This year marks a rather special anniversary in Canterbury’s history because it is fifty years since the publication of William Urry’s Canterbury under the Angevin Kings.

To celebrate this ground-breaking study, Canterbury Cathedral Archives and Library, headed by Cressida Williams, was the host of a rather special event this afternoon. Several generations of the Urry family joined academics from Canterbury Christ Church University, Paul Bennett from Canterbury Archaeological Trust, people who had met and admired William Urry and those who had only known him by reputation or had read his books. This large crowd headed into the reading room at the archives to hear a series of short presentations, chaired by Cressida Williams. Of course, such a setting was highly appropriate because William Urry had been for many years the archivist at the cathedral, and it was he who had overseen the cathedral archives and library rise phoenix-like from the destruction of the Second World War.

To set the ball rolling, Bill Urry, William’s son, provided a fascinating summary of his father’s life. Beginning with his birth in 1913 in Northgate and his baptism in the church of St George’s, something that may later have drawn him to Canterbury’s celebrated Elizabethan playwright Christopher Marlowe and the subject of William’s second major study, Bill took us through to his father’s final illness and death in 1981. During his very full life, William Urry gained his love of history as a schoolboy at Kent College, riding out on his bike into the Kent countryside to explore the county’s medieval churches. Later, while working at London University Library, he studied at Birkbeck during the evenings and although immersed in his work and study, he remained very much a Man of Kent. Consequently, when the opportunity came to become William Blore’s assistant at Canterbury Cathedral Library he took it, and two years later, in 1948, he became Canterbury Cathedral Librarian and Archivist. The other major local collection came under his supervision three years later when he was appointed the archivist of the city of Canterbury. Such access to the wealth of documentary materials held in Canterbury gave him the chance to undertake his own research and he grasped the opportunity with both hands. Thus, although twenty years in the making, his great work that had begun under the supervision of Professor Vivian Galbraith came to fruition in 1967 as Canterbury under the Angevin Kings. However, as Bill noted, his father was also happy emulating Heath Robinson and his pride and joy was a Photostat machine he created out of biscuit tins, cat food tins and other ‘rubbish’.

For the family, life in early 1960s Canterbury was at times very tough due to William Urry’s health problems and the limited remuneration as librarian and archivist. This meant he was prepared to leave his beloved Canterbury to take up a Visiting Fellowship at All Souls College in Oxford in 1968 and the following year he was appointed as Reader in Medieval Western Palaeography and a Fellow of St Edmund Hall. Throughout his time in Canterbury and Oxford he was an acclaimed lecturer, but Bill thinks the best lecture he ever heard by his father was in 1970 at the University of Kent. Not surprisingly, this was on Becket’s martyrdom, and, as Bill said, what made it so special was the way his father drew wonderful word pictures that meant the excitement of his audience was palpable. Such memories are valuable because they help to bring William Urry alive, and the audience was extremely grateful to Bill for his personal insights.

Professor Louise Wilkinson discusses Angevin Canterbury

Keeping with Canterbury under the Angevin Kings, Professor Louise Wilkinson highlighted why this has been so influential over the last fifty years. She noted that the reviews had been very complimentary, including one by C. R. Cheney who said that William Urry had ‘done great service to Canterbury and to scholars, equalling William Somner [that great 17th-century antiquarian] in piety, surpassing him in learning and discrimination.’ She also described how perhaps mostly recently Dr Jake Weekes of Canterbury Archaeological Trust had used this work in his interdisciplinary chapter: ‘Residues, Rentals and Social Topography in Angevin Canterbury’ in Early Medieval Kent, 800-1220 (Woodbridge, 2016). As she said, Jake had drawn together material from the rentals and maps provided by William Urry and set this into the framework of the results from Canterbury Archaeological Trust’s excavations over the last forty years. This had allowed him to consider not only Canterbury’s wealthier citizens but also poorer people, those often ignored in historical studies.

The Magna Carta project benefitted from William Urry’s work

She also mentioned the way William Urry’s study had inspired one of her postgraduate students. For just like him and his interest in the Jews of Canterbury, Sophie had explored another ‘minority’ group when she undertook her Masters on women in Angevin Canterbury. This link between William Urry’s interests and those of researchers today also fits with Louise’s own work. As she explained, his interest in the way the local and national interlinked, whether he was discussing relations between Christians and Jews in 12th-century Canterbury or the relatives of Thomas Becket, is critical for her research too. In particular, the major AHRC-funded research project on Magna Carta had brought together these ideas in terms of the scholarly books and website, as well as the various exhibitions, including that at the Beaney, which in total had been seen by over 50,000 people. The exhibition in Canterbury had featured, among other exhibits, some of William Urry’s maps to illustrate the make-up of the city’s society in 1215.

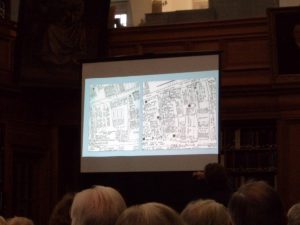

Paul Bennett demonstrates the value of William Urry’s maps

Another person who has benefitted from this book – the rentals, charters, maps and detailed analysis – is Paul Bennett. Unlike Louise, Paul had met William Urry a few times when he moved to Canterbury to join Tim Tatton-Brown at the fledgling Canterbury Archaeological Trust. Paul remember the magic that William Urry was able to weave as he recounted who had lived in the various tenements in 12th-century Canterbury. However, it was his published works that Paul has used the most, and he drew on the excavation of the Longmarket area of Canterbury to illustrate this. Almost at the heart of Angevin Canterbury, this block of medieval streets around the Butchery contained the workshops of some of the city’s wealthiest citizens. Probably the most famous is Terric the goldsmith, not least, because Paul and his team were able to excavate the very furnaces that Terric and his workforce had used for the smelting of silver and copper alloy. Even more stunning, the archaeologists had unearthed crucibles, as you can see here, as well as other finds such as pottery from Rouen, dwarf walls for the timber-framed buildings and clay floors for these same tenements.

Crucibles from Terric the goldsmith’s workshop

Other speakers provided further memories about William Urry’s time as archivist in Canterbury, including Margery Lyle and Professor Jane Sayers. In addition, his other publications were also remembered, such as his many articles for the Canterbury Chronicle and a series of booklets for the Beaney, as well as the two books published posthumously from his notes. The first of these was on the life of Christopher Marlowe, edited by Andrew Butcher, and the second on Archbishop Thomas Becket’s last days, edited by Dr Peter Rowe, who was in the audience. As President of the Kent History Federation, Peter is yet another connection between William Urry and the study of Canterbury and Kent history today.

Thus ended a fascinating afternoon, and, as Peter Ewart a professional researcher said afterwards, it had really brought the great man alive to those who had not been fortunate enough to meet him. Indeed, when I left there were still people reminiscing over cups of tea and biscuits, something that seemed very much in keeping because it appears such rituals had been part of the life of the archives when William Urry had been king of that domain.

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 2675

2675

Thanks, glad you enjoyed it. Sheila

I feel very sad that I knew nothing of this gathering for Bill Urry. He was my godfather, and I have many wonderful memories of him. He knew me as Cherrie Parrish. I am now known by most, as Jane Morgan. Bill and my mother grew up in Canterbury together, and I remember Bill’s mother meeting us in Littlebourne, during WW2.

I’m sorry to hear that Jane, I believe the event was organised by Cressida Williams at Canterbury Cathedral Archives in conjunction with William Urry’s children and they may not have known about your connection or how to contact you. I’m sure if you contacted Cressida she could put you in touch with the family. Sheila

Dear Jane Morgan,

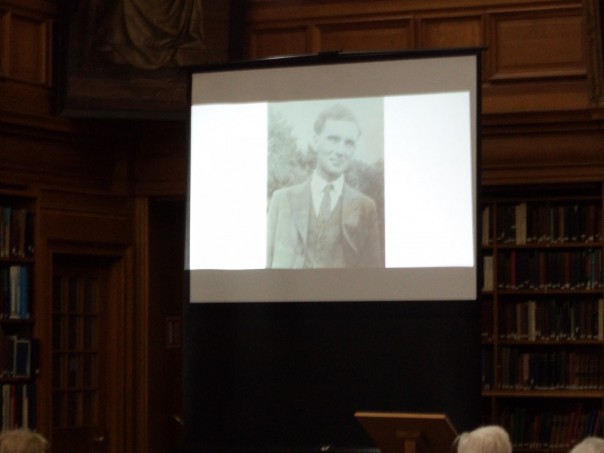

I now live in Winchester, where I found to my great joy a copy of Dr Urry’s book about Thomas Becket in Oxfam the other day. In the preface there is a very handsome photo-portrait of your godfather, but I think it must be mis-dated as it is obviously of a younger man than I recall from my own days as a schoolboy in the Precincts. For a start, his hair was longer and he invariably wore spectacles. Is there any chance you could supply me with a photocopy – no need to go to great expense: black-and-white will do – of how he appeared in the years 1961-1966 ? I’d gladly send a tenner for such.

Kind regards from Brother Adrian Risdon of St. Cross Hospital SO23 9SD

Dear Jane and Adrian, I hope you have managed to exchange addresses and information.

Did Dr William Urry ever write anything about his Family origins on the Isle of Wight?

Sorry Douglas, I don’t know but others may have more information.