This week I want to bring you a report on the first Faversham History Fair that I attended last Saturday, which was organised by the Faversham Society, because it gave me a chance to meet old friends and make new acquaintances, as well as sharing some ideas about medieval religion and the painted pillar in the town’s parish church. However, before I get to that this is just to let know that both the “Campfire Tales with a Canterbury Twist” and Saturn’s guest appearance at Canterbury Waterstones have been finalised: http://www.canterbury.ac.uk/arts-and-humanities/school-of-humanities/medieval-canterbury-weekend/medieval-canterbury-weekend-2018/chaucers-tales.aspx while Saturn’s event is free (see below).

Firstly, I want to tell you about the numerous array of stalls that were set up in the Alexander Centre. These showcased the work of numerous local groups, but I was especially interested in the Faversham Society Archaeology Research Group, the Maison Dieu Museum, the Faversham Society History Research Group, and the Invicta Seekers Metal Detecting Club, all of whom had amazing displays, often including artefacts. Moreover, members of the various groups were very keen to share their knowledge regarding such finds, and much more besides.

Saturn will be visiting Waterstones, Canterbury.

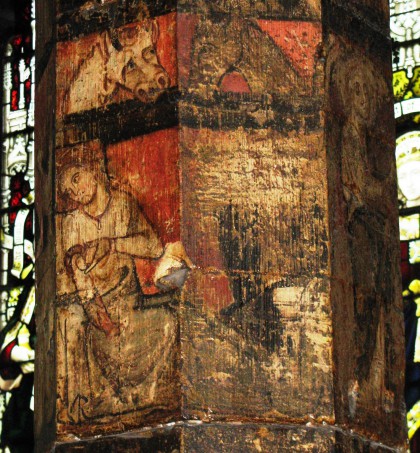

To return to what I see as the important points about ‘seeing and been seen’ with respect to the painted pillar, I think there is more to the paintings than a series of disparate scenes from Christ’s Nativity and Passion on three tiers around this octagonal pillar; that is six scenes from the Nativity and two from the Passion, with a third scene that could be either a tree or a vine. The two crucial topics, I think, are firstly the line of sight of either Christ or Mary his mother, and secondly what is on the west-facing side of the pillar: the top panel being the Crucifixion, below the Christ Child suckles from his mother as part of the Nativity, and at the bottom there is the Virgin and Child as the final panel of the Adoration of the Magi.

Rather than taking you through the whole sequence, I’ll just note a couple of these sightlines. Taking the Nativity scene itself, the painting of Joseph is now lost but the position suggests strongly that he would have looked left towards Mary and the baby, the scene completed by the ox and ass above which similarly face the centre. However, Mary looks neither at Christ nor at Joseph, but instead she looks down and to the right. This takes her and the viewer to the Adoration of the Magi, which at four panels is the longest of the Nativity sequences. This sequence finishes at Mary and the Christ Child on the west facing panel of the bottom tier. Here the crowned Virgin Mary stares out at the viewer, but the haloed Child does not. Instead he looks up and to the left to the altar on which he is presented in the final Nativity sequence: Christ Presentation at the Temple.

Faversham’s painted pillar – Mary suckling Christ (photo Imogen Corrigan).

The reason I’m interested in this relates to medieval ideas about seeing. The first of these considered that the eye actively saw by sending out rays that lighted an object to make it visible, known as extramission. Yet to a considerable degree this gave way to the idea of intromission where the image sent out rays that passed into the eye and then to different parts of the brain, thereby creating a dynamic relationship between subject and object. Added to this idea was that what was seen by the bodily eye was one thing; but could be transformed into being seen by the ‘mind’s eye’ which would reveal higher spiritual levels of knowledge, the desire of all devout orthodox medieval Christians.

Taking these ideas about sightlines, ways of seeing and the particular scenes on the west facing side of the pillar, which would all appear to have had strong Eucharistic connections, it is feasible there was an altar on this western side (see precedents at St Alban’s Abbey) and that it was the altar of Our Lady of Bedlam, thereby providing an important place of devotion to the Virgin Mary (one of many) in this church. If anyone is interested in exploring this further, I have an essay in S. Kelly and R. Perry, eds, Devotional Culture in Late Medieval England and Europe: Diverse Imaginations of Christ’s Life (Turnhout, 2014).

Among the other speaker was Duncan Harrington, who explored depositions from the church court records of the dioceses of Canterbury and Rochester. He is currently working on the records of Canterbury and he opened by telling the audience that this diocese has the greatest surviving collection of any in England, having an almost complete run of these records from 1411 to 1755, with only a few gaps. Unfortunately, just like the will registers, coverage within the Rochester records is far more limited, comprising two registers: dated 1541-71 and 1631-36, the rest apparently lost to neglect – damp, mould and disinterest.

Part of the Faversham Society Archaeologists display.

Even though we are presumably looking at what might be said to be a constructed narrative of events (see the blog last week), culturally this is still fascinating because witnesses needed to stay within the credible, as well as like any remembered narrative requiring its composer to make sense of what s/he thought happened. However, the main point Duncan was raising was the value of the deposition’s preamble where often such details as the age, residency and previous residency, and more occasionally occupation (more often marital status for women) of the deponent is recorded. Such information can be used in a variety of ways, for it offers occupational and age profiles, as well as yielding ideas about distances travelled by migrants, and perhaps even why some made the journey. Providing a Faversham case study, Duncan also demonstrated to his audience the advantages of these depositions, because they frequently reveal much about the lives of those in the neighbourhood, as well as the main protagonists. Thus, Duncan followed John Kybbett in seventeenth-century Faversham, painting a word picture of this man’s unfortunate last hours and the problems this caused regarding matters of inheritance for those around him.

Keeping with the idea of a man’s last hours, but in this case exploring what happened when this became the subject of a domestic tragedy, Professor Catherine Richardson and Dr Rory Loughname (both from the University of Kent) looked at the play Arden of Faversham. Catherine is in the process of producing a new edition of this play and, as Rory said, now that it is believed by scholars that William Shakespeare wrote some of the scenes, there is considerably more interest in the text. However, I’ll leave aside these textual revelations and instead concentrate on Catherine’s examination of what we know about performances. These seem to have been national (Covent Garden late eighteenth century) and local (Faversham – early eighteenth century, with revivals in the twentieth century) At least one of the latter productions took place at Davington Priory, Catherine showed photos of the cast performing various scenes, as well as in Arden’s house itself, that is where the actual murder took place. What was also fascinating was the tradition of performing the play using puppets, including the Fantaccino Figures in the 1820s, for which a publicity bill survives in the V&A archive collections. Furthermore, there is a papier mâché head of such a puppet in the Musées Gadagne that is quite sinister – amazing what people can do with paper, glue and paint! Nearer to home, the Faversham Society holds a puppet depicting Alice Arden and Catherine is hoping more information will come to light about this, as well as the local performances mentioned above. This was all extremely interesting, especially because I have taught the play in the past and will be doing so again in a couple of weeks.

Michael Frohnsdorff discusses the Maison Dieu’s seal.

Another talk I enjoyed was given by Michael Frohnsdorff, who was looking at a couple of historical questions about Faversham that he believes require further research. Due to limited time, he confined his remarks to two issues. The first being why King Stephen decided to establish an abbey at Faversham, for, even though it had been a royal manor, the king had previously given it to his most important military commander William of Ypres. Michael thinks the reason has far less to do with Stephen and far more to do with Queen Matilda of Boulogne, his wife. The critical issues from Michael’s perspective are her Saxon pedigree – through the Scottish royal line from Ethelred II, and that the abbey was founded at the time of the Second Crusade, her grandfather having been heavily involved in the First Crusade.

His second ‘mystery’ concerned ‘Was there a King Stephen’s Castle?’ Michael thinks the evidence suggests there may have been, and he places the site on the hill just off the A2 going out of Ospringe. He drew on several sources including Hasted, the early OS map and deeds from the Maison Dieu archives – a tantalising prospect, albeit the path of the railway means that the archaeology has all but been obliterated.

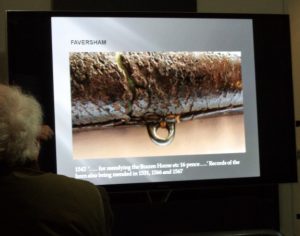

Canterbury’s ancient moot horn.

Angela Websdale (undertaking her PhD at the University of Kent) was another speaker and she discussed patronage and the wall paintings in the north chancel aisle chapel of Faversham parish church, the chapel dedicated to St Thomas of Canterbury. This was interesting but for my final speaker I want to turn to Dr Louise Bacon because previously I had only seen a couple of Kent’s moot horns and she provided a fascinating assessment of these often, ancient pieces of civic paraphernalia. Although she did include Canterbury’s moot horn because it is one of the earliest – dating from the fourteenth century, her principal focus was the Cinque Ports. She is studying the metallurgy of these horns, including matters of repair and decoration. Consequently, she is hoping to x-ray many of these horns to gain a better idea of how these repairs were carried out and what they may have covered up in the process. For the audience, Faversham’s horn was of special interest, and one of the factors that makes it especially noteworthy is the leather cover. Being a fourteenth/fifteenth-century horn, this cover has rotted over the centuries, thereby affecting the copper alloy horn underneath. As well as the moot horns themselves, there is such information about their use in the various chamberlains’ accounts and the town custumals, and very occasionally references to those involved in repairs, including details about what was done.

Leather cover of Faversham’s moot horn.

Thus, this was a fascinating day, both the displays and the talks, and it was great for the Centre to be present, the two universities working together. The need for such collaboration is critical, and in the final talk of the day Dr Ben Marsh (University of Kent) highlighted the dangers local history has been facing for some time, both in universities and in local communities. Yet, as he said, local history matters and after going through the challenges it faces he went on to highlight the values of good local history. For such detailed work can challenge assumptions about communities through the study of factors such as material culture. Moreover, as Magna Carta showed, these nationally as well as locally important documents can open up discussions in the fields of geography, environmental studies and history. This looking beyond the local allows historians of all backgrounds a means to bridge the gap between the familiar (mundane) and the wider world; or put another way to create a reciprocal relationship between the micro and the macro. Universities, too, have come to value such exchanges and even though the buzz words are inclined to change, impact remains one of the core issues academics are expected to pursue – of considerable benefit to the study of local history. However, grants are getting ever harder to gain, but whether crowd funding is really the viable alternative only time will tell. Thus, Ben gave his audience much to ponder on, but the fact that many of the talks were fully supported and there were people milling around the various displays all day does show there is an appetite for local history in Faversham, and beyond.

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 1510

1510