Next week will bring the first Chatham Historic Dockyard conference at which Dr Martin Watts (CCCU lecturer and member of the Centre) will be speaking on ‘Chatham Dockyard at the heart of industry and sea power’, and I’ll hope to have some information about this event from Martin after next Friday.

Keeping with the nautical theme, I had a meeting with Stuart Bligh and Dr Elizabeth Edwards yesterday morning concerning a ‘Maritime Kent through the Ages’ conference next June that we at the Centre will be holding in conjunction with the Royal Museums Greenwich and Kent Archaeological Society. This is preparatory to producing a collection of essays under the same theme, which seems wholly appropriate for a county surrounded on three sides by sea!

‘Bridge Works’ exhibition – building the 1391 bridge.

The sea will also feature at the Medieval Canterbury Weekend next April because among the many excellent speakers is Imogen Corrigan who will be looking at medieval perceptions of the sea and its many perils. Whether boats will feature in Dr Emily Guerry’s lecture at the Weekend, I’m not sure. However, the acquiring of relics from the Middle East, a fascinating topic in its own right, did necessitate their transport to western Christendom, specifically in the case Emily will discuss, to the Sainte-Chapelle that was intended to glorify the Crown of Thorns and by inference the French monarchy. If either of these sounds interesting, why not check out the Weekend’s webpages at: www.canterbury.ac.uk/medieval-canterbury

Elizabeth I’s Deed of Corfirmation, 1588.

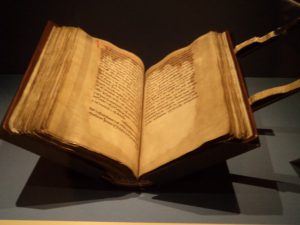

Still staying with water, albeit the River Medway rather than the sea per se, last Wednesday evening I attended the official opening of the ‘Bridge Works’ exhibition in the undercroft of Rochester Cathedral. This collaboration between The Rochester Bridge Trust and Rochester Cathedral has produced an excellent exhibition where you can see fascinating material on Rochester Bridge from the wooden Roman bridge on its stone pillars up to the fifth and newest bridge that was opened in 1970. The exhibition also features how the bridge was organised regarding issues such as ongoing maintenance, and if and when a new bridge should be constructed. For centuries, and even today the system has been modified rather than dismantled, the bridge was cared for corporately, almost as you would a small town, with a Court of Wardens and Assistants who were elected from the parishes that contributed to the bridge’s wellbeing. This communalty of the bridge is enshrined in the Letters Patent of Richard II from 1399 and the Deed of Confirmation of Queen Elizabeth I in the year of the Spanish Aranda but has its roots in an even older document. For among the texts to be found in Textus Roffensis, two books bound together in the 14th century, is the Bridgework List in Old English that tells who was responsible for maintaining the bridge, a reminder that the bridge was extremely important even before the coming of William the Conqueror.

Textus Roffensis – showing the Bridgework List.

Even though Canterbury, too, is on a river, the Stour has never matched the Medway. Yet in medieval times there were wharves in Canterbury, as witnessed by a 15th-century will bequest where William Benet, Canterbury’s first mayor, donated 300 feet of ashlar Folkestone stone to make a wharf by the King’s Mill. Now today the King’s Mill is ASK pizza restaurant but in the late Middle Ages was the site of the public latrine, and even more importantly was on the opposite side of the city’s Eastbridge to the hospital dedicated to St Thomas the Martyr or St Thomas of Canterbury that accommodated poor pilgrims.

This medieval hospital still functions as an almshouse, and will feature again soon because the Centre is working with the Trustees there on a new exhibition, but for now I’ll turn to two events that took place on Thursday. Firstly, ‘The Canterbury Journey’ team held its first conference at Canterbury Cathedral on the Black Prince – I was there for the Centre chairing a session (the previous evening Dr Diane Heath had given a presentation on the cathedral crypt capitals) and it seemed to be a highly successful day from the general buzz around the place. Then in the evening the Centre, jointly with the Friends of Canterbury Archaeological Trust, welcomed Clive Bowley to talk to an appreciative audience on the city’s timber-framed buildings. I don’t have room this week for more than a few sentences, but he provided a fascinating assessment of those who had sought to preserve Canterbury’s buildings and those who had seen them as a hindrance to development and modernisation. Nevertheless, in 1990 Canterbury still possessed about 500 of these buildings, yet it was a sad diminution from the 1200 known to have been in the city in 1874.

Clive Bowley discusses collaboration with Canterbury Archaeological Trust.

During Clive’s many decades in Canterbury as both Canterbury City Council’s Conservation Officer and working in the private sector, he has seen many changes and he has built up a considerable archive of images showing buildings long since gone and the work of pioneers in what today we would call heritage. Among those he mentioned from the early 20th century were Powell, an antiques dealer whose activities included putting a timber front on Conquest House in Palace Street, and Walter Cozens and his son, another Walter. These Canterbury builders took a considerable interest in old buildings, buying and restoring them for new uses, and even moving them, as in the case of what became Canterbury’s baths, although this building was destroyed by bombing in WWII. Clive, himself, worked with the architect Anthony Swaine in the second half of the 20th century, a period that saw a mix of official destruction (post WWII up to the 1960s) and sympathetic, including grant-giving official responses (c.1970–c.2000). Much of the latter has coincided with Canterbury Archaeological Trust’s presence in the city (following pioneering work of several archaeologists working in the bomb-damaged city), and, as Clive recalled, he first worked with John Bowen from the Trust and more latterly most particularly with Rupert Austin, who continues to be one of the foremost experts on the city’s buildings.

Showing the detailed drawings of such buildings produced by CAT.

Finally, returning to the Kentish coast if not the sea, here is a short review by Michelle Crowther, Learning and Research Librarian for the School of Humanities and a lover of old newspapers, but sadly allergic to hops, of a book recently donated to the Centre (another copy in the CCCU library).

Drinking in Deal: Beer, Pubs and Temperance in an East Kent Town 1830-1914 by Andrew Sargeant, Deal: BooksEast, 2016. ISBN 978-1-908304-20-9 £25 (hbk), £20 (pbk).

An amazing array of bottles.

At 288 pages this is not a coffee-table read, neither is it a tedious list of pubs and publicans, but a lively social history of Deal, providing insights into the town’s past seen through a lens of brewing and beer drinking. With a five-page bibliography, appendix and a breadth of references from both newspaper and secondary sources, it is a well-researched tome, illustrated throughout and worthy of its place in any local studies collection.

The pages are jam-packed with interesting stories from the eleven-year old shop-lifter with a penchant for Dutch and Cheshire cheeses, the soldier ‘secreted’ in a bedroom, the angry wife who struck her husband with a ginger beer bottle and the prisoner who attempted to knee his way up a chimney. All cleverly linked to the demon drink and told in an engaging and entertaining way.

Yet these lurid accounts of lust, violence and larceny stand alongside heart-warming stories of wedding anniversary dinners, sea-bathing, holidays, ‘chops, steaks and teas’ (p.116) and the author’s intention seems not to create a sensational exposé of vice and drunkenness or a morality tale, but an affirmation of the positive contribution public houses have made to Deal’s history, both as places of conviviality and entertainment and as meeting places for societies. Who could fail to wonder about the meetings held by the ‘Scorched Bean Society’, the music played by the visiting German string band or the smoking concert held at the Crown? Then, there are the soft drinks – lithia, zolakone and potash – that have faded into the past along with the Temperance societies.

It is evident that Sargeant has done his research and his sources from borough minutes to parliamentary papers are clearly stated in his introduction, however, Sargeant freely admits “this book is above all an exercise in deploying evidence from local papers” (p. 12) and the Mercury and Telegram are often cited. This gives the book a colourful immediacy, and the town’s highs and lows are explored through the medium of newspaper reporting and beer.

With its visually exciting descriptions of the Walmer brewers rowing to victory in the Deal Regatta of 1864, to the reports of drunken brawls in the town’s pubs and taverns in the decades after, I hope that you will be intoxicated by this book as I have been. When I next visit Deal, I shall be looking for traces of the Deal Lugger, the Beehive, the Alhambra and the Hovelling Boat but if you want to know more, I suggest you read the book. To obtain a copy email BooksEast@btinernet.com or visit their website www.dealbookseast.co.uk

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 997

997