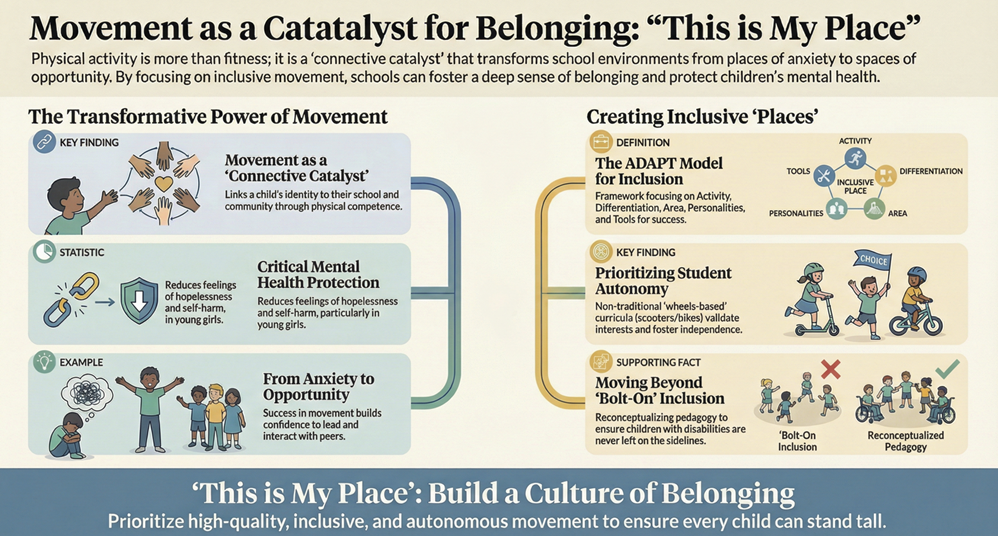

Professor Kristy Howells explains how her research shows that by offering high-quality, inclusive, and autonomous movement opportunities, we do more than boost health stats – we foster a school culture where every child, regardless of gender, ability, or background, can proudly say, ‘This is my place’.

This week was Children’s Mental Health Week 2026. This year’s theme, This is My Place, asks us to focus on the vital importance of belonging. It challenges us to create environments where children and young people feel safe, valued, and supported. While we often think of belonging in terms of social groups or physical classrooms, my research suggests that physical activity is a unique and powerful vehicle for fostering this sense of place. Movement allows children not just to occupy a space, but to own it, to understand it, and to feel safe within it.

In my work, Connective Catalyst of Movement, regarding “being, belonging, and becoming,” particularly within educational transitions, we have identified that a sense of belonging is fundamental to a young person’s ability to flourish. Physical Education (PE) and school sport should not be viewed merely as subjects for physical fitness, but as a connective catalyst that links the child to their school, their community, and their own identity. When a child feels competent in their body, the school environment changes from a place of anxiety to a place of opportunity.

We have seen this transformation vividly in longitudinal case studies. In Jonny’s Story, a 10-year-old boy with very low self-esteem and difficulties in forming relationships participated in a tailored physical activity intervention focusing on throwing skills. Over five months, the transformation was profound. He did not just get physically stronger; he developed the confidence to interact with peers and eventually became a house sports captain, speaking in school assemblies. For Jonny, the sports field went from being a space of exclusion to a place where he could say, ‘this is my place’.

The need for such mental health interventions is urgent for protection and resilience. Research highlights that school-based physical activity plays a critical role in protecting young people from mental illness. Movement helps remove distress and supports the development of a positive identity.

Crucially, the impact of physical activity is distinct across demographics. Evidence submitted to the UK Parliament as part of POSTnote 739 which explored children’s wellbeing in school, highlights that for girls, physical activity is especially valuable in combatting mild to moderate depressive symptoms and reducing feelings of hopelessness and self-harm. However, for this to work, the environment must be right. To ensure every child can say this is my place, our physical environments must be authentically inclusive. We must move beyond bolt-on inclusion strategies and reconceptualise our pedagogy. This is the core of the ADAPT model (Activity, Differentiation, Area, Personalities, Tools), which positions inclusion at the very heart of PE.

- Area: is the space accessible and welcoming? For children with visual impairments, for example, using tactile maps and sound sources allows them to navigate and claim the space as their own.

- Personalities: do we understand the emotional and social needs of the child?

- Tools: are we using equipment that enables success rather than highlighting failure?

When we apply models like ADAPT, we move from simply teaching sport to teaching children, ensuring that those with disabilities who are often the forgotten voices in sport are not left on the sidelines.

Finally, a sense of place requires autonomy. Children need to feel they have a choice in how they move. This is why I advocate for a broader curriculum that includes non-traditional activities, such as a wheels-based curriculum (scooters, skateboards, balance bikes). For many children, a scooter or a bike is their first taste of independence; bringing that into the school setting validates their interests and helps them become creative movers. By prioritising high-quality, inclusive, and autonomous movement opportunities, we do more than improve health statistics. We build a school culture where every child, regardless of gender, ability, or background, can stand tall and say, this is my place.

Kristy Howells is Professor of Children’s Health and Movement, in the School of Sciences, Psychology, Arts and Humanities, Computer Engineering, and Sports.

For more information on our research, or if you’re interested in undertaking research in this area, do get in touch with Professor Kristy Howells via email: kristy.howells@canterbury.ac.uk.

Expert comment

Expert comment Jeanette Earl

Jeanette Earl 310

310