This week Dr Sheila Sweetinburgh has kindly suggested I write the blog report on what was for many of us a very exciting event. On Friday, we welcomed Professor Sandy Heslop to the Centre for Kent Heritage and History here at CCCU.

Sandy came down from University of East Anglia where he is Professor of the Visual Arts. Besides being President of the British Archaeological Society Sandy is also the lead on the Leverhulme-funded project on the 58 Medieval Parish Churches of Norwich https://norwichmedievalchurches.org/theproject/ . Sandy is very much an Anselm enthusiast and expert and he has published widely on the saint and Canterbury Cathedral, so it was a great pleasure to welcome him again to Canterbury to discuss St Anselm’s Crypt. It was excellent that the HLF Canterbury Journey team, Jan Leandro and Sarah Turner, with Head of Conservation Heather Newton arranged for the lecture to take place in the Cathedral Precincts AV Theatre so we could then explore the crypt following Sandy’s talk. Accordingly, it was in a packed room on Friday evening where the eager audience awaited Sandy’s free lecture on ‘The Organisation and Formation of St Anselm’s Crypt’.

Sandy Heslop and the Centre’s new banner.

Sandy began by setting St Anselm’s crypt in context. Not all English cathedrals and abbeys constructed between 1070 and 1120 have crypts; for example, Lincoln, Reading, and St Albans lack crypts. The percentage of great churches with crypts in England is about 35% – and all those with crypts were begun before 1100 (such as St Augustine’s Abbey, St Paul’s in London, Winchester, Worcester, York, Gloucester, and Bury). This dating allows St Anselm’s crypt (which was constructed between 1097 – an important date – and 1100) to be designated the latest – and as Sandy pointed out – the best. After St Anselm constructed his Canterbury Cathedral crypt it was as if everyone thought ‘we cannot better that’ and channelled their church-building mania in other directions.

Influences for Canterbury Cathedral’s huge undercroft may have come not only from St Augustine’s Abbey but also from old St Peter’s in Rome and from Pavia (S. Pietro in Ciel-d-oro). This Roman connection is important, and it might not be coincidence that Lanfranc was originally from Pavia, while St Anselm came from a wealthy and aristocratic family in Aosta in Northern Italy and visited Rome in 1070-71.

The main issue Sandy addressed was ‘Why build a crypt?’ After all they are not essential and great churches function perfectly well without them. Furthermore, such places can be – as semi-underground spaces often are – damp (or even flooded in the case of Winchester) and dark or at least poorly-lit. In answering his question, Sandy put forward several reasons why St Anselm wanted a crypt at Canterbury.

Canterbury Cathedral crypt

Firstly; entering the dark crypt space is a return to the earth and a reminder of our mortality. In turn, the exit from a crypt is a re-entry into the world of light. Any procession, pilgrimage or simple walk into and out of the crypt is a metaphorical journey of redemption.

Secondly, the semi-underground crypt allowed the quire above to be raised which has two benefits. It means one travels up to the High Altar from the nave, a raising up which brings you closer to God. The raised level in the quire also benefits the sightlines for viewing the quire’s stained-glass (and avoids a deep crick in the neck). Sandy pointed out most cogently that while the crypt had to be constructed first, the initial design for the whole east end of the Cathedral was considered from the top down – like the canopy of a tree, the trunk and the roots. For example, where the buttresses are placed in the foundations affects the positioning and size of the windows.

Thirdly; the crypt space enlarged the cathedral space. St Anselm carefully linked the crypt space to Lanfranc’s church by using the square root measure. The added floor space permitted more chapels to be constructed in the main crypt itself and in additional transepts. Sandy has calculated there were twelve altars in the upper church space and a second twelve in the undercroft in addition to the High Altar and – in the crypt – the altar to the Blessed Virgin Mary. These two sets of twelve altars would have represented the prophets and the apostles, the same number as in old St Peter’s in Rome. Every monk-priest would have been able to say a mass at a Cathedral altar every day.

In addition, Sandy mentioned the date of construction was important. 1097 was the five hundredth anniversary of St Augustine’s arrival in Kent as a missionary from Pope Gregory the Great in Rome. Thus, again this underlines the link between Rome and Canterbury, which he feels in one of the key issues in the crypt’s form and construction.

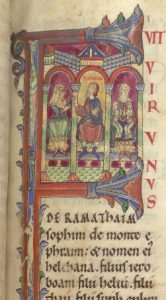

Illumination from the Rochester Bible

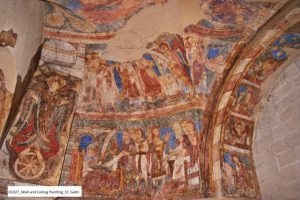

The crypt space itself was as elaborately decorated as the church above. The wall-paintings preserved in St Gabriel’s Chapel in the crypt attest to the fine craftsmanship of the artists. Sandy showed correspondences in the wall paintings to the Rochester Bible of c. 1120, in terms of the figures’ proportions, linen folds, and characteristics such as the positioning of the hands.

Wall paintings – St Gabriel’s chapel

The crypt capitals and shafts are among the finest Romanesque sculpture in existence with an ambitious programme of designs that start with quiet designs such as carved heads and riders and build to a crescendo of human imagination full of hybrids before plain capitals immediately in front of the Altar to Mary – emphasising the power and majesty of Divine Creation. The pillars were just as colourful as the wall-paintings and there are still slight traces of colour if you look closely. Sandy concluded by saying that the crypt was conceived as a fully-functioning part of the cathedral, and should be seen as one of the glories of Canterbury Cathedral. Following his lecture members of the audience were keen to ask questions, and he answered several before proceedings were brought to a close so that the audience could visit the crypt to see the stone carvings he had discussed in his lecture.

In order to provide everyone with a chance to look at the crypt capitals in subdued light – the closest one might come to what the monks would have experienced when the crypt was constructed, the audience was divided into three groups who were guided between the central area of the crypt, and the chapels of St Gabriel and Holy Innocents. This guiding was done by the cathedral team of Jan, Sarah and Heather, and stationed in the two chapels were Sheila (Holy Innocents) and Dr Emily Guerry in St Gabriel’s. Emily is an art historian and lecturer at the University of Kent and an expert on the Sainte Chapelle. Meanwhile I was in the central area of the crypt where there is an amazing variety of forms from warriors to lions to eagles and snakes.

One of the Canterbury Cathedral crypt capitals.

The people on each of the three tours were full of interesting questions and viewpoints, and for many this was the first time they had really looked at the carvings. Moreover, many appreciated how those stationed around the crypt discussed such matters as how the capitals were produced, how some of the beasts might bear allusions to the Bible and other medieval didactic texts, and how the symbolism associated with the beasts might have been used by the monks in their personal meditations as they sought become better Christians. Like any reciprocal process, the discussions were two-way and I think everyone took away new ideas as we trooped out of the crypt after an hour, which had actually seemed to go far faster than that. Indeed, people still wanted to talk about what they had seen even as we left the precincts, and this excitement about what they had discovered works well with the ideas of a lack of ‘closure’ evidenced in the unfinished capital, as well as ideas on conflict which might point to aiming towards reconciliation. Finally, it is worth noting that the torchlight on the capitals made these beautiful carvings spring to life – an exciting bonus for all. My thanks to everyone for making this such a splendid event, I do hope more will follow.

DEH

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 1597

1597