As the week before teaching officially commences, this has been a week of meetings for Freshers Week as well as other activities linked in various ways to the Centre. For example, Dr Diane Heath and I used her quiz based on Bethany Brown’s internship work on the St Mildred’s church and parish history posters for the new BA History and Medieval & Early Modern History Studies students.

Other meetings have included the Gough Map project involving some of the regional contributors and some of the specialists, such as those working on place names or medieval mapping techniques; as well as a meeting with one of the Centre’s external partners, the Friends of Canterbury Archaeological Trust [FCAT]. Among the latter’s agenda items was Professor Paul Bennett’s retirement event, as Director of Canterbury Archaeological Trust, that has had to be amended due to the new government restrictions. Nevertheless, there are plans afoot to try to make it as inclusive as possible and I hope to bring you more on this in a week or so.

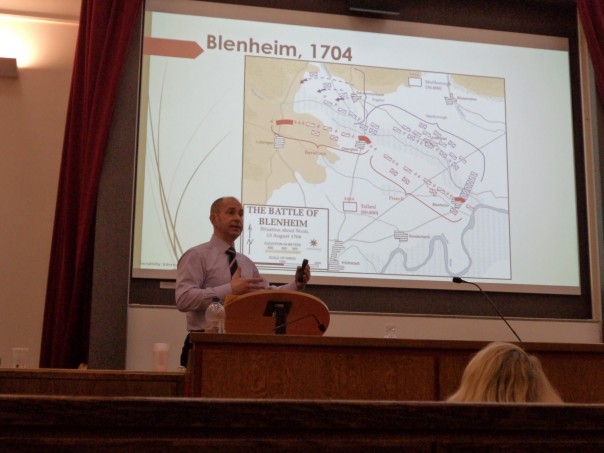

Additionally, Diane, Dr Claire Bartram and I at the Centre have been busy preparing for teaching, and there is also more news on the virtual Tudors and Stuarts History Weekend, due to take place on Saturday 27 and Sunday 28 March 2021. Among our speakers, I am delighted to say will be Professor Keith McLay, formerly one of the Faculty Deans at CCCU and now Pro-Vice-Chancellor at the University of Derby. Some of you may remember his fascinating lecture on Marlborough’s campaigns at the Tudors and Stuarts Weekend 2019 and I’m sure 2021 will be equally excellent. We will also be welcoming, albeit remotely, Dr Onyeka Nubia of the University of Nottingham, and it will be great to hear him speak on an aspect of his research into Black Britons and cultural identity. As soon as I know the full programme, I’ll let you know and then again when Matthew Crockatt and Kellie Hogben have done their usual sterling work of setting everything up on the Centre’s History Weekend webpages.

But to return to reporting on this week, the Kent History Postgraduates decided they would try a new development at their meeting this time. We began by welcoming back Jacie Cole on her return to researching her doctorate, and congratulating Dr Lily Hawker-Yates on having accomplished hers, although, as she said, quite whether graduation will take place in January is somewhat of a moot point – she is going to wait for an actual rather than a virtual ceremony! Also, although this took place at the end rather than the beginning, I’ll just record that Janet mentioned that she had visited the ruins of Lesnes Abbey recently. In addition to the ruins, the monastic fishpond survives, now a lake, and even though somewhat faded, she had been impressed by the signboards around the site as a means to explain to visitors something about the abbey’s history. Of course, this has a particular resonance for the group because Lesnes Abbey is one of the three monastic houses that Jane Richardson is studying for her doctorate because all three were casualties of Wolsey’s ‘Little Dissolution’.

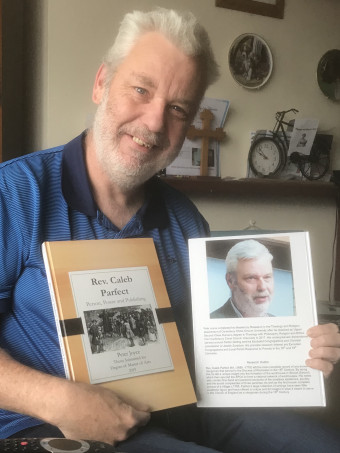

This takes me to the main part of the meeting where we had our first online presentation by one of the group, and because Peter Joyce has recently gained his Masters by Research, it was wholly appropriate that we heard from him. As Peter said, he is keen to explore ‘history from below’ from an ecclesiastical perspective, and by investigating the life and writings of the Rev. Caleb Parfect, he has found a rich seam concerning examining communities through the eyes of those who served them. Furthermore, north-west Kent has been much neglected as an area of research to a large extent and Peter is keen to put this right because even though the sources generally are limited for such parish and cathedral clergy – their papers almost always burnt after their death – in Parfect’s case, perhaps uniquely, they have survived.

Although Peter has given presentations to the group before, having now completed his Masters he is in a better position to take a step back and view Parfect’s career and writings within a broader framework. So who was Caleb Parfect? Hailing from Somerset and the son of a weaver, he was a man of humble origins who when he went to Balliol College in 1709 seems to have gone there as a servitor. But our man had ambitions and having gained a university education, like many other of the time, the Anglican Church beckoned, and he was ordained as a deacon in 1710 and as a priest in 1716. He was also a committed Anglican Christian who wished to undertake godly service and his chance came 3 years later when he arrived in Kent to take up the living at Strood in the diocese of Rochester. A year later came the living at Cuxton, and from 1733 he served as the parish priest at Shorne, as well as being a minor canon at Rochester Cathedral, remaining there until his death in 1770.

In addition to these various communities that he served, he was a busy family man, marrying first Bennett Walsall with whom he had four children, although the birth of the last killed her and their baby daughter soon followed her mother to the grave. This marriage had set Caleb up because his father-in-law was John Walsall, a very influential Rochester attorney. His second marriage took him even higher up the social ladder because his new wife was Bridget Poley the granddaughter of Sir Richard Head, and a mark of his increasing status locally can be seen by his aristocratic patron of the Shorne living allowing her young daughter to stay in the Parfect household, a mark that he had indeed ‘made it’ into genteel society.

Moreover, the work and energy he put into his family and networking was matched by his activities regarding his writings and his actions on behalf of the communities he served. His large personal archive of letters and notes, as well as his 7 books, have given Peter a unique opportunity to conduct a case study on the man and his parishes, as well as the Rochester Cathedral community and diocese more broadly.

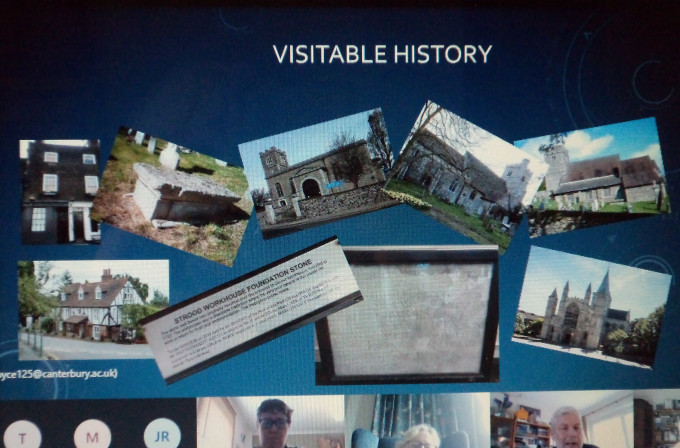

I’m just going to touch on a couple of the examples Peter provided because they are linked to Parfect’s ideas on baptism, burial and caring for ‘his people’. But first, it is important to note that his pamphlet proposing the need to set up a workhouse in Strood in 1720, ie pre-dating Knatchbull’s 1723 Workhouse Test Act, shows the calibre of the man. Moreover, through his workhouse and the founding of the SPCK he believed he was doing God’s work, the workhouse, while providing to some degree for the poor of the parish, was even more a money-making concern for overseas missionary work through the SPCK, and was controlled by the vestry. The vestry, comprising the ‘great and the good’ of the parish, thus had oversight of parochial charity, the workhouse and out relief for other groups within the local poor.

Turning to his responses to ideas about baptism, as Peter said, Parfect believed in the establish Anglican Church and state working together, but he was prepared on occasion to temper this stance for the wellbeing of members of the local community. Consequently, he was against those from the higher echelons of society who wanted to have private baptism for their children believing instead that they should take place within the public act of worship. Nevertheless, he was prepared to baptise a child that could not be buried because it had not been baptised, which was a major relief and comfort for the Bolting family.

Equally, he was prepared to help families where a family member had committed suicide. The example Peter gave concerned William Tomlin from a well-established local family of tanners who had hanged himself in the local pub. As a case of suicide, William was not allowed by the Anglican Church to be buried in consecrated ground – something that was not changed officially until 1960. However, such a disgrace would have destroyed the family and to overcome this it was essential to help the coroner to come to the right verdict. Such coroner’s courts were held in the local pub and thus it was necessary to get to him immediately, offer sufficient incentive, and bring forward the necessary witnesses which would mean that he could pronounce a verdict of the deceased having been a lunatic prior to his death – being of unsound mind meant he was no longer seen as responsible for his actions. As a result, Parfect was able to ensure Tomlin could indeed be buried in the churchyard, thereby bringing some comfort to the family.

Such examples, and other matters in the parish records, as well as in Parfect’s own archive have given Peter many insights into the history of this part of Kent during the long 18th century. Furthermore, Peter has uncovered far more sources that have yet to be investigated and it would be excellent having completed such a pilot study for him to take this further in the future to complete his doctorate. However, in the meantime, as people suggested, it would be great if Peter decided to use material from his MA thesis to write an article for Archaeologia Cantiana, because of the important insights he has uncovered.

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 1523

1523