Last night a packed lecture theatre of students, staff and the public were treated to a great lecture by Paul Bennett, Visiting Professor of Archaeology in the Centre for Kent History and Heritage at CCCU, but I just want to mention another couple of things before I get to his talk.

For those of you following the UNESCO Heritage A – Z you will know that today we have got to ‘I’ and thus you can discover information about ‘Ivy’ by Peter Vujakovic. The entries for the previous days are also available on the website, so do please check out earlier letters if you are new to this: https://medium.com/the-christ-church-heritage-a-to-z

In addition, I would just like to say that there are still spaces available at the UNESCO Canterbury conference being held on Friday 24 and Saturday 25 May at Old Sessions, CCCU. Details of the programme and how to book are available at:

https://www.canterbury.ac.uk/unesco-canterbury or call 01227 78299. Among the speakers on that Friday will be Cressida Williams, Head of Canterbury Cathedral Archives and Library, while on Saturday speakers from CCCU will be Professors Jackie Eales and Peter Vujakovic and Drs Diane Heath and Ralph Norman. Indeed, this conference is bringing together Geography and History at CCCU, extremely important subjects in their own right but together a formidable combination as witnessed by Peter and Jackie’s work in bringing this conference to fruition.

Jackie Eales introduces Paul Bennett

Archaeology, too, is important, and before Jackie, as joint Director of the Centre, introduced Paul last night she mentioned that she has been working with Dr Jake Weekes (Canterbury Archaeological Trust) regarding a historic mapping project on Canterbury. This involves the production of both a new printed historic map of the city and a series of digital maps that effectively form a palimpsest, thereby drilling through 20 centuries of Canterbury’s topography to understand its development over time.

As Paul mentioned at the start of his lecture, Canterbury Archaeological Trust (CAT) has undertaken archaeological excavations and architectural surveys at all three parts of Canterbury’s UNESCO site, and it was this work over the last few decades that as Director of CAT that he wished to foreground in conjunction with the activities of various antiquarians and keen amateur archaeologists. Many of these had been clergymen, often associated with Canterbury Cathedral, who had explored different parts of St Martin’s church, St Augustine’s Abbey and Canterbury Cathedral and precincts in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Paul begins his lecture on Canterbury’s UNESCO World Heritage site

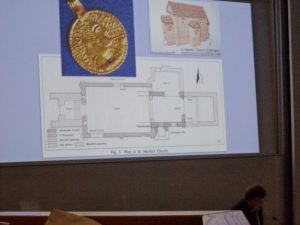

For his lecture, Paul decided to take a chronological institution by institution approach and so began with St Martin church. As he said, the ideas put forward in the Victorian era are still broadly viewed as right. Even though there is some uncertainty about the original building, Paul believes it was probably built around 580 for Bertha and her entourage when she came to marry Ethelbert before he became king, employing reused Roman building materials and techniques. The second phase to enlarge the church came post 597 when Augustine and his brethren needed somewhere to worship while the new (abbey) church dedicated to SS Peter and Paul was constructed on the site of the later St Augustine’s Abbey. To illustrate these early development phases, Paul discussed the different building materials deployed – local and from northern France; the type of mortar used – he has seen identical late Classical period mortars in Rome and North Africa, and the two doorways (firstly the wide one, then the narrow one) on the south side into the ‘chancel’. For those living in or near Canterbury it is well worth visiting the church and amongst these features you can see the reused Roman tomb slab that was used as a lintel for the first door.

Paul then turned his attention to the development of the nave, showing his audience the beautiful semi-circular buttress half way down the south side. Again he noted the employment of certain diagnostic building stones before exploring the west wall that can be seen from inside the church. Again early features are fossilised within the later structure, such as the early lancet windows that were considerably enlarged before the Norman Conquest. Initially there would have been three, but the central one was taken out when a much larger window was inserted in the 14th century before it too was infilled to form the late medieval church tower. As Paul said, this gem should be much better known and he encouraged his audience to visit the church and to spread this knowledge much further afield.

Paul shows what the original St Martin’s church may have looked like

He then moved to the development of the St Augustine’s Abbey site. As he said, when Augustine arrived in Canterbury it was probably a royal ville within what would become the cathedral precincts having only the beginnings of an early Anglo-Saxon road system, and what remained of the earlier city was still dominated by the ruins of the great Roman theatre. Just like St Martin’s church, our interpretation of the abbey site – both the inner and outer precincts, has until recently relied on the work of antiquarians and early 20th century archaeologists. However, for the outer precincts especially, the Trust under Alison Hicks has undertaken a tremendous amount of archaeological work as CCCU has and continues to develop its North Holmes campus. Consequently, as Paul demonstrated, we now know far more about the different medieval phases of work from the original 7th-century SS Peter and Paul church to Abbot Fyndon’s iconic early 14th-century gateway and the new service court by way of significant developments in the late Anglo-Saxon period, the time of the early Norman abbots, and further work in the 13th century. Moreover, even though the abbey buildings faced considerable difficulties following the Reformation in Henry VIII’s reign, its time as first a minor royal palace and later the residence of the Wootton family before becoming a place for cock fighting and similar pastimes, only to be ‘saved’ by becoming St Augustine’s Missionary College, part of the King’s School and Canterbury Christ Church University, with the main site under English Heritage.

Among the key issues Paul wished to highlight is the international importance of St Augustine’s as the burial place of the leader of this Gregorian mission and several of his followers, early archbishops and their contemporary royal patrons and supporters. In addition, although now lost some of the architectural features such as Abbot Wulfric II’s ‘Rotunda’ would have been marvels for those visiting the abbey in the 11th century. For some of these features we can only guess at their splendour but just a taste of these can be gained from the few fragments of carved stone that were reused following the abbey’s dissolution – as you can see from this photo.

Paul discusses the wonderful carvings that would have adorned the abbey church

Moving finally to Canterbury Cathedral, Paul noted that the original Anglo-Saxon church cut through Roman building foundations as well as dark earth deposits. This sense of discontinuity is important for thinking about 5th and 6th-century Canterbury. Using the remarkable findings from CAT’s nave floor and other archaeological excavations in the precincts in conjunction with the documentary sources, such as Eadmer’s and later monastic chronicles, Paul showed his audience a series of reconstructions illustrating how the cathedral had changed over the Middle Ages.

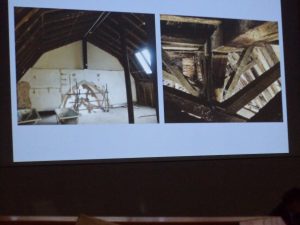

Not, of course, that the cathedral was the only important building in the medieval period, and Paul discussed the magnificent archiepiscopal great hall built by Hubert Walter and Stephen Langton in the early 13th century – second only to Westminster, as well as the great suit of buildings that comprised Christ Church Priory, including Lanfranc’s infirmary and the later Table Hall with its fantastic timber roof, dated to 1269. Sadly the latter was only exposed during the hall’s restoration and I had never seen a photo of it before – see below, although Paul has often mentioned it during our joint MA option course on ‘Medieval Canterbury’.

The great timber roof in Table Hall

Paul finished his examination of Canterbury’s UNESCO World Heritage site through an archaeologist’s eyes by looking at Christ Church Gate. He mentioned that when the new bollard was put in the Trust found evidence of the earlier gate from about 1200, and more recently CAT has been conducting architectural surveys on the existing early 16th-century gate, albeit much restored by Carrow in the 19th century, and on the later 17th-century great wooden doors as part of the HLF-funded ‘Canterbury Journey’ project.

After his fascinating lecture Paul received thunderous applause and then answered several questions posed by his audience. Indeed, even after Jackie Eales had called for a final vote of thanks to Paul, there were people who wanted to ask him other questions and to make further comments.

Finally, I just want to finish this week by saying that Dr Diane Heath and I will be attending Dr Jayne Wackett’s Memorial Service at Wye parish church tomorrow afternoon. Some of you may remember Jayne from her role at the Historic Gardens study day that the Centre held a couple of years ago. Jayne led the Tudor Garden design workshop and I well remember the different designs produced by the various groups under her tutelage. That day saw her husband Dr Alec Forsyth (biology lecturer at CCCU) leading a workshop on grafting that was also very well received by participants. So tomorrow will be a very sad day and it only remains for me to say RIP Jayne, you were a lovely person and it was a privilege to have known and worked with you.

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 1831

1831