Keeping with the theme from last week of activities of those involved directly or indirectly with the Centre in ‘history in the community’, this week I’ll focus on the Kent History Federation’s one-day conference at Sandwich, before mentioning Dr Diane Heath and medieval animals.

As an itinerant conference, Sandwich Local History Society hosted it this year and participants from local history societies across Kent gathered in the Sandwich Guildhall for a packed day of lectures and guided tours (next year it will be the Centre at Canterbury Christ Church on Saturday 12 April). Even though 20 May does not mark the actual 800th anniversary to the day of the battle of Sandwich (although it does for the battle of Lincoln), this naval engagement featured heavily in the programme. So too did Magna Carta. Firstly, what came before regarding the baronial conflict of John’s reign that was not resolved until his son’s early years as king. Then after: the defeat of the French that meant the continuation of the Plantagenet kings who found themselves having to reissue Magna Carta in an attempt to secure taxation to engage in various theatres of war, which formed part of the case Dr Sophie Ambler made respecting the creation of English identity.

The Sandwich mayoral party.

However, I am jumping the gun somewhat. Thus I’ll bring us back to the warm welcome speakers and audience received from the Mayor and Mayoress of Sandwich, and Richard and Jacqui Linning and their colleagues from the Sandwich Local History Society, the proceedings opened by Mrs Jackie Grebby, Chairman of the Kent History Federation and Lord Boyce, the Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports (by video link). After refreshments, all assembled in the hall to hear the first two speakers: Richard Brooks and Sophie Ambler. Sophie is my indirect link to the Canterbury Centre because she worked on the AHRC-funded project on Magna Carta with the Centre’s Professor Louise Wilkinson. What these two lectures had in common was that they both explored the battle of Sandwich, Richard, in particular, in considerable detail which was fascinating. Nevertheless, rather than give you a summary I’m going to tackle this differently. Indeed, if you want to learn about the battle you can consult Richard’s book, The Knight who Saved England: William Marshal and the French Invasion, 1217 (Osprey, 2014).

Instead, what I want to take as the common theme running throughout all the talks is the relationship between ‘imaginative memory’ and communal identity. Amy Remensnyder coined this term when she was examining institutional identity among early medieval European monasteries. From her analysis, she saw the fashioning of foundation legends by these houses as a complex process that drew on the ‘social memory’ of the institution. The community looked back to “a glorious past” through the creation of a shared institutional identity, whose very antiquity, as described in the legend, provided authority for those living in the present. Now, this deployment of antiquity will become more evident further down, but the concept of ‘imaginative memory’ is also applicable within a shorter timeframe without resorting to what seems to be the present mantra of ‘fake news’. Nor do I want to use what might be seen as the equally unhelpful, and in 13th-century terms ahistorical word propaganda, because, as Remensnyder says, those constructing the legends (narratives) “believed in them at some level” – memory mattered.

Richard Brooks discusses the battle of Sandwich.

Such an idea, and the necessary process of constructing a narrative, became evident during Richard and Sophie’s lectures, because both were to a degree looking at the production of competing near contemporary texts about the creation of national heroes. Not that Sandwich was the only decisive battle (and there were other major twists and turns politically as well as militarily in the early 13th century), but it was the final crucial engagement and stopped any ‘regime change’ in its tracks, thereby ensuring a continuing ‘English’ monarchy and the central place in history of Magna Carta. As Richard discussed, there are a surprising number of almost contemporary accounts of events during and around 1217, and some of these offer considerable detail about the battle itself. One of these is The History of William the Marshal, a long poem composed at the instigation of William’s heirs very soon after his death. Using this, as well as the other sources, Richard believes William Marshal was “the true hero of Sandwich” because he was able to rally the English mariners, including those from the Cinque Ports, to defend the Channel against the French fleet and without a naval force there would have been no battle!

Sophie Ambler examines the illustrations of the battle in Matthew Paris.

Richard also mentioned the detailed account of the battle in Matthew Paris’ Chronicle, and how we see for the first time a reference to ‘luffing’ as a nautical term, but it is Sophie’s exploration of the Chronicle that I want to pick up on. She began by explaining that Matthew Paris had initially used the chronicle of Roger of Wendover, his predecessor at St Alban’s Abbey, in his own account. However, in the mid-1230s she believes the manuscript evidence indicates that Hubert de Burgh, sheriff of Kent and castellan of Dover in 1217, relayed his memories of events that year to the monk, especially those relating to the battle of Sandwich when he was the English naval commander. Thus, just like the History, which drew on the memories of William Marshal’s family and comrades, as well as their recollections of what William had said about past events and his place within them, Matthew’s Chronicle was mediated through the lens of Hubert de Burgh’s memory and the monk’s own response to the story. Furthermore, writers, in looking back, also look forward, as well as taking account of the present, and this complex compositional process is all the more interesting when one considers that such narratives drive and are driven by ideas about identity – individual, communal, national. Consequently, the first speakers, as well as providing fascinating ideas about the events of 1217 and especially the battle of Sandwich, provided the audience with interesting ideas about how contemporaries envisaged critical events and the men who shaped early 13th-century English history.

Dr Mark Bateson, the finder of Sandwich’s Magna Carta at the Kent Library and Archive Centre, Maidstone.

After the second refreshment break, three speakers looked at different aspects of Sandwich and Cinque Port history, and after lunch Linda Elliott, Honorary Sandwich Archivist, highlighted some of the gems in the town’s archive (and museum), including Edward I’s Magna Carta and Charter of the Forest, and Sandwich’s Custumal (a later version of the lost original of 1301). Of the later morning speakers, Ian Russell, Registrar and Seneschal of the Confederation of the Cinque Ports provided a summary of the role of the Cinque Portsmen as the English navy of their day – from perhaps Edward the Confessor to the Spanish Armada. In particular, he set out the rights and privileges given by the Crown and the provision of Ship Service that was expected of the Ports in return (Edward I’s General Charter in 1278). However, the Portsmen sometimes put their collective interests before their duty to the Crown, including piracy on their own account. I followed Ian, offering a brief chronological history of Sandwich’s four medieval hospitals: starting with the leper house at Eche End (later known at St Anthony’s hospital) and finishing with Thomas Ely’s almshouse – St Thomas’ hospital. Finally, John Henderson, the chairman of Sandwich Local History Society, provided a whistle-stop tour through Sandwich’s history from the arrival of St Wilfred in AD 664 to the Second World War, which included the arrival of Henry III’s elephant (see 7 May blog) and its encounter with a bull at Wingham where the elephant was triumphant.

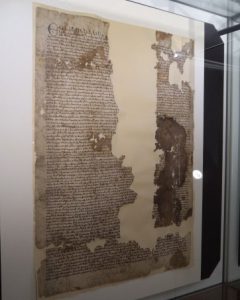

Sandwich’s Magna Carta – now on display in the Guildhall Museum.

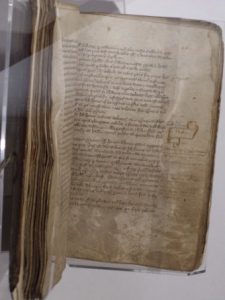

Keeping with the earlier theme of social memory, the construction of corporate narrative and identity, and the Sandwich battle of 1217, the thread running through these four lectures can be illustrated using the town’s early 14th-century custumal and a contemporary chronicle. A century after the battle, for the men of Sandwich it was the role of their ancestors, and those of their co-barons from the other Ports that mattered, not William Marshal or Hubert de Burgh. In this reworked locally accepted version, as seen in the History of John of Canterbury, the points highlighted were: the crucial place of the Portsmen in the battle; the consequent foundation and maintenance by the men of Sandwich of St Bartholomew’s hospital and chapel for the benefit of the town by housing the aged poor; and the desire to commemorate annually Sandwich’s deliverance. Such indirectly produced local knowledge was important, but the authoritative voice of the civic authorities, as mediated through the section of Adam Champney’s town custumal that covers St Bartholomew’s hospital begins with the annual procession on the saint’s feast day: 24th August (and the date on which the battle took place). Moreover, this detailed description of the commemorative ritual makes no mention of the battle, for that was presumably no longer viewed as strictly necessary. Instead the authentic text focuses on the relationship between the civic officers, their ancestors and successors, and the town’s saint in his hospital, demonstrated through the use of objects – tapers donated by the mayor and jurats to St Bartholomew – and the route of the procession – from St Peter’s church at the centre of the town (the advowson held jointly by the civic authorities and St Augustine’s abbey, the site of certain civic elections and town courts) to the hospital beyond the town walls. Thus for the men of Sandwich, the Portsmen generally, the Crown and other audiences, events in 1217 that might be seen to include the earlier and later issuing of Magna Carta, were articulated by the early 14th century through the custumal – the processional ritual and associated myth, whereby civic identity was bound up in ideas of patronage, authority, responsibility, charity, power, and above all that they were God’s people – St Bartholomew was and would continue to be with them as protector and advocate.

The mid 15th-century Sandwich custumal – on display in the Guildhall Museum

Dr Peter Rowe, as President of the Kent History Federation, thanked the organisers and the various speakers for their very interesting lectures. After the generous hospitality provided at lunchtime and the refreshment breaks, participants set off on the wide choice of guided tours that the organisers had laid on. These, too, seem to have been popular, as was the bookstall of Sandwich publications and Richard Brooks’ book. Consequently, the organising committee should be congratulated on a first-rate day.

British Library: Royal 12 FXIII, f. 10v – note ‘smug’ unicorn even as it is speared.

Before I end this week, I thought I would mention another member of the Centre. Diane Heath gave a lecture to about thirty people from the Bridge and District History Society in which she talked about the medieval beasts to be found in the Medieval Bestiary. She began by looking at lions, tigers and bears, following this up with the enigma of the Leucrota and then moved on to the monstrous hybrids, such as the sirens, onocentaurs, dragons and unicorns. She ended by considering the living rock – the Oyster and its lovely pearl! As she explained to her fascinated audience, she had been talking about animals, but for the monastic medieval audience these animals should be envisaged in terms of humans, their failings and their strengths, set within a theological framework to instruct different audiences who had varying levels of spiritual understanding. Thus, the honey trap of the maiden (see above) catches the unicorn, from the ‘Rochester Bestiary’, an episode understood as a figure for the Blessed Virgin Mary and Christ.

This leads me to my final comment that Diane and I will be meeting the ‘Canterbury Journey’ people tomorrow to take forward the project Diane wants to do regarding using lasers to ‘colour’ the animals of the cathedral crypt. This project will be helped financially by the CCCU Knowledge Exchange Award that the Centre won earlier in the year for its Medieval Canterbury Weekend project – a very fitting use of the prize, and I’ll report on the outcome of the meeting next week.

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 1283

1283