The 68th International Sachsenymposion is drawing to a close today after four and a half days of guided tours, workshops, poster displays, a public lecture, and academic debate following a plethora of high-quality academic papers on a wide range of early medieval ‘Saxon’ topics.

Moreover, there was the conference dinner last night in the precincts of Canterbury Cathedral that followed the mayoral reception at the Beaney where Canterbury’s Lord Mayor welcomed the many conference delegates, the conference’s organising committee, headed by Dr Andrew Richardson, others who had been involved in delivering the guided visits, including Jon Iveson from Dover Museum, and representatives from archaeological, historical and heritage organisations across Canterbury. Canterbury Christ Church was well represented last night because I was in the company of Dr Andy Seaman, who lectures in archaeology and is a member of this august company, and Dr Mike Bintley, who teaches Old English and Middle English literature, is also on the organising committee and has a special interest in Anglo-Saxon landscape.

Andrew Richardson and Paul Bennett at the Beaney.

In his short speech to the assembled company at dinner, Andrew was keen to thank his German friend who had done all the translating during all the conference preparations and on the various tours, in addition to several members of Canterbury Archaeological Trust, especially Annie Partridge, who had taken on so many of the various tasks required in the run-up to the conference and over the last few days, sentiments that were echoed by the delegates. Another who had contributed greatly, again beforehand and even more over last weekend was Professor Paul Bennett MBE. I’m assuming readers of the blog are well aware of Paul’s many roles, most particularly as the Director of Canterbury Archaeological Trust, but also as a visiting professor and great friend of this Centre at Christ Church.

Consequently, I now want to turn to Paul’s open lecture last Sunday that he gave to an almost packed lecture hall at the University of Kent, the main conference venue. Taking as his subject ‘Canterbury in Transition’, Paul took his audience through a whistle-stop tour of Canterbury and east Kent’s history from the late Iron Age to the consequences to Augustine’s arrival in 597, albeit he concentrated more particularly on the three hundred years after AD 300. Thus, he began by outlining the layout of Canterbury as an Iron Age provincial capital on both banks of the River Stour, and its transformation into first a Roman town and then an important provincial capital on the Gallic model with a growing number of great public buildings. Among the buildings he discussed were the temple and precincts, the baths, and early and later theatres, as well as the city wall and gates, especially the important double-entry Ridingate – the way to Dover and continental Europe.

Paul’s opening slide.

Using evidence garnered from archaeological excavations over many decades concerning building foundations, cemeteries, and roadways that have yielded evidence of pottery, metal ware, imprints of wheel ruts, and other artefacts, as well as skeletal remains, Paul painted a fascinating picture of Canterbury’s Roman heyday and its later decline. Two factors regarding the latter were particularly interesting: the rising water table that meant the western side of the city between the two branches of the Stour became uninhabitable, and the likelihood of plague outbreaks and the abandonment of customary burial practices. Where land was no longer inhabited, it appears to have been used as pasture, while evidence for the latter phenomenon comes from archaeological excavations by Trust staff. For example, they have found evidence of bodies either dumped on the ground and only later buried in a long trench or bodies thrown into an open pit, the latter included the skeleton of a medium sized dog – the family pet that remained with its family in death as it had been in life.

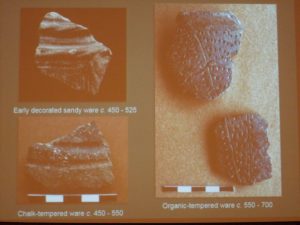

Other changes in this late 4th/early 5th century period that Paul discussed were the shift to timber-framed buildings constructed within the shell of earlier masonry town houses and the continuing decay of the great Roman public buildings, but also evidence of continuing trade – coins, pottery and metalwork, including military-style buckles that Paul thinks could denote the presence of local militia, just as occurred in Libya. So, yes, there are vast quantities of black loam across much of Canterbury in the archaeological record for the latter part of this period possibly indicating very little activity, but equally Paul pointed to the continuing presence of the roads that meant Canterbury remained at the centre of this wheel hub, as well as early Anglo-Saxon ceramics, including slightly later the possible presence of a Canterbury potter by AD 600. Yet intriguingly, albeit there is evidence from the late 5th century of a considerable number of sunken- featured buildings, great halls like those discovered over the last few years at Lyminge are seemingly missing from Canterbury.

Dating from the pottery offers important clues about the city’s history

Nevertheless, even if such archaeological evidence is absent for Canterbury as a royal centre in the way seen as Lyminge, and presumably also at Eastry and Sturry (see also Paul Cullen’s place name evidence in Early Medieval Kent, 800–1220), the documentary record, as the late Professor Nicholas Brooks believed, does point to Canterbury’s importance in the kingdom of Kent. Furthermore, even though some of the Roman street pattern disappeared within the walls, outside the Roman roads remained and inside the wall new streets were cut to form the first Anglo-Saxon street grid. Nor was this confined to the streets and the Roman city gate hierarchy changed to accommodate the new conditions, Ridingate losing its supremacy.

Finally, there is the significance of Roman Christianity on Canterbury’s history. For, even though the Chr-rho monograms on the silver spoons found outside Canterbury’s London gate among the hoard dated to the early 5th century demonstrate the likely of Christianity in the area at that time, the arrival of Augustine and his followers began a new chapter in England’s Christian history. As Paul pointed out, there is much in the fossilised fabric of St Martin’s church that shows what the early church of Bertha and her bishop would have looked like before Augustine’s arrival and then its subsequent development, in addition to first the monastic church of St Peter and St Paul and then Christ Church cathedral. In addition, Paul was keen to highlight the importance of these churches as the sites of 7th-century archiepiscopal and royal tombs, the use of imported and thus presumably expensive building stone, all pointers towards the role and place of Canterbury in the Anglo-Saxon world of Bede, that great early writer on what might be called the history of the English nation.

Paul demonstrates the importance of St Augustine’s Abbey

Drawing his lecture to a close, Paul reminded his audience that even though much was now known about Canterbury’s history during this formative period, there are still plenty of unanswered questions. However, hopefully at least some of these will be answered as a result of the new excavation off St Margaret’s Street at Slatters Hotel that should have started already but has been held up once again. Thus ended a splendid lecture, and Dr David Shaw, the chairman of the Trust’s trustees, thanked Paul on the audience’s behalf and, even though, there wasn’t time for questions, several people headed down to ask Paul for further details on particular matters.

Finally, an item of very recent news, the Centre is delighted to learn that Helen Castor will be coming again to speak at the Medieval Canterbury Weekend in 2018 and her topic next year will be Joan of Arc, but more news about the Weekend very shortly.

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 920

920