To report, although decidedly wet in the West Midlands, the day went extremely well for all concerned (see last week’s blog), and thanks to Diane, yes, we have seen the photos. Dr Heath, as you can imagine, is now back into dragon-building mode and she and Dr Pip Gregory with student helpers have continued to make progress this week. Sadly, I had to miss Wednesday due to other commitments.

For this week, I’m just going to mention four other events directly involving the CKHH before reporting on two lectures where either CCCU or CKHH had some input. Working chronologically, I met up with Dr Rachel Koopmans and Leonie Seliger in Canterbury Cathedral’s Glass Studios on Monday to discuss with a further potential sponsor the next stage of the Becket Miracle Windows project. Although this meeting was focused on the windows as a discrete entity, Rachel, Leonie, Dr Claire Bartram and I have not given up on the idea of bringing visual and written cultures together in our ‘Exploring Becket’s legacy in text and image’ as an interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary project. Consequently, currently our efforts are focused on the stained glass windows, although as a complementary element, I am exploring different avenues for the Becket manuscript section. For the window element, early days but we are hearing encouraging noises, and hopefully as things develop, I’ll let you know our progress.

The second meeting was online involving Dr Craig Lambert and Dr Gary Baker (University of Southampton) and me concerning our funded project on ‘Kent’s Maritime Communities’. The various strands seem to be coming along very well as Craig and Garry test the database to run queries successfully using data collected from Tudor customs accounts, port books, taxation and muster rolls. I do sympathise having worked on the Sandwich project database a decade ago, because trying to deal with diverse types of evidence is challenging. For this project with Craig and Gary, I am far more concerned with qualitative material from the regional archives – Clifford Geertz’s ‘thick description’, which, as well as feeding into our multi-authored project book, will provide the means to explore how immigrants started a new life in these coastal communities, as well as in places such as Canterbury during the later Middle Ages.

Thirdly, as a member of the Lossenham project steering group, I joined the group for our monthly meeting, this time at Newenden. It was extremely interesting to hear how the archaeologists of Isle Heritage CIC with their volunteers are progressing – well it would seem for our understanding of the layout of the friary and being able to investigate the church in this way is excellent. Dr Rebecca Warren and I contributed by explaining how plans for the Lossenham Priory Study Day are progressing. We should have most if not all the draft texts and images for the exhibition banners from the volunteers in the wills group by the 1st July and numbers of our invited audience are going up steadily. For what you might call the creative and artistic side to the Lossenham Project, Russell Burden, the project’s artist in residence reported that he has been busy, and among his many projects are those centred on responses to the area’s geology. As a bonus, after the meeting Rebecca and I came back via Sandhurst church, which was fascinating. We went there because she is using Sandhurst wills for her presentation as part of the September Study Day.

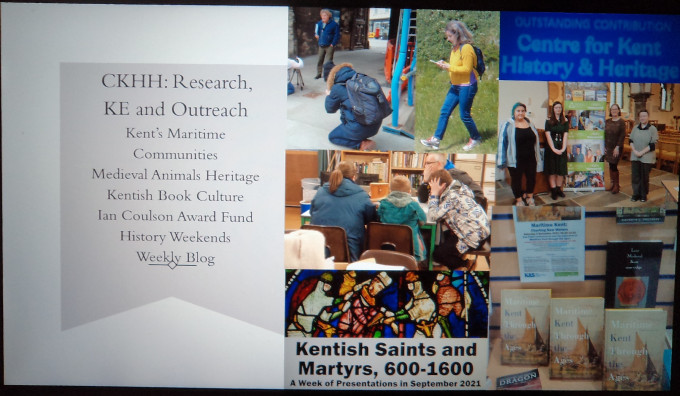

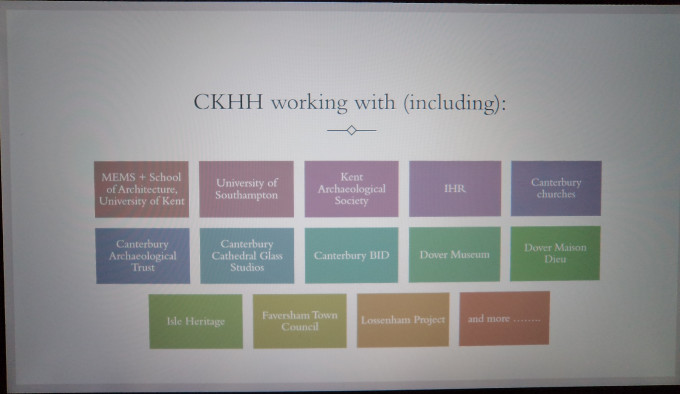

The last meeting before I get onto the lectures took place on Thursday when Dr Claire Bartram and I, as part of a Faculty initiative, outlined some of the CKHH’s activities involving outside partners. It is only when you sit down to prepare such a presentation that you realise just how many people and organisations the Centre continues to work with. I was reminded of this last weekend when I visited the new Faversham Charters and Magna Carta exhibition with a friend because CKHH had been involved in this project from the start and it is brilliant to see how it has come to fruition. Another such collaboration will be taking place again soon because the CKHH will be at St Paul’s church on Saturday 2 July providing family-friendly medieval animals-type activities as part of the Medieval Canterbury Pageant.

So now to the two lectures starting with Dr John Bulaitis’ (CCCU History) talk entitled ‘Tithe Warriors’ at the Kent History and Library Centre in Maidstone, I am borrowing Dr Mark Bateson’s (archivist at KHLC) report for this because unfortunately I couldn’t get there. Thus, as Mark says:

“Most European countries abolished tithe soon after the French revolution. The government of this country eschewed such a radical move, preferring to try to improve the system with a series of reforming Acts of Parliament. These failed to prevent spikes of unrest during periods of economic difficulty. Notable episodes of strife over tithe began with the Captain Swing riots, such as the ‘Bread or Blood’ protests at Wrotham in 1830. The Whig government then responded with the Tithe Commutation Act of 1836, which replaced payment in kind with an annual rent charge based on the price of wheat and barley. But further conflict ensued in the 1880s and 1930s. Public auctions of tithes in kind, distrained for non-payment, became a major flashpoint for physical violence, as auctioneers were jostled and attacked and the auctions badly disrupted.

John Bulaitis has been working on this subject for some years. His latest paper illustrated the fruits of the detailed research in local archives and among local communities, and a monograph is in preparation. The conflict and violence were dubbed ‘The Tithe Wars’ in the contemporary Press and in his talk, John focussed on two of the leading protagonists, or ‘warriors’. In one corner, Frank Allen, sometime Canterbury Cathedral Chapter Clerk and Tithe Collector, ‘the gamekeeper turned poacher’ who soon after beginning his tithe collecting role decided it was both unjust and inefficient. He became the Secretary of the Tithe Payers Association and spent the rest of his career supporting farmers in their passive resistance to the payment of tithe. And in the other corner, a man who rejoiced in the name of Edward Whitred Iltyd Peterson, the son of the rector of Biddenden, a solicitor who helped has own father with tithe collection and who became Secretary of the Tithe Owners’ Union. Peterson’s passion equalled Allen’s, from the opposite side of the argument. He vigorously advocated for the rights of the Church and other tithe owners to collect tithe and personally involved himself in tithe collection. He even volunteered to go to Wales (whose rural communities were experiencing a similar conflict) to help owners collect disputed and withheld payments there. The resistance to payment of tithe in Kent expressed a fascinating reversal of the normal political polarities. Here, the deeply conservative farming community organised itself into the sort of coordinated movement associated with conventional trade unions, and found itself in direct conflict with that pillar of the Establishment, the Church of England. John’s book is eagerly awaited.”

Now to the second lecture, working with Sue Palmer (churchwarden), Martin Ward and the Rev. Jenny Walpole (curate), it was great to be able to welcome Dr Rachel Koopmans and an in-person and online international audience (viewers from across the United States and Canada) to her lecture on the Becket Miracle Windows. She and Leonie Seliger (head of the Glass Studio) have almost finished working on nIII and are now looking forward to the next stage of the project, hence it seemed a great opportunity to hear what they have found. To introduce her subject, Rachel gave her audience of around fifty people in the church – testimony to her popularity considering it was a beautifully warm summer evening – an outline of how the Becket Miracle Windows are arranged around the Trinity Chapel and the common features such as the loss of the bottom panels to iconoclasts, probably especially during the mid-17th century. She also noted that almost totally lost is the glass from the two windows devoted to Becket’s life, except for one panel now in the United States!

Turning to nIII as the window featured in the British Museum Becket exhibition last year (literally centre stage, which had meant the BM had funded the removal of the window from the Trinity Chapel) and the current focus of conservation and study, Rachel took her audience through the stages of work during the intense 5 months she and Leonie, with the Glass Studio team, worked on the window, seeking to unlock its secrets and adopt the latest techniques in terms of good conservation management.

The first stage of the process was to examine and evaluate every single piece of glass, and there are literally thousands! They needed to ascertain which were medieval pieces that belonged in the panel, which Victorian or even later replacements, and which were medieval pieces but not from the panel they now sit in, the ‘stop-gap’ pieces. Thus for each panel they were able to produce working restoration charts (as for the first window, these will be enhanced and form part of the various publications on this window). As you can imagine, this all needs to be done carefully and Rachel estimates it took half the time allotted to the window. Similarly vital to assess is the degree of paint loss on each of the pieces, for the medieval glaziers were fantastic artists and the way they paint emotion into the faces, the folds of clothing, and animal features onto the coloured glass is just brilliant. Some glass pieces have hardly deteriorated at all, but some have lost a great deal and all of this information is providing vital clues about medieval craftsmanship and working practices, about the identity of the various pilgrims portrayed, as well as what has happened to the windows over the centuries. For Rachel and Leonie, one of the beauties of working on a series of windows is that they are developing diagnostic techniques, as well as getting an intimate knowledge of the cathedral’s former glaziers.

An area that especially pleases Rachel is the strides they have made regarding the inscriptions on the panels. Today most visitors don’t give them a second glance, even if they notice or can even see them at all on the higher panels, but on the studio bench and with the use of a torch and raking light, they are literally coming back into view. And they are offering fantastic new interpretations, as well as displaying how each of these narrative panels has a rhyming hexameter inscription. These, Rachel thinks, provided the monk guides with what we would see as a crib sheet to be able to expound the narratives just as they are in the miracle stories collected by Benedict between 1171 and 1173. Just as an aside, Rachel has now translated all of Benedict’s miracle stories and her edition will be going off to the publisher very shortly.

Taking all of this together, Rachel and Leonie have taken a giant leap forward for our understanding of nIII. For in 1981 when the ‘go-to’ catalogue was produced, most of the identities of the pilgrims in this window had a question mark attached and in some sections there were thought to be panels from different narratives jostling next to each other with little or no narrative sequence at all. But now we know differently! The window has 5 coherent and complete stories, and what is more Rachel can understand why these stories were selected, demonstrating that the priory and glaziers knew exactly what they were doing as a way of fostering the growing cult in the early 13th century.

Next Rachel went through three of these stories: Goditha of Hayes, a woman with dropsy; Ralph of Longueville, a leper, and look out for the wyverns; and the lame sisters of Boxley that highlight the significance of place as well as identity of what might be termed ‘ordinary people’ journeying through rural as well as urban space. However, I’ll leave you to discover Rachel’s findings because as well as livestreaming the lecture, it is now available to view at: https://www.dunstanmildredpeter.org.uk/livestreaming and it works, I tried it this morning.

What I do want to reiterate is the particularity of the stories (and pilgrims) selected – where they were from (mix of regional and national, possibly even from mainland Europe) and the range (and choice) of the ailments, and why all of this mattered.

For this brings me to the final part of Rachel’s talk – where next because nIV is slightly earlier than nIII being produced at a very specific point in the history of the priory and the development of the cult. Consequently, the choice of seemingly all Kentish miracle stories (Rachel and Leonie, like those before them, cannot yet identify the pilgrims in the highest panels, they need to see them up close) is significant. Similarly, the design and quality of the backgrounds for nIV is unique among the surviving windows. Thus, these and many other important research questions, including ideas about the history of medicine will be tackled once funding has been secured and the next phase of this project begins.

After her stunning lecture the applause was long and she then answered a whole raft of good and probing questions from the audience. However, now we must bid farewell to Rachel who will be leaving for Toronto next week, but she hopes to come back very briefly in the autumn and she will be working on the publication side of the project back in Canada.

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 1741

1741