Looking at the Canterbury and Rochester diocesan archives and ‘The Clerical Estate’

On the grounds that we are nearly at the end of September, I thought I would give you an update on progress regarding getting the Medieval Canterbury Weekend 2020 up and running. Much of the website is now done and I just need to supply a small amount of information to Matthew Crockatt, our great IT/web organiser. There are some other internal CCCU hoops to get threw too, but I’m still hoping that we can make it live before the end of October, and, as soon as it is, I’ll post a notice in the Centre’s blog.

This brings me back to this week and as last week I’m going to be reporting on two events, but this time both are conferences in which members of the Centre were involved. The first happened on Saturday at the Kent History & Library Centre at Maidstone and was organised jointly by Sarah Stanley and Dr Mark Bateson. As some Canterbury archive users may remember both Sarah and Mark worked at Canterbury Cathedral Archives and Library before the split in Kent archives and the more separate existence of the county and Canterbury records.

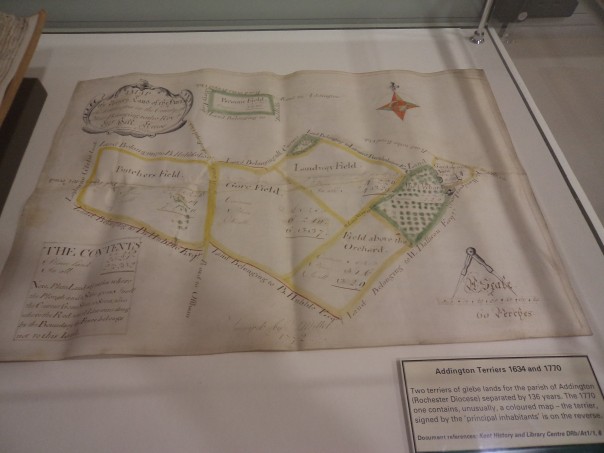

To return to the conference, this was to mark the bringing together at Maidstone of the Canterbury and Rochester diocesan archives, and to showcase the types of research these collections have enabled both academics, and family and local historians to undertake over the last twenty years.

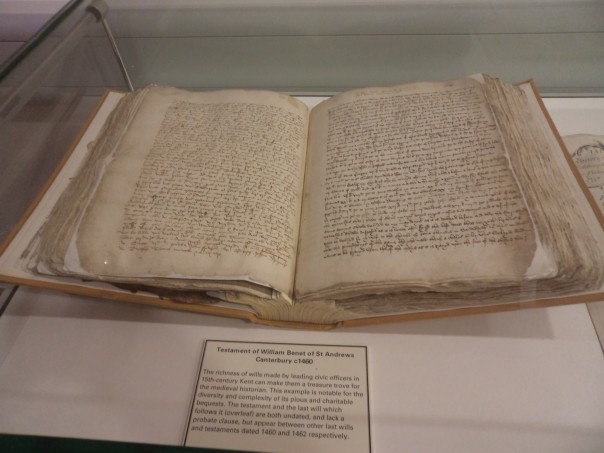

After refreshments on arrival, Mark introduced the day’s proceeding by giving a brief overview of the dioceses, for, as he said, Kent is extremely unusual if not unique in that it comprises two dioceses and their archives are now completely under the custodianship of a county government authority. Among the jewels in this archival crown are the 434 volumes of church court records for Canterbury starting in 1364, the probate materials for both dioceses, albeit Canterbury’s is more extensive in terms of 15th and 16th-century wills, and the bishops registers from Rochester which run for almost 600 years from 1319 to 1903. Perhaps more unusual are the reused medieval parchment fragments that are to be found as covers and elsewhere in later manuscripts, including an early 10th-century copy of Priscian’s Institutiones Grammaticae.

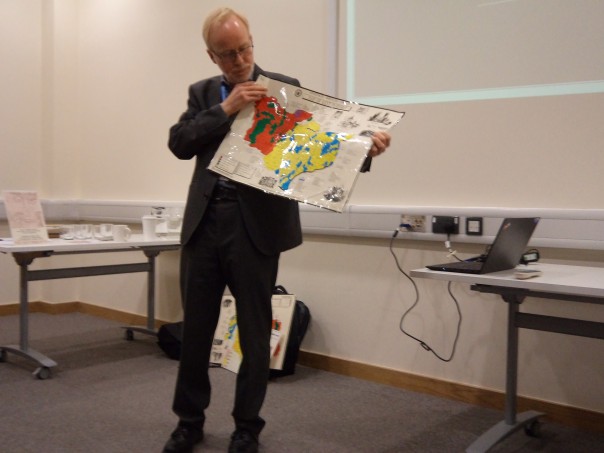

With this background information, the audience welcomed Professor Kenneth Fincham who started by saying that the Church of England Clergy Database is now 21-years old, having benefitted from two AHRC grants. Furthermore, there are moves afoot to try to secure extra funding to update and secure its future for new generations of historians to use. Among the 50 archives the original team of researchers used was that at Maidstone, and of the series deployed to people the database was the Libri Cleri. As Kenneth explained, these visitation lists include matters such as details concerning ministers and schoolmasters, and even more importantly curates, who otherwise are extremely difficult to track down in the records.

The database has been a very useful resource for a wide range of historians, including some of the other speakers. Moreover, this has been a 2-way process because some users have alerted Kenneth to new material, discrepancies, as well as helping to make some of the identification of certain individuals more secure. For, as he commented, it is important to realise just how mobile some of these clerics were during their careers, often moving among several dioceses. As a 17th-century specialist, Kenneth is interested in the state of the Anglican Church in the 1640s and 1650s, albeit there are no diocesan records, which means Archbishop Sheldon’s ‘survey’ of what was happening at parish level in 1663, following the imposition of the Restoration, is an amazing find. Thus, diocesan records have been key to the creation of this relational database and Kenneth hopes that this resource will continue to be used by historians for years to come.

Taking a different approach, Professor Catherine Richardson, drew on several different types of record to explore how it is feasible to bring early modern households to life. Catherine is especially interested in the lives of the ‘middling sort’ and for this large group within society the most helpful diocesan records are inventories, wills and church court depositions. This area of research is something Catherine is now engaged in as part of a large AHRC-funded project, working with colleagues at the universities of Birmingham and King’s, London.

For the purposes of illustrating how such research can be conducted, Catherine concentrated on a disputed probate case relating to the death of John Williamson, who died in the house of one of his sons-in-law located within the precincts of Canterbury Cathedral. As she said this case was valuable because it demonstrated a number of different points, such as the way death brought discontinuity within the household, the early modern desire to manage death carefully through the giving of instructions, whether in appropriate texts or by the speech and actions of those at the deathbed, and the timing of the tolling of the parish bell to mark the point of death. Moreover, this critical moment had both spiritual and legal ramifications not only for the dying but for those who did/didn’t gather at his/her bedside – family, friends, neighbours. And where deponents were required to testify what happened to the court, there was the added layering of narratives, issues surrounding memory, and the status/honour and credibility of witnesses. Weaving her way through the different documents to draw together the salient threads, Catherine was able to illustrate just how rich these records are and how much they can reveal about domestic and commercial spaces, the objects to be found there and, probably most usefully, how contemporaries understood and deployed these same objects and places in their lives.

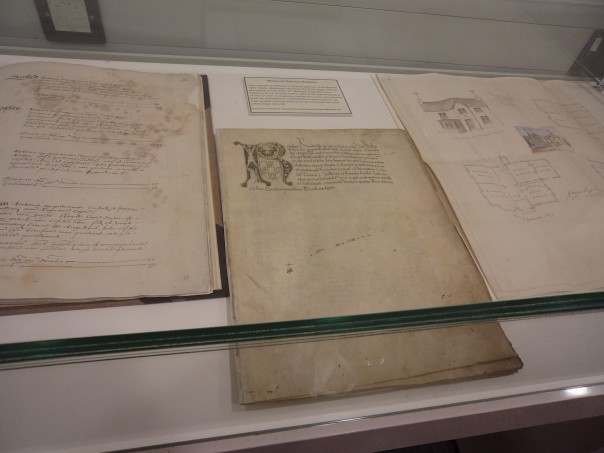

Following a short break, Dr Timothy Brittain-Catlin, the third speaker from Kent University, showed how useful the diocesan sources are from those within the archives of Queen Anne’s Bounty. The desire by the ecclesiastical authorities in the early 19th century to improve the housing stock of Anglican parish clergy led to mortgage applications to fund such improvements as better internal drainage, renovations of run-down properties and the designing of whole houses. As part of the process detailed architects drawing were produced, probably for the first time and this initiative coincided with changes in design from Georgian (symmetry) to Victorian, including the Gothic revival. Many of this new breed of architect had been engineers which meant, for example, that drawings were to scale, and they had a much greater working knowledge of materials. Furthermore, there was a need for detailed specifications to ensure that projects were properly costed, and payment was only given once the finished building had been signed off.

From Timothy’s viewpoint, as a Reader in the School of Architecture, all these factors mean that the drawings in this archive are an absolute gold mine of information. Indeed, not only to they offer valuable information about changing styles of domestic architecture below the elite at this critical point in the history of architecture, but many of these clergy houses were renovations of medieval houses, which can be ‘seen’ within the drawings. In addition, a considerable number of these properties no longer exist or have been modified again in the last 200 years. Timothy illustrated his talk with several drawings, and like other speakers he had suggested examples that Mark and Sarah had put on display for attendees.

The second speaker in this session was Celia Heritage, a professional genealogist who is also extremely interested in local and church histories. In 2013 she published a book on tracing your ancestors using death records and it was this area of her work that she highlighted in her talk. Concentrating most on the value of wills, Celia took the audience through the ways these records can be used to help pinpoint death and burial; to help construct a family pedigree; to substantiate other information, and to provide all sorts of other useful information.

Turning to wills and local history, Celia underlined their importance when seeking to investigate house histories, for example. This is especially the case where inventories survive because it would appear appraisers often worked their way through the house moving from room to room where they noted down the contents, sometimes down to the old lumber. Consequently, such records can provide ideas about the workplace as well as the domestic, thereby helping to depict everyday life.

To illustrate these ideas, Celia drew on several modern and early modern examples and then moved on to thinking about wills as providers of information about the church, drawing on late medieval wills at this point. She is a resident of Ivychurch, one of the Romney Marsh churches and she had an example from that parish because it includes the testator’s desire for burial in the Lady Chapel. This chapel survives and the floor is very uneven, showing the location of such burials and Celia would like to undertake a project to investigate this further. The PCC are also interested but so far this project is at an early stage because there is a local history exhibition in the chapel and such works would need permission. However, it may yet take place!

After an excellent sandwich lunch, Mark talked further about these archives, specifically how they are catalogued and thus accessed by researchers. Then Dr Paula Simpson (Wren Library, Trinity College, Cambridge) explored the involvement of women in 16th-century tithe disputes using the Canterbury diocesan court records: Instance Acta and Deposition Books for both the Archdeacon’s and Consistory Courts. As you would expect women were far less involved compared to men as both plaintiffs and defendants in such cases, but they were there! For example, Alice Turner, the farmer of the rectory of Whitstable was especially litigious, bringing 11 cases in a four-year period from 1584. Similarly, a slightly higher proportion of the defendants were women, including one in a dispute instigated by the same Alice Turner.

Yet it was as deponents that women were proportionately more active in these cases, and while still a minority it does show, as Paula highlighted, that women were involved in 16th-century society as tithe payers themselves and were frequently present when tithe was discussed, whether in the fields, houses, churches or streets. Paula drew on a series of examples to illustrate the points she raised, but I’m just going to mention one. The case of Henry Grene (1550) shows just how men might pass the authority to pay the household’s tithe to their wives. As a parishioner at St Dunstan’s next to Canterbury he was reported as saying in court “he was a dyer and dyd medle with nothinge but his crafte and did suffer hys wife to medle with all other thynges aboute the howse, and so to pay the tithes.” Thus, as she said, women were apparently involved across the board in the tithe system, and the authority of communal knowledge might be invested equally among the elderly women as it was among the aged men.

Finally, I took the audience back to the medieval records to take another look at wills, this time in terms of exploring what they can tell historians about late medieval piety. For even though these are significant caveats regarding the employment of wills because they are deceptively seen as ‘personal’ documents, I contended that if used by combining quantitative and qualitative methods – that is a will(s) in context, they can be hugely informative.

Having run through the available databases, calendars and listings for Canterbury and Rochester, and given some ideas about the availably of wills up to 1540 by town or parish across Kent, I turned briefly to the structure of these last will and testament documents before exploring the will of William Benet of Canterbury regarding his pious and charitable bequests. To do this, I introduced the concept of the spiritual economy from the work of Professor Robert Swanson through the deployment of gift-exchange and reciprocity as the basis means of exchange. Added to this were the ideas of allocating these bequests under a system of parochial (gifts to the testator’s parish church as an entity), sub-parochial (to parts of the church, for example, specific images), and extra-parochial (religious houses of all kinds; and this can also take in bequests for the benefit of the community, including charity to the poor). Again, there isn’t space to have more than one example so perhaps something that seemingly encapsulates many of Benet’s ideas is his instruction to his executors that they should spend £10 on pewter ware, thereafter giving poor newly married couples – symbolic of the bedrock of the city’s next generation of skilled workers – 4 platters, 4 dishes and 4 saucers.

After a final round-up of questions, Mark thanked the speakers for all their efforts and the audience members for their enthusiastic participation. Then, while a few people decided to have another look at the fascinating documents Mark and Sarah had put out, and others came to talk to the speakers, the rest headed home after a thought-provoking and exciting day exploring the potential of these diocesan records.

My second event this week is a conference organised by Dr Rebecca Warren (University of Kent) with Professor Peter McCullough (Lincoln College, Oxford) to honour Dr Andrew Foster who is a remarkable historian of the early modern clergy. Having reached his 70th birthday and having joined Lincoln College as part of their ‘Lincoln Unlocked’ project, it seemed a fitting time and place to mark Andrew’s many achievements as an esteemed scholar, mentor and friend of many in this field. Consequently, there was a full day of excellent academic papers, a fascinating exhibition in the college chapel, and for those able to stay on, an enjoyable dinner in the evening. The speakers and chairpersons were a roll-call of the great and the good in this field of the ‘Clerical Estate’ and among these was Professor Jackie Eales. So chairing the session involving Jackie and Dr Silke Muylaert (who completed her doctorate at Kent under Andrew’s supervision), I heard about the social identity of the clerical family in early modern England as Jackie explained how education was a key feature of their lives. Moreover, this was not confined to the parsons’ sons but also to their daughters, and in many cases their wives, who were frequently the daughters of clerics, having benefited as children.

There isn’t space to do justice to Jackie’s paper or the many other fascinating talks, but I thought I would end by saying that this was a great day and seemed just the right way to honour Andrew – well done to all concerned, and especially Rebecca and Peter.

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 1452

1452