Thanks firstly to Dr Diane Heath for last week’s blog, and today I thought I would start with Professor Louise Wilkinson’s virtual ‘Farewell’ last Friday where she was joined by most members from History, several members of the School of Humanities administration team and Dr Harriet Kersey from CCCU Research, who is a former doctoral student of Louise’s. As all agreed, it is a great pity that such a great scholar and lovely, caring person is leaving CCCU after about sixteen years, but as her parents will still be here in Canterbury for the time being, we haven’t ‘lost’ her completely. Consequently, there will be a ‘proper Farewell’ once the lockdown is over when she will be given a rather special gift to mark everyone’s appreciation of what she has done for History and the university more widely.

Yesterday marked the third Kent History Postgraduate virtual meeting. This time everyone made it except for Peter, whose work with the CCCU chaplaincy team means he cannot always manage it. Consequently, after our usual catch-up on various matters people have been doing beyond their research, we went round the group to find out how people are coping and what they have been doing on their own doctoral projects. Again, this is in no particular order and I’ll start with Janet’s work on Ruxley Hundred. Concentrating on the period of the high middle ages, Janet is continuing to work on her introduction. Finding contextual material on London is fine but locating similar material for north-west Kent is proving to be much more challenging. Dean wondered if a collection called Compassionate Capitalism that uses the Hundred Rolls might be useful, and Janet is going to follow this up. Dean, himself, has just had his final review meeting with his two supervisors and is now pulling together the final parts of his thesis and will then start on checking and editing. Maureen also thought Dean’s suggestion might be useful for her research on the town of Tonbridge. She has finished working on the 1385 account and, as well as starting to think how she will write up comparatively the three accounts, she is looking to download the later PCC Tonbridge wills from TNA. Jane is also working on wills. Currently she will have to confine her research to the PCC wills because, like Maureen, there is no access to the Kent History Library Centre for the Rochester diocesan records. She mentioned that the cancellation of the IHR database course was a great pity and she is continuing to record on an Excel spreadsheet. This sparked a discussion on databases, social network theory and GIS mapping and most people thought they would benefit from training on these. Lily mentioned that she had done a GIS course last year and found it both interesting and helpful, and not as difficult had she had expected it would be. She is making good progress on the examiners’ comments and has been doing the part on place-names, while Tracey reported that she had been redrafting her introduction. In addition, she said she had heard from someone who thought that their research might dovetail concerning certain landholdings in the Nonington area. Thus you might say that yesterday there were several instances of social network theory in action!

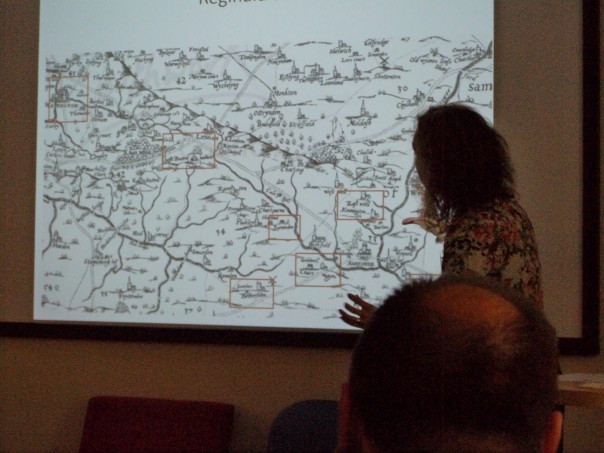

I appreciate that some of you will know Dr Claire Bartram already, but as she is coming in to replace Louise as a co-director of the Centre, I thought I would offer a brief summary. Claire is a Senior Lecturer in English Literature within the School of Humanities having joined the Christ Church in 2005. Going on from her doctoral thesis on ‘Gentry Writers in Elizabethan Ken’t, she works on book culture in provincial society, especially Kent. Her recent collection of essays with Peter Lang Publishers, Kentish Book Culture: Writers, Archives, Libraries and Sociability 1400-1660,foregrounds the activities of provincial readers and writers, juxtaposing the book culture and writing practices of different social groups. This approach is inspired by D. F. McKenzie’s emphasis on the need to consider ‘the human motives and interactions which texts involve at every stage of their production, transmission and consumption’ and by the work of Margaret Ezell who highlighted the need to recover ‘perished authors’ and to explicitly consider ‘the lived material conditions of reading and writing in the provinces’. Thus, as you can see her interdisciplinary approach fits extremely well within the ethos of the Centre.

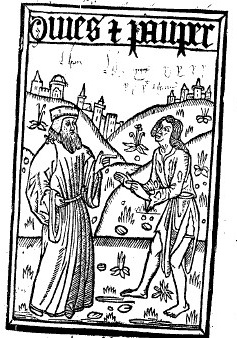

Consequently, having talked about John Serle, a Sandwich town clerk a couple of weeks ago, I thought this week I would introduce you, albeit briefly, to a network of book users who lived in and around the cathedral precincts at Canterbury in the late Middle Ages. I am going to do this by thinking about friendship, and in relation to monastic friendship, this topic that has come more to the fore since the work of Julian Haseldine. Taking as a starting point his idea that ‘heightened expressions of [such] friendship of a more private, intimate kind,’ might have been envisaged alongside ‘the traditional concept and use of friendship as an integral part of social and political relations’, several years ago I looked at the clerics attached to the various chantries and monastic almonry at Canterbury. I wanted to see if these ideas might have extended beyond the cloister to those in secular colleges or even among groups of chantry chaplains. For they might have been seen or seen themselves as engaging in some form of communal existence, their lives governed by the spiritual duties they were expected to perform for their respective founders and patrons. Furthermore, they indeed co-existed physically with the monastic brethren of Christ Church Priory, and on a daily basis they must have been fully aware of the monks as each group performed the necessary liturgical offices.

As we have seen already, historians have looked outside their own discipline for theoretical models in an attempt to investigate such issues, and these interdisciplinary endeavours have often proved to be exceedingly fruitful. For example, the mapping of networks has become a useful tool, the webs of connections and inter-relationships highlighting the complexities of friendship. Nonetheless, there remains the problem of introducing some form of time depth into any such analysis, for these webs were not static over time, either in terms of those involved or the privileging of certain relationships.

For my purposes here, I’m undertaking a less ambitious goal, although not without its difficulties, for the testamentary sources of the Canterbury chaplains might be said to offer only a snapshot of the individual’s relations with some for whom they ‘had regard’. Yet even though they cannot be viewed as comprehensive, wills were often drawn up when the testator was close to death and this highly significant point in the life cycle may have intensified the ties of affective friendship personally and communally within the framework of the desire to ascend to God.

By the late fifteenth century, an impressive array of chantries had been established within Canterbury Cathedral, and this was in addition to the six priests who officiated in St Thomas’ chapel at the almonry. None of the cathedral chantries were on this scale, but at least two had been founded for more than one chantry chaplain: that of the Black Prince’s chantry in the undercroft, and Archbishop Thomas Arundel’s chantry in the nave. This growing community of secular chaplains also included the master of the Lady Chapel choir, the choir boys drawn from the ablest singers at the almonry school. Yet, even though all the seculars did not share the same living space, for example the two Arundel chantry chaplains were given a house on the south side of the cathedral, and next door was the house of the Brenchley chantry chaplain, unlike their monastic brothers, the chantry chaplains in the almonry do appear to have lived communally on the far side of the precincts. And it is against this background that the wills can be considered regarding matters of friendship.

Now I’m going to keep this brief, but I’ll mention a few books as well as other bequests just to offer a flavour of these ideas. Taking first gifts that testators might have intended would help sustain the secular Canterbury community, John Hawkyn and John Clerke made bequests to specific individuals. Hawkyn’s, one of the Arundel chantry chaplains in 1511, wanted Sir Philip, his fellow priest, to have 6s 8d to pray for his soul and so that he would ‘be good’ to Hawkyn’s poor kinsman, another priest called Sir William Gilbert, who in turn was to receive all of Hawkyn’s books in which he had written Gilbert’s name. John Clerke also sought to aid certain of his fellows at the almonry that would in turn aid them collectively by giving amongst other bequests some of his liturgical books to John Gower and Laurence Gyle, the latter in addition receiving Clerke’s copy of the ‘Golden Legend’. Moreover as well as personally directed giving, Clerke can be seen as seeking to distribute tokens of friendship towards his community through his collective bequests – he intended that his antiphonal should be used in the almonry chapel by the serving priest after his decease. One of the Black Prince’s chantry priests, Peter Maxy apparently expressed similar feelings, leaving his book of ‘Decretels’ to those who would be serving at the chantry after him.

The personal bequests to members of the cathedral priory are more difficult to see in communal terms, especially the gifts of money such as the 26s 8d given by John Clerke to Dominus Thomas Herne and the 38s 4d bequeathed to Dominus John Wodnysbergh, the prior. Yet, these sums are interesting because they comprised amounts owed to Clerke by diocesan and parish clergy, perhaps indicating a web of contacts among religious men based on a complex mix of exchange and reciprocity. Additionally, James Cursume’s numerous book bequests, including several to monks at Christ Church, had the potential to be communal but equally may have been retained by the recipient. Amongst these were Cursume’s epistles of St Paul to Master Sellyng and his gloss on St Paul to Master Bockyng.

Relationships between those inside and outside the cathedral precincts were not confined to special events such as funerals but is seemingly evident in the personal and collective bequests made by the Canterbury chaplains. John Hawkyns wished that his old college, perhaps at Oxford, should receive the pick of his book collection, thereby remembering his gift in friendship. The idea of linking bequests to education as a means of enhancing the individual and the communal, and thus the ties of friendship, may also have influenced James Cursume’s decision to aid poor scholars studying at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge through an annuity of 40s, which was to be administered by Master Seynthwary.

Yet it is striking that none of these bequests employed what might be called the language of friendship, and of the wills cited here only Roger Downvyle used any vocabulary of this nature, and then only in reference to a specific relationship. It seems Downvyle had recently been seriously ill and those who had apparently helped him the most were the parish clerk at St Alphage’s and his wife. Their care had extended to buying things for his benefit and Downvyle wanted to thank them for their generosity. His bequest to the couple highlights the personal, practical, aspirational and commemorative facets that could be engendered through gift-giving. Their son was to receive some of Downvyle’s clothing, the choice of what was best left to his executors’ discretion, and a lined coat was to be made for him at the chaplain’s expense. Furthermore, this well-attired boy was to receive the chance to better himself through the provision of a year’s schooling, perhaps at the city’s grammar school in his home parish or at the nearby almonry school.

From these few testamentary examples, many of which involved books or education, I hope you can see ideas about friendship – what it may have meant and how it may have been expressed, including different relationships that might have been sustained beyond the grave, as a consequence of bequests made both individually or collectively. And this type of analysis is very much in keeping with Claire’s research interests, although the relationships she works on were in place a century later.

Finally, Dr Gillian Draper (Visiting Research Fellow) was last week giving two virtual presentations on using churchwardens’ accounts and workhouse records to ‘Family Tree Live’, these are now available (free) on the BALH website https://www.balh.org.uk/education-conference-presentation-material and I expect some of you may remember the Centre had a 1-day conference on churchwardens’ accounts: https://blogs.canterbury.ac.uk/kenthistory/kent-history-postgraduates-and-sources-and-themes-in-parish-histories/ that featured the database of such records maintained through the University of Warwick.

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 849

849