I thought I would just begin by mentioning that Dr Diane Heath is intending to submit her HLF ‘Medieval Animals’ project application in the next week or so, which is excellent news! Also good news is that several of the taught MEMS MA students are going to be working on Canterbury research projects this term: Amber’s project is linked to the Roman Museum, Ed will work on Canterbury Castle, Beth will be looking at the history of St Mildred’s church and its patron saint, keeping with Kentish saints Steph will be exploring material for the ‘Kentish Saints and Martyrs’ exhibition to be held at Eastbridge, while Alisha and Lizzie will be working with Professor Louise Wilkinson in conjunction with people from the Medieval Pageant organising committee.

For this week I want to focus on the ‘Digital Kent Map 2020 symposium and pilot: ‘Dickensland’ #KentMaps’ that took place yesterday (Wednesday). This was organised by Professor Carolyn Oulton who is the driving force behind the project. Some of you may remember I reported on the 2019 symposium: https://blogs.canterbury.ac.uk/kenthistory/victorian-kent-dickens-land/ and in Carolyn’s opening presentation she talked this time about the launch of the pilot map ‘Getting Lost in Dickens’ Land’. Unfortunately, I arrived late and missed Carolyn’s talk but from the booklet it looked as though she with others have had a great time creating several curated walks using characters from Dickens’ novels, such as those from David Copperfield and Great Expectations, which took the intrepid walkers through Canterbury, around Thanet, and through the Medway area into Rochester before ending at Gad’s Hill.

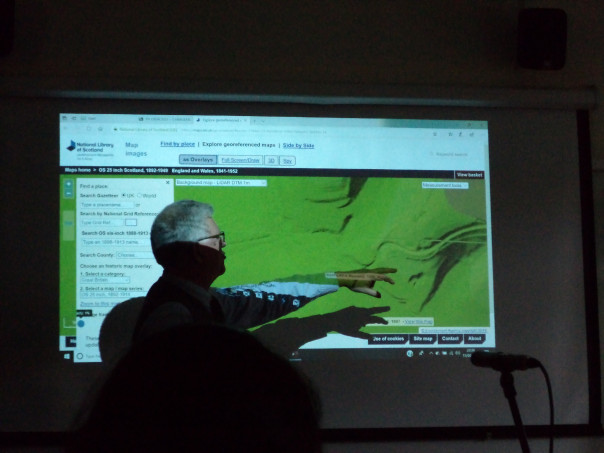

Professor Peter Vujakovic was the second speaker and I did hear at least part of his presentation that drew on the concept of ‘taskscape’ [see also Peter’s Nightingale Lecture: https://blogs.canterbury.ac.uk/kenthistory/ian-coulson-awards-and-nightingale-lecture/ to think about the way those in the past had scratched, scraped and scarified the landscape taking as his case study the Downs behind Wye. Among the marks Peter explored were prehistoric earthworks, the ‘Crown’ on the hillside, and chalk pits, as well as the ancient trackway that follows the edge of the hill, neither being in the soggy valley bottom nor on the windswept top of the Downs. As Peter said, this is often designated The Pilgrims Way but that would seem to be a ‘romantic’ 19th-century designation in that pilgrims came from all parts to Canterbury, and presumably only joined together as groups before entering especially dangerous terrain, such as the Blean Forest if coming from London, albeit those on a more southerly west-east route would have avoided the Weald. But to return to Peter’s talk, he showed the value of OS maps before turning to the way such new techniques as LiDAR are allowing us to peel back the landscape to reveal what lies beneath the tree cover. He was especially keen to highlight the use of chalk pits as indicators of human interaction with the landscape, and how these pits are predominantly found in association with drove ways and other ancient tracks, something Belloc considered in his The Old Road (1904) – a taskscape in action.

Moving on, the next speaker Elizabeth Waterman-Scrase was keen to demonstrate how she seeks to use sights, sounds and smells of the past to re-create as far as possible historically accurate landscapes that can be the basis for historical fiction. She drew on several historic maps and paintings, as well as a contemporary recipe for a perfume from flowers and herbs that she had followed to provide an ‘authentic’ scent. Such methods have provided her with some interesting results, but as one of the questioners said afterwards, there is the issue of authorial intent for painters, for, just like other producers/creators, they were responding to current ideas and agendas and we are not seeing a simple reproduction of ‘reality’ whatever that may be! A sentiment Elizabeth agreed with, for she has taken considerable reassurance regarding her approach from the comments of Hilary Mantel on the writing of historical fiction.

After a welcome tea break – thanks Carolyn, we heard from Dr Peter Merchant as he detailed Henry James’ deployment of stately houses, including Hever Castle, in his development of an idea that at various times was published as a novella and produced as a play. This organic creation and re-creation contained certain re-occurring themes, not least the role of the old English aristocracy, the value of new money from overseas and notions of national heritage, as well as how far they were compatible and the tensions they aroused at certain times and in relation to specific places.

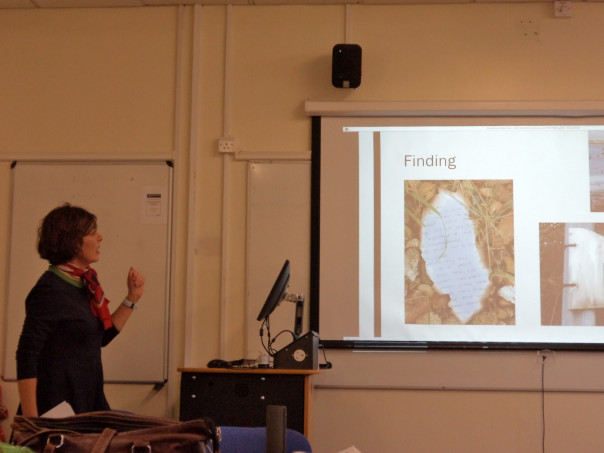

This brought us to Caroline Millar who is engaged in writing a collection of short stories inspired by the Thames Estuary, drawing on amongst other influences the similarities and differences between the south coast of Essex and Kent, specifically Whitstable. Her initial intention had been to use the coastal landscape as she walked the coastline as her inspiration, but this didn’t prove to be as fruitful as she had hoped, consequently she turned to what she found along the way – a discarded letter fragment, for example. Yet, even this was somehow not what she decided she was searching for and her interest in landscape and memory, coupled with her delving into film, TV and books, especially W.G. Sebald’s The Rings of Saturn, has led her to rethink the creative possibilities of not walking and instead constructing her own landscape.

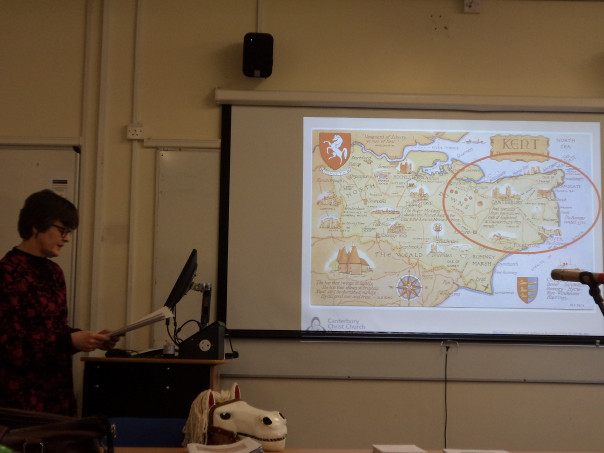

The final presentation I was able to stay for was Jacquie Stamp’s on that east Kent phenomenon the hooden horse, although today they have infiltrated the west of the county. Now I ‘met’ one a couple of years ago in The New Inn: https://blogs.canterbury.ac.uk/kenthistory/canterbury-christmastide/ so it was nice to meet another. Jacquie provided us with a summary of what is known about this presumably late 18th-/early 19th-century revival of an earlier tradition, although such customs have probably changed considerably over time albeit the earlier use of an animal skull, some sort of link to the apple harvest and the timing – performed at Christmastide may have a long history. More dubious are links to mythical early Anglo-Saxon leaders and the meeting between men from Kent and Duke William in 1066, such ideas perhaps a product of Victorian interests in the Gothic and a desire to highlight the seemingly different nature of medieval Kentish society. All of this was fascinating, and the horse was a major hit among the audience, indeed ‘he’ has been invited to come to CCCU next autumn to take part in the university’s hop harvest celebrations!

I think finally for those who are interested in Canterbury’s history, I’ll just mention that later that evening I attended the Canterbury Historical and Archaeological Society [CHAS] lecture, which was given by Dr Anne Le Baigue on Archbishop George Abbot’s conduit. This was constructed c.1620 close to St Andrew’s church in the centre of Canterbury, and was a gift to the city and corporation. However, relations between archbishop and city, while never good, had taken a turn for the worse at this time and Anne discussed how and why this relationship had soured, the state of religion at the cathedral and in the parishes, and how this affected and was affected by relations between first James I and his archbishop and then between his son and Abbot. If this sounds interesting, please refer to Anne and Avril Leach’s article in Archaeologia Cantiana vol. 139 (2018), published by Kent Archaeological Society. However, I should like to say he did establish a rather splendid hospital in Guildford, which does survive and is an exceedingly impressive building.

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 1221

1221