstede’s chapel site.

However as a medievalist, I want to turn to that aspect of the excavation that involved finding the chapel, and more importantly the grave of Abbot Whethamstede. This involved some detective work because in a burial below the parish cemetery the team found three objects laid on the chest of the deceased. On investigation these were found to be copies of three papal bulls. Now it is known that John Whethamstede had obtained three edicts from Pope Martin V in 1423 and he was apparently so proud/pleased with his achievement that he had copies made of them which he kept with him at all times – even into his grave.

As some of you may know, Whetehamstede was an active senior churchman during the early decades of the 15th century on the national stage, and, even though this was not that unusual, he does stand out in some ways. Nonetheless, the papal edicts primarily cover matters relating to his monastery because they included a dispensation for the monks to be able to eat meat on certain days when this was prohibited under the Benedictine Rule; the use of a portable altar at the abbey’s London hostel, and the renewal of Pope Boniface VIII’s grant whereby the abbey could farm the income of its properties without recourse to papal, episcopal or other licences.

Abbot Whetehamstede – an amazing discovery!

This discovery of the skeleton of a known person in what is essentially an unmarked grave is extremely unusual, and, even though Abbot Whethamstede is not in the same league as Richard III, this is still very exciting. Indeed, Professor James Clark (University of Exeter), an expert on the late medieval Church, has been in contact with Ross and is now investigating the documentary records for the abbot, his chapel and monastery in the 15th century.

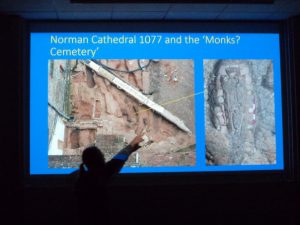

Nor is this the end of the exciting archaeological discoveries at St Alban’s because the team has found further burials associated with the Norman cathedral (built from c.1077 by Archbishop Lanfranc’s nephew). These seem to have been part of a lay cemetery from the 11th and 12th centuries and include the burial of a child, as well as women. Carbon 14 dating will be carried out in the post-excavation phase to seek to ascertain the phasing of this cemetery. Below that again the archaeologists are making further discoveries, the latest work being on an Anglo-Saxon ditch, which may relate to either a field boundary or the earlier church, a burial, and, so far, a small amount of pottery. Thus, as I said at the beginning and Ross reiterated, this is a race against time because the site needs to be cleared for building work to begin the new visitors’ centre at the cathedral, as at Canterbury part of a Heritage Lottery funded grant.

Ross points out the grave cuts.

Finally, I thought I would mention that we are very sorry that the Becket Lecture had to be cancelled last Tuesday, Professor Louise Wilkinson will be looking into the possibility of rescheduling it later this term; and last night I was delighted to partake in the Eastbridge Hospital annual dinner held in the late 12th century undercroft. Consequently, I found myself sitting between the former Lord Mayor of Canterbury Cllr George Metcalfe and Seb, who is one of the undergraduate scholars at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, aided by the Matthew Parker scholarship which Parker established in the late 16th century when he refounded Eastbridge Hospital. In addition to the excellent food and brilliant atmosphere, I had several very interesting conversations including the relationship between the London livery company of cutlers and swordsmiths and the Elephant and Castle, Huguenot apothecaries in Deal, and undergraduate dining arrangements at Cambridge. As a result of this occasion, hopefully I will soon be able to report on progress regarding the Centre’s input concerning Eastbridge Hospital’s exhibition of its history through the ages that is due to go on display there from April to the general public.

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 1276

1276