It really will be a short blog this week because it is in some ways a slight breather before a very hectic time next week that has several meetings, two conferences and a workshop. Nevertheless, this week has seen Dr Diane Heath and her co-producers getting to the final stages on their ‘Medieval Animal Magic’ booklet for primary schools, while Professor Louise Wilkinson has been busy working at The National Archives and giving papers, as well as attending Exam Boards – it is that time of year!

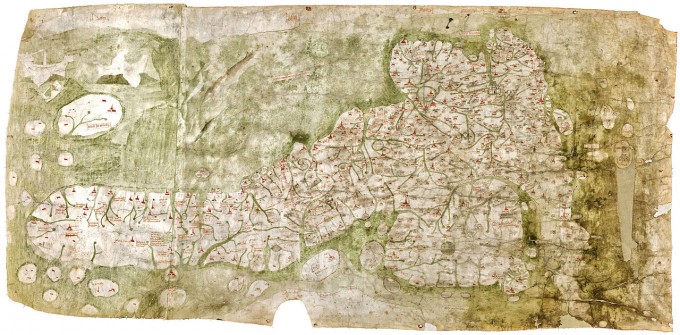

However, I thought readers might be interested in one of three meetings I had this week. That is sandwiched between the Kent History Federation and the Kent Archaeological Society, I had an exciting meeting with Catherine Delano-Smith and Damien Bove about their new Leverhulme-funded project on the Gough Map. For those who don’t know it, it is a fascinating late medieval map of England, Wales and Scotland that is at the Bodleian Library, Oxford. This is what it says on the Bodleian website: “the Gough Map, one of the great medieval treasures of cartography, arrived at the Bodleian Library in 1809 as part of Richard Gough’s bequest, an eighteenth-century antiquary and expert on British Topography. Richard Gough acquired it for half-a-crown on 20 May 1774 at the sale of the collection of Thomas Martin of Palgrave, where it was offered as Lot 405 and described as ‘a curious and most ancient map of Great Britain’. Dated approximately 1360, it is the earliest surviving map to show routes across Britain and to depict a recognisable coastline.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gough_Map#/media/File:Gough_Kaart_(hoge_resolutie).jpg

The map, measuring approximately (height) 553mm by (width) 1164mm, is drawn on the flesh-side of two pieces of sheepskin parchment, joined vertically. The lap-join was held together originally with a plain running-stitch, clearly identifiable by sewing-holes and thread-indentations along the join. Indeed, the thread interrupted the application of the green wash which represents the sea, indicating that the sewing was in place before the map was painted. The two parchments are now joined by adhesive only. The left-hand skin, seen in transmitted light, has the anatomical features of what appears to be the backbone and ribcage of a lamb.” [ https://www.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/bodley/about-us/conservation/case-studies/gough-map ]

This is a useful starting point, but the project leaders: Dr Catherine Delano-Smith, Nick Millea and Damien Bove think the map dates principally from about 1400 and that the map should be seen as a three part production, the first two phases very close in timing with the third quite a bit later into the 15th century. Their preliminary findings, involving the work of several other experts on pigment analysis and other technical areas, was published in Imago Mundi in 2017, and now they will be leading another group of scholars who will be exploring different regions on the map, for example Professor Nicholas Orme is looking at south-west England and Professor Chris Dyer is examining the west midlands. Other experts are similarly involved looking at the map in its entirety, including those working on place names, palaeography and diplomatic, and the map’s political context. I’m due to do Kent and Surrey, with the idea that the other two south eastern counties of Sussex and Hampshire will be covered by Dr Mark Gardiner (University of Lincoln).

Rochester Castle – a town on the Gough Map

From my perspective, even though I had looked at their published article and at some images of the map, the meeting gave me the opportunity to find out exactly what Catherine is looking for and to discuss what the map does/doesn’t depict. For like most historical documents, what is ‘missing’ is often just as significant as what is there. Taking Kent, for example, yes there are the two episcopal cities of Canterbury and Rochester, but the buildings used to show the city are bigger for Rochester than they are for Canterbury, although both are shown as walled. Fine, all the head ports of the Cinque Ports are there in both Kent and Sussex, as are the Ancient Towns of Rye and Winchelsea, but no sign of Lydd or even more oddly of Folkestone. Looking inland, among the places shown are Ashford, Maidstone and Tonbridge, but no Wye nor anywhere in the Weald, while along the north coast Faversham is present, as is neighbouring Ospringe but then going west the choices are Sittingbourne, Rochester and Gravesend, with Dartford shown as a church but not named. The mapmakers apparently not interested in the ancient royal town of Milton as one obvious omission.

Cobham College – a town not on the Gough Map

As well as settlements, rivers were seemingly equally important to the mapmakers, and these are for the most part reasonably accurately portrayed. However, as Damien said, there are only 5 bridges shown on the whole of the map, which is intriguing. Nevertheless, one of these is Rochester Bridge. I’ll need to think about this some more, yet in many ways I’m not surprised because the map post-dates but not by a long way the construction of the new Rochester Bridge, which was an important political and strategic project.

The Gough Map is famous for its apparent ‘network’ of red lines with distances between settlements. Kent only has one of these – going between Canterbury and Southampton at its furthest extent. In the past, these have been equated to roads or important routes, but Catherine and her team have discounted this and are exploring other ideas about why they were drawn, so more on this as time goes on.

Guildford Castle – a town on the Gough Map

I know I haven’t got to Surrey, but this part of the map is similarly currently throwing up all sorts of questions. Nevertheless, I hope this very brief discussion has got you intrigued about the map and its format, and I’ll keep you posted on future developments and ideas, but now it is back to aliens in 15th-century Canterbury.

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 2818

2818

Hello there. I am trying to find the route taken by King Harold as he marched down from Stamford Bridge to fight William at Battle. In particular, the possibility of the route down towards Tonbridge. The road from Sevenoaks to Tonbridge has a section beside theB245 which is referred to locally as Harolds route. It would be interesting to know. I reckon they were still following Roman roads for part of the journey….

Hello Elizabeth, thanks for this, an interesting idea and perhaps others would like to comment. I think the Gough map was probably seen by its creators was more about placement ie setting places (towns) in the landscape than about movement through it.

Best wishes, Sheila