The first item I thought I would bring to you this week is news of the rescheduled Becket Lecture that will now take place on Tuesday 6 March at 6pm in The Michael Berry Lecture Theatre, Old Sessions House. As you may remember, the lecture will be given by Dr Marie-Pierre Gelin (UCL) and she will be speaking on ‘Thomas Becket and his Predecessors in Canterbury’. Booking not required, and we at the Centre will look forward to seeing you there.

Another development this week has been the finalisation of the ‘Maritime Kent through the Ages’ conference and the flyers for this have now been printed. The conference looks very exciting because as well as speakers known widely in Kent, such as Dr Gillian Draper, Dr Martin Watts, Dr Chris Ware and Dr Sandra Dunster, the line-up includes experts from Chatham Historic Dockyard – Richard Holdsworth MBE, and from Dover Museum – Jon Iveson, as well as an internally-important contributor to all things maritime in the Middle Ages – Professor Maryanne Kowaleski. Furthermore, to cap it all we are very fortunate that Dr Chris Young, a CCCU geographer, will kick off proceedings on Saturday morning by taking us through the environmental and topographical coastal changes and continuities that Kent has experienced over the centuries. The booking system will be in place early next week and then tickets will be available at www.canterbury.ac.uk/maritime-kent or you can email artsandculture@canterbury.ac.uk or phone 01227 782994. The Centre is again working with Kent Archaeological Society, and a new partner in the Royal Museums Greenwich.

The Mathew at Sandwich (photo Keith Parfitt)

Even though this conference on ‘Maritime Kent’ does not feature Canterbury specifically, the city’s importance on the road between London and the Channel Ports has long been recognised and then the quick hop over the Channel has meant there have been strong links between Canterbury and France, especially Normandy, for centuries. Probably at no time was this more important than the reigns of the Norman and early Angevin kings, and from an archiepiscopal perspective, with its associated monastic house of Christ Church, the appointments of Archbishops Lanfranc, Anselm and Theobald are worth singling out. This neatly brings me to my next topic for the blog this week, Dr Leonie Hicks’ lecture to the Canterbury Historical and Archaeological Society. As frequent readers of the blog may recall, Dr Hicks is a Senior Lecturer in Medieval History at Canterbury Christ Church who is especially interested in aspects of Norman landscape, and her topic on Wednesday reflected this research, which she hopes to write up as a book within the next twelve months. The focus this time was the foundation and early life of the abbey of Le Bec and the means whereby those in authority sought to create a sense of place for the abbey in time as well as space.

Yet this was somewhat of a tall order for the early abbots because unlike some houses in the region Le Bec had no Merovingian past that it could cite, and no great ducal or senior ecclesiastical benefactor it could laud. In fact, the abbey was established in the 11th century by a monk from the knightly class who could not find a monastery that he felt he could settle in. Moreover, Herluin was not a monastic scholar, and, at first, he seems to have wanted to lead a more eremitical existence, which was not valued at the time either. Thus, this was not an auspicious start and things didn’t get much better because Herluin and the fledgling community were not happy about their first location, and it took some time to find what would become their permanent site, a move along the valley that provided a location that was not too far from civilisation and offered them a source of fresh water – vital liturgically and for practical reasons.

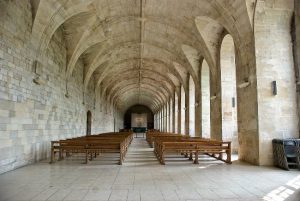

Abbey of Le Bec [https://media-cdn.tripadvisor.com/media/photo-s/0b/c0/2b/17/eglise.jpg]

Nonetheless, Herluin’s search was not in vain and for Gilbert Crispin, his biographer, the monk’s life offered a means to construct an exemplar that highlighted the importance of stability – the monk bringing balance between work and prayer for the sake of God and his brethren. And this was not all because Herluin had several prophetic dreams – a sure sign of his spirituality, especially because these too helped him to maintain the community’s stability. For example, in the case of Lanfranc he ‘saw’ him wishing to become a solitary, to which end he planned to leave Le Bec and live on thistles. Fortunately for the future primate having been warned in this way Herluin was able to stop Lanfranc from leaving and promoted him to the position of prior. Of course, with the benefit of hindsight this only delayed Lanfranc’s departure (and that of the monks he took with him) but it did set him on his career within the Benedictine monastic ‘family’ and for Crispin was a mark of Herluin’s importance.

Consequently, in life Herluin had brought stability as he created and maintained the monastic community around him and in death he would continue to do the same. For although the building of the abbey of Le Bec had taken quite a considerable time – not helped by several fires – as befitted his position as abbot Herluin was buried in the chapter house. Furthermore, succeeding abbots were buried around him, thereby placing him at the centre of the spiritual community, and, even though he was not a saint, he was to a degree taking on that role, his commemoration offering an esteemed founder and spiritual guide for the monks throughout the high Middle Ages.

However, as Leonie explained, this sense of stability through association with the monastery of Le Bec was not just a matter of physical location in the landscape because it was understood by all concerned that first Lanfranc, and then Anselm, took the spirit of Le Bec with them when they left for they continued to show a deep affection for their ‘old’ community. In Lanfranc’s case one way he demonstrated this was his act of consecrating the abbey’s new church in 1077, an event that brought numerous high-status guests who were honoured through the abbey’s gift of hospitality and the special liturgy that must have bombarded all the senses of laity and churchmen alike.

St Augustine’s Abbey, Canterbury

Drawing all these threads together, Leonie noted that even though there are gaps in our knowledge of the abbey’s history, texts such as Crispin’s ‘Life of Herluin’ offer historians today excellent insights about the culture of medieval Benedictine monasticism, the value placed on stability and community, and the role of memory in the construction of origin ‘myths’. These ideas had obviously interested members of the audience, and Leonie answered numerous questions during the subsequent Q&A session and after the lecture finished. In addition, David Lewes in his vote of thanks mentioned not only her very thought-provoking talk, but the way she had made it accessible and humorous. He had enjoyed it immensely, not least because he had been to Le Bec, which he liked, and he could vouch for the beauty of the place and its association with Canterbury.

Keeping with this Canterbury link, I thought for the last section this week, I would mention briefly a course I was running today for Canterbury Archaeological Trust. Of the seven people who gathered in the Trust’s library in Broad Street all bar one were from Kent, the seventh having come the considerable distance from Oxford for the day. Unlike the Trust’s usual courses, we were looking predominantly at documents, the purpose being to discover something about the lives of Canterbury’s townsfolk in the late medieval and Tudor periods. Using a thematic approach, we started with topography and a selection of old and new maps to think about, for example, the relationship between the town within the walls and the suburbs, looking at such matters as the road pattern, the location of markets, and landholding by the great institutions.

The Greyfriars, Canterbury

Governing the city came next and here young Thomas, who is only 11 years old, did a splendid job of describing the city’s seal with the castle on one side and a representation of Becket’s murder on the other that then provoked a lively discussion respecting matters of civic status and how the city was under royal and saintly protection, a message that would have been understood by outside authorities who received documents sealed with the city’s seal. We also explored the advantages of being a Canterbury freeman, including the right to hunt, fowl and fish within its jurisdiction, before turning our attention to the city’s decidedly diverse property portfolio that included wall towers, shops, inns, gardens, houses and the odd cellar.

Thomas showed great staying power and fortified by sausage and chips at lunch time, he was ready to tackle such documents as the intrants’ lists (those below the freemen who paid fees annually to be able to trade independently in the city), a will and a couple of inventories. The intrants’ lists start in the early 1390s and the group were interested to see the range of industries such people had been involved in, as well as the presence of at least two men from the Low Countries. The inventories were from two centuries later and while Agnes Cobbe had definitely been a prosperous widow, Joan Stredwicke had been decidedly poor. Having counted up the number of rooms in Agnes’ house, Thomas and the rest of the group were interested to note that there were beds in every room bar the hall and kitchen, including a truckle bed in the parlour. Agnes also had a very considerable amount of napery and clothing in numerous chests and a possible reason for this became apparent through the list at the end of the inventory of those who owed her money for she was acting as a pawnbroker and money lender. On the other hand, poor Joan’s assets were decidedly meagre, and the appraisers were seemingly hard pushed to find enough stuff in her place to cover her debts.

Studying Medieval and Tudor Canterbury.

Parishes, religious houses and pilgrimage were not for Thomas, and he and his dad decided to stop at the afternoon tea break. The remaining attendees examined documents from St Dunstan’s church just outside Canterbury’s liberty, including a very long and detailed inventory as a way of exploring what the church looked like – the altars and their dedications; ideas about the range of church books that were not only liturgical but also included saints’ lives; and the likelihood of a choir that included boys, and thus the presence of polyphonic music. Before leaving St Dunstan’s we looked at some photos of the place where the ‘idolotrious’ steps had been removed as the Reformation unfolded and the communion table replaced the high altar, as well as the changing focus towards the pulpit.

Finally, having briefly run through the diversity of religious houses in Canterbury, we spent some time discussing pilgrimage before and after 1170. In particular, we examined the complexity of time and space whereby the cathedral monks were able to provide for the many pilgrims as well as ensuring that the rich liturgical life of the monastic community could continue without interruption. This seemed a good place to end the day – the city’s most important ‘industry’, and we finished by looking at some Becket pilgrim badges and how the makers in producing these various designs may have had a good eye for business opportunities. Thus concluded, our thematic study of late medieval and Tudor Canterbury and I hope those attending enjoyed the day too. Moreover, it was great to hear that some have already booked to attend events at the Medieval Canterbury Weekend in April later this year.

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 512

512