This week is more of a brief note in that Professor Louise Wilkinson has been very busy writing the report on History’s impact work over the last few years, including the activities of the Centre, as well as getting matters organised for the new undergraduates, while Dr Diane Heath has also been busy working on her ‘Medieval Animals’ application. She has also been getting ready for the Canterbury Education Day where the Centre is one of the places involved. The initiative is organised by The Canterbury Tales, and St Augustine’s Abbey is another of the venues where activities take place.

In contrast to these Canterbury-based activities, I have been away from Kent having been at ‘The Fifteenth Century’ conference in Exeter. Among the plenary speakers was Professor Caroline Barron, whom some of you may remember will be coming to Canterbury in April 2020 to speak at the Medieval Canterbury Weekend. Next April she will be talking about Thomas Becket as a Londoner and his legacy within his native city, for the influence of St Thomas permeated city life in medieval London until Henry VIII ordered the destruction of his shrine and the removal of his name from all liturgical books. However, for the Exeter conference, Professor Barron chose to investigate the chronicle accounts of The English Rising (Peasants’ Revolt) of 1381. She was especially keen to compare Jean Froissart’s Chronicle, which is often quoted by historians but not seen as accurate regarding the Rising, to that of the Anonimalle Chronicle, whose author is thought to have been an eyewitness of events in June 1381, regarding their descriptions of who was in the Tower of London on the night of Wednesday 12 June and who was also with the young Richard II at Mile End on the following Friday. For as she said, there is considerable correlation between the two accounts and where they differ is very informative and may include the names of those Froissart consulted for his work.

West front of Exeter Cathedral

After outlining the ways Froissart’s Chronicle has come down to us, she gave a short account of his career. In particular, she noted how he moved in aristocratic circles in Flanders and France and how he seems to have sort out information on events, especially from the various heralds, as a means to gain eyewitness accounts, albeit he is envisaged as viewing matters through a chivalric lens. Her candidates for his informants about the situation in the Tower that night are two among the four Flemish nobles that Froissart mentions as being there.

As well as proposing that Froissart’s Chronicle should be seen as more reliable than it has been given credit for in the past, Professor Barron was keen to highlight the importance for Foissart of the urban dimension, especially the role of the Londoners, but equally that he appears to have had a deep concern about the problems of serfdom in England. Thus, in terms of the theme of the conference – the British Isles and their mainland European neighbours – Froissart may be offering a more European perspective on events in 1381, as mediated in the first place through the eyes of these Flemish noblemen.

Bishop Oldham founder of Manchester Grammar School, funeral monument in Exeter Cathedral

The two other plenary lectures by Dr John Goodall (English Heritage) on Europe and the Perpendicular Style and Dr Malcolm Vale (St John’s College, Oxford) on ‘political nostalgia’ in terms of England and its continental neighbours between 1450 and 1520 were similarly fascinating. Nevertheless, I’m going to leave them aside and instead just give you a taster of one of the other sessions entitled ‘Alien Communities in England’. This was chaired by Susan Maddock (UEA) who had previously given us a great paper on the two-way relationship respecting merchants from Lynn in Danzig and vice versa. Among these exchanges, in addition to goods passing backwards and forwards between the Baltic and the North Sea, were the merchants themselves, certain apprentices and various types of craftsmen. Interestingly, there seemed to be more official structures to support the aliens in place at Danzig compared to Lynn, including a court held fortnightly. Nonetheless, those from Danzig apparently generally faced little if any hostility in Lynn, apart from the actions of a very few individuals, but in this case the town authorities were keen to stop such matters in favour of the foreigners.

This idea of how far and in what ways these aliens had a sense of belonging was important for all three papers in the session Susan chaired. Indeed, it might be said to be central to Joshua Ravenhill’s presentation. Joshua is a doctoral student at the University of York who is working on aliens in 15th-century London, and in the first part of his paper he explored why he thinks words such as integration and assimilation aren’t helpful when we are thinking about immigrant experiences. For not only was/is the situation not a binary between ‘foreigners’ and ‘natives’ but in many ways such concepts fail to take account of the ways immigrants become/wish to remain part of some ‘communities’ and not others. Such ideas may be seen in the works of social anthropologists such as Anthony Cohen and they offer a useful perspective, and one that Joshua sought to illustrate using wills made by aliens in London.

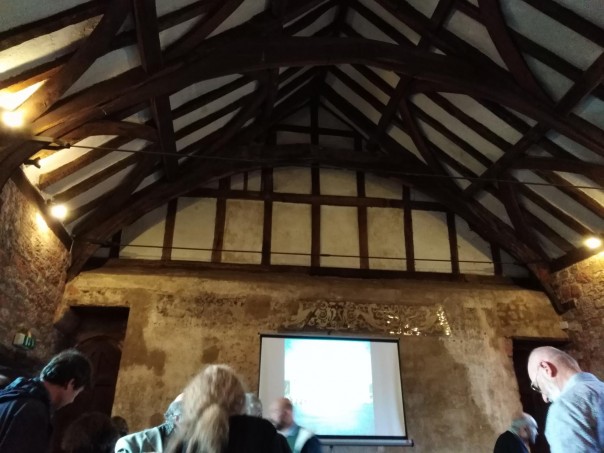

Great hall – St Nicholas’ Priory, Exeter

Paul Williams, another doctoral student and this time from the University of Exeter, gave us ideas about the alien community in Exeter in the late 15th and early 16th centuries. Using various national subsidies and Exeter corporation shop fines for his analysis, among the criteria Paul investigated were the types of occupation these people engaged in, whereabouts in Exeter they seemed to congregate, whether they only took service in their countrymen’s households and were they able to become freeman and hold civic and/or parish office. In many ways the picture Paul provided was one where it would seem such markers of belonging were taken up by at least a proportion of these aliens, and issues such as office holding would have been out of reach of many Exeter men anyway. Paul felt that this generally positive scenario was predicated on Exeter’s buoyant economy during this period, and that this was certainly a significant factor.

To take us to another provincial city, I took the audience to 15th-century Canterbury. Like Paul I deployed national and local records to explore even if only tentatively the lives of those below many of Joshua’s and some of Paul’s respective (merchant) aliens. To keep this brief, I just want to give a resume of a single individual to highlight the value of bring together these records, as well as the problems of identification.

Powderham Castle – built by Sir Philip Courtenay (d. 1406)

The man in question is Gylkyn Goodknight who, even if he wasn’t operating as an independent craftsman making caps until 1472, still may have been in Canterbury during the previous decade. The most tentative identification is from the 1463 alien list because in that year the royal clerk recorded the presence of Gilderkyn Ducheman, who was ‘Dutch’, suggesting he was from somewhere in the Low Countries. Two years later the clerk noted a Gilderkyn Goodknyght among the Canterbury aliens and he was again listed in 1466, although interestingly not in 1467 or 68. Provided this in the same man who then became an intrant (independent, licenced producer/trader), he worked as a capper for six years, residing in Newingate ward. His business appears to have been on a relatively small scale in that the Canterbury chamberlains never expected more than 10d annually, the fee having started at 6d. Whether he had married in Canterbury or the couple had come to the city together is unknown but in 1478 it was Katherine his widow who paid the licence fee of 6d, although she was unable to continue making caps after that, unless, of course, she remarried, but either way she disappears from the civic records.

Yet even these examples can only offer a partial sense of their time in Canterbury, by looking at a range of these immigrant ‘biographies’ and bringing them together, I think this approach provides a means to explore notions of longevity, a sense of belonging, social mobility, the presence/absence of ethnic/craft enclaves, as well as any evidence of hostility or opposition and their sense of place within the complex networks of ties to be found in late medieval Canterbury society.

As I hope you can tell, it was a very enjoyable and thought-provoking conference, so many thanks to the organisers and everyone who took part, and it probably resonated even more due to events that were unfolding concurrently at Westminster and beyond.

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 1829

1829