It’s #TimetoTalk Day and Principal Lecturer Anne Cooke, at the Salomons Centre for Applied Psychology, explores the topic of mental health problems and in particular psychosis.

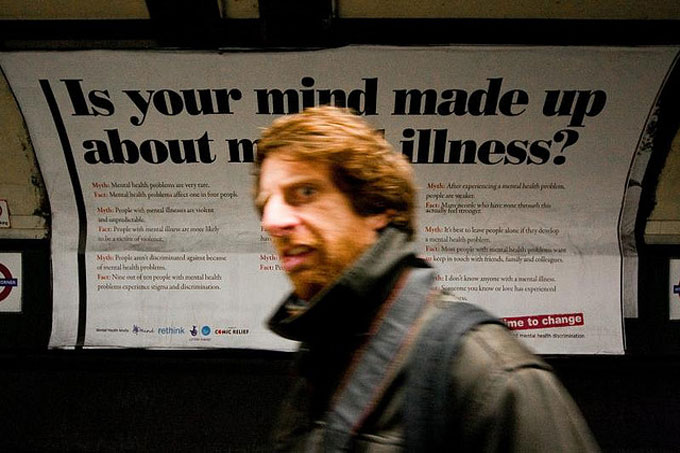

Today is Time to Talk Day. The idea is to encourage us to share our anxieties and mental health problems. And whatever your views on the monarchy, hats off to William, Harry and Kate for leading the way with their own openness and their Heads Together campaign.

In an ideal world, there would be no need for today. Why don’t we all just share our problems anyway?

My research suggests that part of the problem is our fear of being judged ‘mentally ill’.What if the person we confide in, instead of reassuring us, looks a bit shocked and suggests we see a doctor? This is a particular problem for the estimated one in ten of us who hear voices, and for those of us who experience paranoia. These experiences, sometimes called ‘psychosis’, were previously sometimes seen as symptoms of a brain disease called schizophrenia.

However despite billions spent on research, no underlying disease process has ever been found and many professionals now think the search is futile.

Increasingly, we are realising that whilst they can be very problematic for some people, such experiences are much more common than we think and do not necessarily mean you are mentally ill at all.

Indeed the whole idea of mental illness has been called into question.There may be more meaningful and useful ways to think about the various sorts of distress, confusion and difficulty that humans experience.

A few months ago my colleagues and I published a new version of our public information report ‘Understanding Psychosis and Schizophrenia: why people sometimes hear voices, believe things that others find strange, or appear out of touch with reality, and what can help’. The 24-strong author group included eminent clinical psychologists drawn from eight universities and six NHS trusts, together with people who had themselves experienced psychosis.

Our aim was to provide an accessible overview of the current state of knowledge, and our conclusions have profound implications both for the way we understand ‘mental illness’ and for the future of mental health services.

- The problems we think of as ‘psychosis’ – hearing voices, believing things that others find strange, or appearing out of touch with reality – can be understood in the same way as other psychological problems such as anxiety or shyness.

- Thinking of them as an illness is only one way of thinking about them, and not one that is shared by everyone or by all cultures.

- They are often partly or wholly a reaction to the things that can happen in our lives – for abuse, bullying, homelessness or racism.

- People who experience them are rarely violent. However, the unhelpful stereotypes can lead to people getting a poor deal from police and mental health services. If you are black you are particularly at risk: for example mental health services detain nearly four times as many black people as white people every year.

- No-one can tell for sure what has caused a particular person’s problems. The only way is to sit down with them and try and work it out together.

- Accordingly, no-one should insist that someone is mentally ill. Some people prefer to think of their problems as, for example, an aspect of their personality which sometimes gets them into trouble but which they would not want to be without.

- We need to invest much more in prevention by attending to the way we treat each other in our society. In particular, we need to address inequality, child abuse, neglect and bullying. Concentrating resources only on treating existing problems is like mopping the floor but ignoring the source of a leak.

Meanwhile, on Time to Talk Day, let’s talk about how we feel and what we experience without fear of being judged.

Image copyright: Giovanni Cassanese.

Dr Anne Cooke is a Principal Lecturer in the Department of Applied Psychology and Year 3 Director of the Doctoral Programme in Clinical Psychology at the Salomons Centre in Tunbridge Wells.

Expert comment

Expert comment Emma Grafton-Williams

Emma Grafton-Williams 2268

2268