Many thanks to Dr Diane Heath for her blog last week about Professor Sandy Heslop’s lecture on St Anselm’s crypt in Canterbury Cathedral and the torchlight exploration of the crypt after his lecture. As a follow-up event, the Centre held an ‘Envisioning Workshop’ the next day with the intention of thinking how the ‘crypt creatures’ might be used to engage with a wide range of audiences.

For this week’s blog, I thought I would mention that Matthew Crockatt, the brilliant web and IT specialist who works on the Centre’s website among his many activities, has almost finished creating the necessary webpages for the Medieval Canterbury Weekend in 2018. This will be on 6-8 April next year and it will be our biggest History Weekend yet with a great selection of 25 ‘events’. As before tickets will be available using a pick-and-mix format and among the lecturers we are welcoming back are Helen Castor, Richard Gameson, Janina Ramirez and David Starkey. There will also be new faces and among the newcomers will be Caroline Barron, Marc Morris, Carenza Lewis and Stephen Church. So due to the splendid work of Matthew, Ruth Duckworth (Box Office) and their colleagues the Centre is on course to launch the Medieval Weekend webpages on 2 October and I’ll give you details of the short url next week.

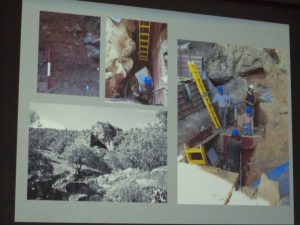

From under the Treasury, Canterbury Cathedral.

However, for this week what I want to mention is a lecture I went to yesterday, as well as bringing to your attention a fascinating short piece by a new Creative Writing MA student at Canterbury Christ Church. Harry Heath, who is especially interested in sci-fi and horror genres, came to Sandy’s lecture, the crypt tours and workshop and this is his take on these events:

‘Horror is, at its heart, the juxtaposition and intermingling of the fantastic and the mundane, a tradition that stretches back throughout the history of human creativity. Every demon, every chimera, every monster is rooted in human psyche and human perception. This is definitely true of the “crypt hybrids” (which itself sounds like the title of some long-forgotten horror fanzine) designed by St Anselm for Canterbury Cathedral’s vaulted crypt. They are intermixed and intermingled creatures – the heads of lions, the horns of goats, the wings of eagles and bats, &c – that were taken from both real life and bestiaries to inspire the thoughts of the faithful as they moved through the crypt, the carvings getting more and more complex as the pilgrim gets closer to the altar, to God. But the carvings are imperfect – the faces of the lions can look more like those of sheep, or goats, or (in one instance, at least to me) a curly-haired geography teacher with an enormous moustache. This was, at least in part, the point of the carvings; to demonstrate the limits of human imagination and creativity, the outer reaches of the ability to express what we have imagined, what we have seen; a strange and impossible thing, dredged out of a block of stone as metaphor and warning. The monks of the crypt also used the hybrids as impetus for study and self-reflection, a didactic dialogue with one silent, stone partner; the different parts of the animals combined with an expansion of the literal senses into the allegorical and the anagogical coalescing to bring enlightenment and revelation. Such revelation is the basis of horror writing at its best; this mix of influences spiralling through a point in space that, should the reader engage with it with expanded senses, will bring them closer to understanding about what it is to be human.’

If anyone would like to respond to Harry’s ideas, as with anything else in the blogs, please post your comments.

Animals at Shanidar.

Turning to the joint lecture organised by the Centre and the Friends of Canterbury Archaeological Trust [FCAT], it was great that the first of the autumn talks was given by Paul Bennett. For regular readers of the blog Paul needs no introduction but if you are new Paul is the Director of Canterbury Archaeological Trust and a Visiting Professor in the Centre. This summer he was awarded an MBE for his services to archaeology and in some ways his topic yesterday was highly appropriate because he was talking about the Shanidar cave, an internationally important site – indeed, ‘one of the top ten prehistoric caves in the world’ where he and a small team from CAT were working earlier in the year as part of a team from some of the best universities in Britain.

Paul began by describing the location of the cave which is in Northern Iraq (Iraqi Kurdistan) and high up in the Bradost Mountain overlooking the valley of the Great Zab River. As he said this is one of the most beautiful places he has seen and in addition to the stunning scenery the wildlife is fantastic – he showed slides of birds of prey, snakes, lizards, wolves and a particularly large and very hairy spider that joined Paul when he was excavating one of the Neanderthal graves in the cave.

For it is the presence of these far earlier people that has drawn eminent archaeologists to this site. Beginning in 1950, Ralph Solecki was the first to really work in the cave and during his early seasons there he was largely working on his own with a team of locals. Their methods were somewhat brutal involving the use of sledge hammers and even explosives in an attempt to tackle the large boulders, but by the third season and the arrival of Rose Solecki, his wife and a trained archaeologist, the excavation was more ordered and the importance of the deep stratigraphy was acknowledged. The sheer enthusiasm, energy and dedication of this husband and wife team meant that in four seasons they had discovered and recorded nine Neanderthals. They dated the majority of these individuals to the period 30-60,000 years ago, but new scientific work suggests this needs to be pushed back further, perhaps to more than 100,000 years ago for the earliest burial.

Paul discusses the Shanidar Neanderthals.

However, as Paul discussed, the importance of the cave may not only rest with the earliest burials because it is also the more recent that may open up exciting new ideas about prehistoric man during the two phases of the Neolithic period, which Ralph and Rose began to discuss in 2004 (The Proto-Neolithic Cemetery in Shanidar Cave). Moreover, as well as the Neanderthal bones, the cave yielded vast numbers of stone tools in addition to animal bones, all of which offered ideas about the lives of these individuals. Nevertheless, it is the Neanderthals that were the focus of greatest study and Shanidar I, an adult male of about 40/45 years, had been blind in one eye, had had a withered arm and a deformed lower right leg. Of course, all of this is interesting in itself, but even more importantly it indicates that we are looking at a caring community because such an individual could not have survived on his own.

The other burials also offered interesting insights, such as Shanidar II that had been placed in a shallow grave with worked tools, and Shanidar III, another adult male, who had died of an infection as the consequence of a stab wound. A burial that became the subject of particular study, and to a degree speculation, was that of a male in a foetal position. The soil samples taken from around the body indicated the presence of pollen from several plants including St Barnaby’s thistle, ragwort, cornflower, hollyhock and yarrow, which Ralph Solecki and others thought might indicate this was the burial of a ‘medicine man’. However, this burial has now been found to contain the bones of three individuals, plus such plants still grow in this area and alternative theories are that the pollen’s presence was due to contamination from the boots or clothing of the workers helping Ralph, or the culprit might be the Persian jird, a small rodent that lives inside and outside the cave.

Re-excavating the cave – note the presence of Paul.

As I hope you can see, this is possibly a unique site and its importance to our understanding of the development of mankind cannot be overstated, especially now that far more is known about the global movements of these different populations of prehistoric men, in addition to Homo Sapiens. For since about 2004 with great advances in DNA and other scientific testing it is becoming clear that we are looking at an increasingly complex picture. Thus, in 2015, the time seemed ripe to revisit the cave, its excavations and just as importantly the research archive held at the Smithsonian, Columbia University and by Ralph and Rose at their home, the latter including their day books and context record cards and plans.

Now there isn’t space here to give anything but a taste of the new findings that are starting to come out of this recent work, yet it is worth saying that the team led by Graham Barker and Christopher Hunt have found further Neanderthal bones, which indicate that some of the burials were of multiple individuals (see above). For this time, the excavations have been meticulous and have been conducted to the highest standards now expected at such a site, and among the specialists involved is Emma Pomeroy, who first studied under the late Trevor Anderson (CAT’s bone specialist), and is now an expert in her own right. In addition to matters of dating these burials, it is the question of the idea of burial itself that is interesting, because if it is the case it suggests a community that thought about the dead, may have had funeral rites etc. Furthermore, at the upper layers of the cave there is evidence of burning – hearths? And it is also clear that the stone tool ‘kit’ of these Neanderthals was different to that of early modern man.

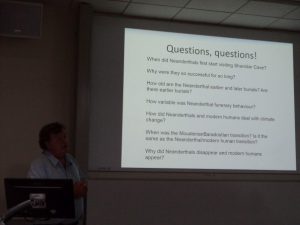

Questions for the team.

Finally, as Paul was keen to stress, the Kurds value Shanidar and its cave enormously, and this is clear at an organisational level as well as by individual Kurds, who will trek up the steep slope to the cave in their best clothes, almost on a kind of pilgrimage. The Kurdish KUKFA has being making the site accessible through the installing of security fences and story boards in Kurdish and English to tell the history of the place. The Kurds’ devotion and concern is another reason why Paul is keen to help ensure more archaeological work takes place at Shanidar. As always Paul’s enthusiasm was infectious, and following his lecture and the Q&A session afterwards, he left his audience spellbound as they trooped out of the lecture theatre after a most fascinating hour and a half.

As a postscript, I thought I would mention the Sixth Nightingale Lecture that will be taking place next Wednesday. Again, this is a joint event between the Centre and the Agricultural Museum, Brook, when Tony Redsell, an expert on hops, will explore ‘Hop Growing in Britain: Past, Present and Future’. All welcome and it starts at 7pm in Old Sessions House, Canterbury Christ Church, with a wine reception and exhibition on hop growing from 6.30pm in the foyer.

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 2310

2310