As we are almost into May and lockdown measures are still in place, I thought this week I would take the blog back into the Middle Ages, which I’m sure will surprise no one! Also, I expect a sizeable number of people will know that I have been researching hospitals in medieval England, especially in Kent, off and on for longer than I care to think about. Consequently, with the emphasis on the sterling work being undertaken by hospitals and care/residential homes under the NHS banner at the moment, I thought a short piece on: who cared for the sick in medieval England – the role of the hospital, might be appropriate and of interest.

I thought I would start with a quote from the Ancrene Riwle, in part because anchoresses have always been part of Louise Wilkinson’s modules on ‘medieval women’, but also because it nicely illustrates the medieval theological idea of the redemptive power of suffering for those who bore such tribulations with humility and fortitude: “God tests those he loves in the same way as the goldsmith refines gold in the furnace. The base metal vanishes completely, but the pure gold emerges truer and better than ever it was before… Sickness is your goldsmith, who, in the bliss of heaven adds gilding to your crown.” Out of interest, if anyone has ever read/seen the medieval ‘morality’ play Mankind, the same idea is used there – if you haven’t and you get the chance, do, it is brilliant fun. However, I guess I’m biased because I taught it for over a decade as part of an early drama module.

Both the Ancrene Rewle and Mankind highlight that the welfare of one’s soul was of central importance to the medieval Christian as s/he sought to negotiate the perils on earth to achieve the promises of heaven. Hence this dynamic relationship between body and soul meant that the well-being of each was completely interlinked, but the soul took precedence. For the founders, patrons and hospital benefactors of medieval Christendom, this relationship between care for the soul and care for the body was at the heart of their charitable giving.

Now the lives of medieval people in such things as Horrible Histories is that they were nasty, brutish and short. While this is obviously a caricature, dearth, famine, disease and injury were all significant factors, a situation worsened in some ways from the coming of the Black Death and subsequent plague outbreaks, albeit generally survivors were better fed in the late Middle Ages. However, the fear of sudden and unexpected death which would not give time or opportunity to die in a state of grace led, in part, to the production of manuals concerning the art of dying well, the person enduring, even welcoming pain as a way of achieving spiritual redemption. Thus the death bed was largely the province of the priest rather than the physician, the last will and testament offering a final chance to engage in pious and charitable actions.

As I expect many of you know, contemporary ideas about sickness stemmed from a combination of ideas from the ancient Greeks and the early Church Fathers – disease as an imbalance of the four humours and St Augustine of Hippo’s contention that none could escape suffering and death, the legacy of Original Sin, to which was added an individual’s extra load that was due to his/her inability to lead an exemplary Christian life. Consequently the sufferer should accept pain with humility, thereby avoiding the far worse ordeal in purgatory. Now we shall never know how widely accepted such ideas were and sleeping draughts of varying degrees of effectiveness were available for those who could pay, but you do get examples such as Lady Margaret Beaufort, Henry VII’s mother, who suffered terribly from arthritis but still spent hours on her knees praying as part of her pious way of life.

Furthermore, Christ’s healing miracles did mean that the Church could reconcile its teaching about sin, disease and suffering with the use of earthly medicine, although it must be allowed that often the sufferer was probably better off without such interventions by physicians or barber-surgeons. Nevertheless, taking the idea of Christ the physician of diseased souls, the Eucharist was thought of as having miraculous powers, even against earthly disease, and at Dijon, for example, the Host became the centre of a healing cult. Saints, too, could offer such miracles, and pilgrimage remained important throughout the Middle Ages. Adding to this, charitable acts, based on the Seven Corporal Works of Mercy, of giving to the poor would not only aid the recipient, but would please God and should make him more compassionate towards the giver. One form of such alms giving was to support a hospital.

Hospitals in medieval England came in a wide range of sizes, from the tiny hospital at Whitby where a leper lived by the bridge to the great hospital of St Leonard in York which, in the 14th century, housed 18 clerics, 30 choristers, 16 sisters and female servants, 10 corrodians, and between 144 and 240 poor-sick people. Furthermore, some hospitals only lasted for the life-time of a single person, whereas probably the first, at least from post the Norman Conquest, are still going strong, being Archbishop Lanfranc’s twin institutions of St Nicholas’ hospital for lepers at Harbledown and St John’s for the poor and infirm, which is just outside the line of Canterbury’s city wall. This means we shall probably never know just how many hospitals there were in medieval England, although I would suggest that there were over 30 in Kent alone.

Now Professor Carole Rawcliffe has used two categories: those for lepers and those for non-lepers, but I prefer Professor Nicholas Orme’s idea of distinguishing between earlier hospitals and later almshouses, with the addition of differentiating between Dr Patricia Cullum’s small transient houses, which she calls late medieval ‘Maisons Dieu’, and those far better endowed where the almsfolk were the founder’s bedesfolk. I also think it is worth separating those for the poor and infirm, and those for pilgrims (and other travellers). There are examples of these different categories in Kent, but for the purposes of the blog, I’m just going to explore briefly the relatively small number nationally that took in the sick-poor. For most sick-poor people care came from family, friends and neighbours, not hospitals. By and large hospitals for the poor and infirm in England offered places for longer-term brothers and sisters, and if the sick-poor were admitted they either recovered and left, or died, in which case they would receive Christian burial. St John’s hospital at Sandwich kept an old sheet specifically for that purpose. Possibly in part as a consequence of this different type of institution, England had nothing comparable to the extensive and more organised provision for the sick-poor in the Italian city states and other parts of continental Europe. Ok, we have already seen St Leonard’s at York, but elsewhere it was not until the Tudors that more beds of this kind really became available: 180 beds at St Mary without Bishopsgate and at another London hospital, Henry VII’s foundation at the Savoy which was intended to take in 100 poor men each night, preferably the sick, but not the leprous. In Kent (if we discount the hospitals that took in poor (and sick) pilgrims), probably the greatest provision for the sick-poor was at St John’s, Sandwich, where the three chambers at the back of the hospital could accommodated at least eleven people. Although not all would have had a bed, there was a small bed next to the privy.

So what sort of people went into these hospitals? Some hospitals explicitly excluded groups such as cripples, the blind, the feeble, lunatics, pregnant women and other ‘intolerable persons. Alternatively a few showed some degree of specialism, including St John the Baptist’s hospital at Oxford that received casualty cases, St Mary Magdalen’s hospital, Newcastle, that cared for victims of pestilence once the lepers had gone, while several London hospitals and a few in Kent specifically took in women in childbirth. For Kent, among these was Canterbury’s third archiepiscopal hospital – St Thomas’ that catered for poor (and sick pilgrims). London, too, offered provision for the insane, at a hospital near Charing Cross, as well as St Mary Bethlehem (Bedlam).

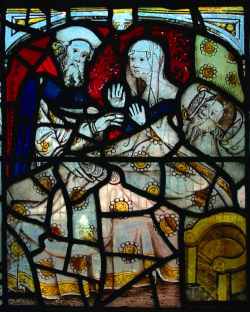

Entry was frequently conditional on saying confession, and what might be termed this spiritual washing was at the Maison Dieu in Thetford accompanied by physical washing. In some of these hospitals at least, the beds for the sick-poor were aligned on either side of an infirmary hall, or ‘nave’, so that they might look into the chapel at the east end of the hall, whereby they would daily witness the elevation of the Host and hear the divine office. For example, such arrangements were at hospitals dedicated to St Mary at Chichester and Newark. However, Kentish examples are rare, the hospital for poor pilgrims at the Maison Dieu, Dover, having such a system. This lack of infirmary hall style hospitals in the county may in part be due to the absence of houses primarily or exclusively catering for the sick-poor, most hospitals accommodating lepers or the poor and infirm as the house’s brothers and sisters.

While the primary care for the soul was the jurisdiction of the hospital’s priest brother(s), the sufferer’s bodily needs were in the hands of the hospital sisters, as well as female servants at the larger houses. Probably many of the sisters were skilled in the use of herbs, but the provision of better food and lodging, and general nursing care may have been more significant, although at possibly 3 to a bed contagion would have been an issue. Even though a few hospital accounts mention payment for medical services and purchases from apothecaries, these are more likely to have been for the brothers and sisters, not the sick-poor. Similarly, physicians occasionally held the mastership of a hospital, but most were sinecure appointments, and even where the master was resident, he would have gone outside the house to find his patients. Yet, and again perhaps to a degree in the light of what was happening in Italy and elsewhere (Spain, France, the Low Countries, and central Europe), by the early 16th century things were starting to change, but most of the few examples of barber-surgeons or physicians working in hospitals relate to London.

Consequently, just as today in terms of the COVID-19 virus, nursing skills remain paramount, whether we are talking about highly technical aspects or human empathy. Even though there have been considerable differences in what the term ‘hospital’ meant since the Middle Ages, as well as major culture changes, including differing belief systems, looking back into the past offers some interesting comparisons. For medieval society was indeed different compared to today; yet care for the sick continues to be paramount, whether we are talking about provision in hospitals or in the community. Consequently, I wish everyone reading this and all of your families all the very best during these difficult times.

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 2375

2375

Hi Sheila

Very much enjoyed your article. Care for the sick poor sounds very basic. Who were treated at the monastic infirmaries such as St Augustines? They had a large complex there and a fine library of medical and herbal texts so must have been able to give a much better standard of care and maybe even surgery.

Hi David

Thanks for this and yes they did at St Augustine’s and at other great Benedictine houses. Although there isn’t a great deal of evidence, what there is points to monastic houses caring for their own brethren in terms of the infirmary. Barbara Harvey’s, Living and Dying in England, 1100-1154 is useful here.

Best wishes, Sheila