Now that we are well into January it is time to move on to the next part of the preparations for the Medieval Canterbury Weekend 2018 on 6–8 April. Speakers have been invited to send details of the books they would like Craig at the Canterbury Christ Church University bookshop to have at the book stall, and several people including Dr Janina Ramirez and Dr Helen Castor have responded already. If you have not heard about the Weekend, please check it out at www.canterbury.ac.uk/medieval-canterbury

As I reported earlier, we are aiming to attract youngsters on Friday 6 April to a storytelling session at the garden behind The Canterbury Tales visitor attraction in St Margaret’s Street near the middle of Canterbury. Dr Diane Heath of the Centre has now compiled a booklet setting out a range of storylines that The Canterbury Tales staff will develop to produce some exciting medieval tales with a Canterbury twist, including stories about the adventures of sightseeing pilgrims and the arrival of an African elephant to the city in the 13th century. As soon as more details are available I’ll pass them on, including details of where tickets can be purchased.

Professor Robert Mills (UCL) speaking on the famous elephant (at the London Medieval Society).

On the subject of news, I’m hoping to be able to report further developments on the Centre’s involvement in the planned exhibition at Eastbridge Hospital on the hospital’s history through the ages very shortly because the Eastbridge Trustees met this week. Similarly, several of the counsellors at Faversham had a meeting and we are hoping to hear from them soon regarding their responses to our proposals for a medieval Faversham exhibition. These are very exciting opportunities for the Centre, as is the ‘Maritime Kent through the Ages’ conference which, too, will include a small exhibition in the foyer of Old Sessions House on Saturday 23 June. This will be compiled by an undergraduate as part of his/her employability module, convened by Dr Sara Wolfson, because it will provide experience of working to deadlines, visiting archives or museums to research relevant topics and making that material into an interesting and informative display – valuable transferrable skills.

All of these projects are crucial to the Centre’s development, as are its encouragement of postgraduate students who are studying Kent history at CCCU and its engagement with outside groups in the promotion of the study of history using Kentish primary sources. Both activities took place this week and it is these that I will focus on here. I shall keep to the order in which they happened and therefore start with the visit of 13 ‘A’ level History students from King’s, who are in the upper sixth and thus preparing for crucial exams this summer. They were accompanied by their teacher Claire Anderson and I met them in Canterbury Cathedral Archives late Tuesday morning. Among the books we looked at were the Geneva Bible and in this workshop setting we discussed why the biblical text is often heavily annotated. In fact, for large sections of books such as Genesis the margins are completely covered in printed notes, and then someone, perhaps in the 17th century, has even added further notations in ink. We discussed why this might be and the feasibility that this Calvinist version is seeking to ensure particular readings of what were seen as key (or troublesome) passages of scripture by its intended readership, for once the Bible in English was available to all the genie wasn’t going back into the bottle!

Archbishop Bourchier’s tomb, Canterbury Cathedral

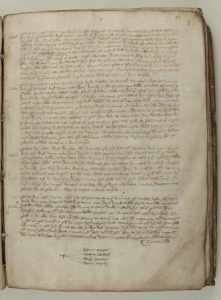

However, I want to focus on the two wills that the students also studied because they reveal ideas about religious belief, attitudes towards the poor, relationships between husbands and wives, and what constituted movable goods. The first was made by Thomas Arden of Canterbury in 1567 and has an especially long opening where he outlines his evangelical Protestant beliefs in justification by faith, his understanding of Christ’s Second Coming and the centrality of baptism. He is equally forthright about what he does not believe, and he totally rejects the value Catholics placed on ‘mediators’ on earth and in heaven because, as he says, there is ‘one mediator between god & man, which is Jhesus Chryste’. Similarly, he casts scorn on Catholic good works as a means of achieving salvation, instead seeing such giving of his temporal goods ‘as the frutes of faythe’ for they reveal Christ’s merits, not Thomas’. A proposition he reiterates in ‘a good worke makethe not a good man, but a good man makethe a good worke, for faythe makethe a man bothe good & righteous, for a righteous man lyvethe by faythe’. Thus, I feel, Thomas was just the sort of man who, if he had lived long enough (not printed in England until 1576), would have owned a copy of the Geneva Bible.

Interestingly, there is little in his will about his charitable giving, and for that I’ll turn to Richard Furner. He made his will almost a decade later and though apparently a convinced Protestant he does not go beyond the conventions of the times. Where his will is fascinating is his employment of the wards of Canterbury rather than the parishes as his units of distribution – for example allocating £3 in alms to Worthgate Ward. He also seeks to aid various disadvantaged groups in Canterbury such as poor artisans and orphans, and he actually names some of the aged poor, destitute widows and poor maidens who should be among the beneficiaries. Such categorising suggests a knowledge of people’s needs, the value placed on local knowledge and residence, and the importance of the civic governors as mediators in this process of public alms giving. Consequently, it is perhaps not surprising that among his bequests is one of £3 to be used to give a dinner for the mayor, aldermen and common counsellors at some inn or tavern in Canterbury.

14th-century wills proved in the Burgmote Court of Canterbury.

Keeping with Richard’s will, there is an interesting reference to his wife’s jointure that had been set previously in a deed which was apparently in the safe-keeping of Henry Courte’s widow. Under its conditions Joan, Richard’s wife, was to have one of his tenements in St Margaret’s parish for her life, which was currently rented to a James Bennett. She was also to receive £50 and a gold ring from Richard’s goods. However, Richard seems to have had misgivings about his wife’s regard for the provisions of her jointure because he stipulated that if she tried to enforce what she saw as her rights to any other part of his property, his executors were to withhold any of the bequests he had given to her.

Turning to the question of what constituted Richard’s movable goods, such items as the great cauldron, its trivet, two long spits and the great racks which were to go to Thomas Maye suggest these constitute much of Richard’s kitchen furnishings. His parlour may have been similarly denuded of furniture because John Maye was to receive a close cupboard, a joined chair, and a frame table with a form. Yet it is the wainscot and glass windows that seemingly show just how valuable and movable such items could be because Richard’s executors were to sell these as separate items for the best possible price.

I hope these few examples give you an idea of the richness of these documents for investigating Elizabethan society, and from the amount of discussion on Tuesday this was not lost on the students either who enjoyed their archives visit. Next month it is the turn of the Classics students and then in March the lower sixth History students will be exploring early Tudor society through documentary sources, and Claire, their teacher, is ‘Looking forward to the next trip!’

Canterbury’s Elizabethan Bridewell, formerly the Poor Priests’ Hospital, recently the Canterbury Heritage Museum.

Turning to the Kent history postgraduates at CCCU, we had our first meeting of 2018 on Wednesday when the people leading the seminar were Kevin Field and Lily Hawker-Yates. Kevin is working on the workhouses of the New Poor Law Unions in rural east Kent, especially those of Blean, Bridge and Eastry, and he was keen to discuss with the group his findings regarding healthcare provision. Having outlined how the system was intended to work through a partnership between the Relieving Officer and the Medical Officer for each district (a subdivision of the Union), Kevin described some of the problems these Unions experienced in the early 1840s. These included men with no medical qualifications who applied to be Medical Officers, others who did not reside in the district for which they were responsible, those who neglected their duties, or worse, those who abused those in their care.

One of the issues he sought to raise was the problem of trying to ascertain the realities of medical and healthcare provision when his principal sources are the minute books of the Board of Guardians who generally had a vested interest in keeping the system going at minimum cost. This is not to say that some Guardians did feel they had a social duty to those locally who had been disadvantaged through no fault of their own, but such Guardians were seemingly in a minority. Yet some people were prepared to tell their stories to the local newspapers, such as the sad case of John Moyes whose son alerted the paper to the apparent neglect of his father in the month or so before his death. The inquest jury in this case were not happy about the treatment old John had received either, but most seem to have accepted the coroner’s verdict, albeit with considerable reservations. And it was this contrast between these narratives that Kevin drew attention to, and how they might be deployed by the historian to examine attitudes towards the professionalization of medicine, communal responses both inside and outside the workhouse, and rural-urban relations and differences.

The Old Poor House, Charing

Lily provided our second topic and she demonstrated ‘Viewshed Analysis’, which she is beginning to explore as a possible analytical tool in her investigation of how medieval people saw prehistoric burial mounds. As a research method I must admit I had not come across it before, but the idea of using GIS mapping and Lidar to assess what can be seen from a landscape feature and conversely where that same feature can be seen from sounds potentially very interesting regarding studies of the historic landscape. As Lily said, actually commissioning a Lidar survey is extremely expensive but such surveys are gradually being undertaken across the country for various water boards – interested in river valleys and the coast, and Historic England, as well as for local archaeological societies and units.

From Lily’s perspective, a landscape study of Bartlow in Cambridgeshire, conducted in 2009, that examined how, or if at all, certain barrows would have been seen from the main Roman roads in the area and a trackway that crossed the landscape between these roads, looks to be a promising model for her work on Kent. For the Cambridgeshire study found that the barrows would only have been visible from the trackway, not the roads, and from this they concluded that in this Roman landscape the location and size of these mounds was intended by local elites to impress their power and authority on the local population, rather than on a wider audience of those using the long-distance routes.

Lily has yet to finalise which barrows in Kent she will focus on to test this research method and during the ensuing discussion various ideas and locations were put forward, not least the feasibility of undertaking such an investigation for a coastal cliff-top barrow, as well as one or two in river valleys. Kevin’s presentation, too, sparked considerable discussion, suggesting the value of such seminars for CCCU’s Kent History postgraduates.

Stukeley’s engraving (1724) of Juliberrie’s Grave, Chilham [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Julliberrie%27s_Grave#/media/File:Stukeley%27s_picture_of_Julliberrie%27s_Grave.jpg]

Next week it is the Annual Becket Lecture on Tuesday in the large Powell lecture theatre at 6pm with, I believe, a wine reception beforehand. Dr Marie-Pierre Gelin (UCL) will be speaking on ‘Thomas Becket and his Predecessors at Canterbury’. This is an open lecture, all are welcome to attend free of charge –STOP PRESS this lecture has had to be cancelled because the speaker is unwell, further details in due course if it can be rescheduled for. later in the term. Then on Thursday it is the first lecture of 2018 organised jointly by the Centre and the Friends of Canterbury Archaeological Trust [FCAT]. This will be in Newton, Ng07 at 7pm when Ross Lane of Canterbury Archaeological Trust [CAT] will highlight the exciting archaeological discoveries the Trust has made at St Alban’s Cathedral in the medieval abbey’s cemetery, again all welcome and free for students. Finally, the same night and for the Canterbury branch of the Historical Association, Dr David Hitchcock (CCCU) will be speaking at 7pm in Canterbury Cathedral Archives on ‘Being female and homeless in early modern England’, again all welcome and free for students – a surfeit of riches!

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 1400

1400