This week has been Graduation at CCCU and among those receiving their doctoral degrees were Dr Lily Hawker-Yates and Dr Dean Irwin, two stalwarts of the Kent History Postgraduates. Having been part of the team working on one of the HS2 digs, Lily has been very busy recently and is about to take up a post in Coventry as the outreach officer for another excavation. Dean is busy working and looking to publish articles as well as an edited collection soon, and both will be speaking at the Medieval Canterbury Weekend 2022. – more news on that next week.

This week there was also a meeting of the Kent History Postgraduates, and we took the opportunity to celebrate Dean’s and Lily’s achievement at the same time. Consequently, a good number of the group were on campus for Maureen’s presentation which was conducted through Teams for the benefit of those off campus. Moreover, following the seminar about ten of us went for lunch which was a highly enjoyable occasion and for some the first time that they had met others from the group in person.

For the rest of this blog, I’m going to offer a report on Maureen’s presentation. However, firstly I thought I would mention that Dr Claire Bartram has been developing the Aphra Behn project in terms of looking for funding streams, Dr Diane Heath’s is busy working with Tim Ireland and Rebecca Hobbs on a collaborative University of Kent School of Architecture design competition. The winning design will be used to create a Green Heritage art installation as part of the Medieval Animals Heritage project. In addition, I’ll be speaking at the Kent Archaeological Society’s Fieldwork conference on Saturday and the Ian Coulson Memorial Postgraduate Award Fund is looking to support two doctoral students. For further details, please see: https://www.canterbury.ac.uk/study-here/scholarships-and-bursaries or contact sheila.sweetinburgh@canterbury.ac.uk

So now to Maureen’s talk on the medieval iron works of the Weald, with special reference to those near Tonbridge. This is a new area of research for her having looked in detail already at the exploitation of the woodland in the Weald in terms of hunting, seasonal grazing and timber. Often cloth and iron production are seen as Tudor Wealden industries, but both have their roots in the Middle Ages and even though none of the medieval bloomeries of the Weald survive, the Wealden Iron Research Group has sought to track down the sites by looking for the tell-tale deposits of slag – the waste products of iron smelting. By the end of the 15th century, the bloomery was obsolete having been replaced by the more efficient and effective blast furnace, which would mean the far greater production of iron that was necessary for the manufacture of cannon.

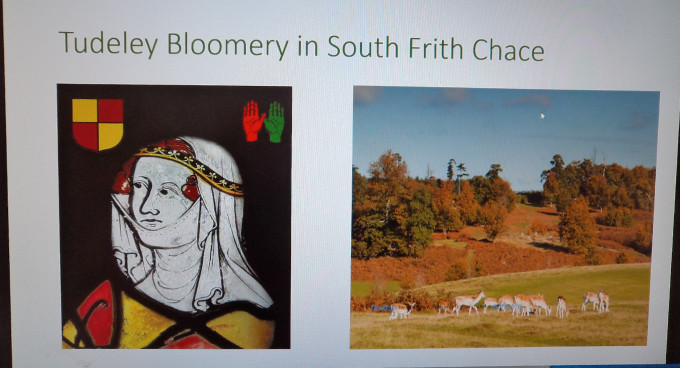

Having outlined the process of smelting iron using the bloomery method, including the importance of charcoal to ensure a high enough temperature could be reached, Maureen turned to the works at Tonbridge. For only in the case of Tudeley do we have accounts for medieval iron production in the Weald and this Maureen believes was within the area of South Frith. This was held by the de Clare family, which meant that by the early 14th century and the lack of male heirs was in the hands of the de Clare sisters, South Frith amongst the possessions of Elizabeth de Clare who married three times, becoming a widow for the third time and thereafter remaining single for the rest of her long life and dying in 1360.

As a powerful landholder in her own right, she was able to exploit the natural resources of South Frith through the sale of timber and seasonal grazing, but she apparently looked for other methods instituting iron working using local iron stone and charcoal produced there, the new bloomery expected to bring in a profit, as well as providing iron for use at Tonbridge Castle. As Maureen said, there are accounts for this bloomery at Tudeley for the periods 1329 to 1334 and then again 1350 to 1354, and she thinks there may have been a second such works at Bourne mill nearby.

During the initial phase, the Tudeley accounts show that four workmen were employed as blowers who were skilled workers who knew how to maintain the required high temperature in the bloomery. As such they were well paid at 5d and a farthing per bloom of iron produced, as well as receiving food and drink. In the first year, things seem to have gone well and even though medieval accounting takes no account of capital assets or their book depreciation, 194 blooms were made and a profit of £8 was recorded. Nevertheless, within a short time direct production ceased and the works were rented out instead. Moreover, this seemingly did not improve matters and it is feasible that the rebuilding if the works in 1341 was due to their previously falling out of use completely.

The Black Death seems to have had a further impact and the 1350/1 accounts point to more (remedial) building work and the shift to the employment of Thomas Springet as the ‘keeper of the workers’. This appointment suggests a greater professionalisation of iron working, acknowledging his expertise through his higher wages and the provision of a gown. Such confidence was initially justified in the form of 252 blooms produced in the first year, but this level was not maintained in subsequent years and again the works were rented out from 1354, including to the Culpepers. This family would in the 16th century become significant iron masters in the Weald, but not at Tudeley, the works yielding nothing in rent in 1374/5 in part because it was seemingly difficult to get skilled workmen and charcoal was having to be bought in.

Maureen’s presentation generated considerable discussion, not least what was happening to the iron and whether it was being used locally or taken to London, or both, Some was apparently used at the two forges at the castle, as mentioned in the 1385 account, but how many smiths and other metal workers there were in Tonbridge during the 14th century is exceeding difficult to ascertain. Discussion also brought in what happened subsequently in the 16th century, which will form the subject of a later presentation and at that point the group decided to thank Maureen for a fascinating talk and adjourned to the Veg Box for lunch.

And finally it gives me great pleasure to announce that the winner of the Lawrence Lyle Memorial History Prize this year for the best Taught MEMS and Modern History Masters dissertation for 2020/21 is Alex Forster, whose dissertation came out just above another distinction dissertation by Michael Byrne.

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 1098

1098