Dr Keith McLay explains why Alex Salmond’s choice of quote on election night might not be a good omen – for him.

The General Election results threw up a number of surprises literally the length and breadth of the country. From Canterbury in the south east to my native north east of Scotland and the Gordon constituency, a Scottish National Party (SNP) stronghold which fell to the Conservatives.

The sitting SNP MP in Gordon was none other than Alex Salmond, a former Scottish First Minister, 2007-2014, and a parliamentarian who has represented the north east of Scotland for the Scottish Nationalists without interruption for 30 years, 20 of which were as leader of the SNP. A big Scottish political beast almost by definition.

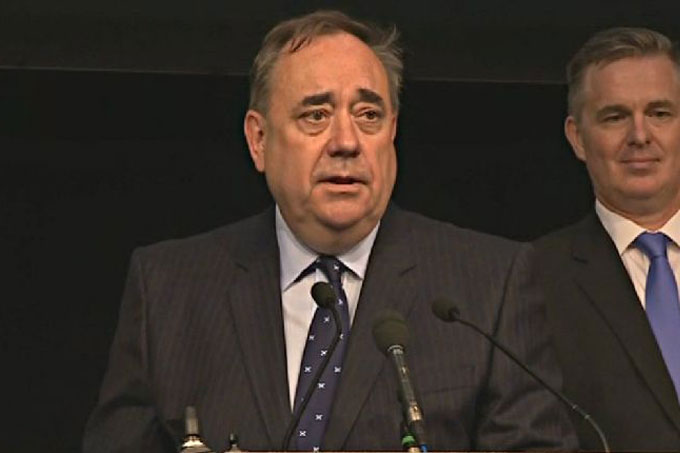

Consequently there was much interest when just a little after 4 am on 9 June Mr Salmond stepped up to the podium to deliver his concession speech.

It was in so many ways vintage Salmond. A little subdued to begin, the speech quickly became bullish in tone with attacks on political enemies and a defence of the SNP’s electoral performance and then, right at the end, defiance. Mr Salmond finished with the following quotation:

‘And tremble false Whigs, in the midst of your glee,

You have not seen the last of my bonnet and me’

Mr Salmond is a politician given to peppering his speeches and comments with references to Scottish history and Scottish literature and almost always his historical accuracy and resonance is on the mark. On this occasion, however, there must be some doubt in his choice of analogy.

He claimed the two lines were from a Jacobite song, which is true, but the tune was based on the poem Bonnie Dundee, written by Sir Walter Scott and published in 1825. It is a homage to a controversial figure in early modern Scottish history, the 17th century soldier and courtier, John Graham of Claverhouse, 1st Viscount Dundee, whose nickname gives the poem its title.

The poem Bonnie Dundee relates the story of Claverhouse’s defiance of the Scottish Convention of Estates (essentially the Parliament) during the popularly titled ‘Glorious Revolution’ of 1688.

In December 1688, the imminent arrival in London of the Protestant William of Orange had caused the Catholic King James VII & II, and William’s father-in-law, to flee to France. The Westminster Parliament, meeting temporarily as a Convention in January 1689, offered the throne to William and his wife Mary which prompted the Scottish Estates to convene in March to determine whether to make William a similar offer of the Scottish Crown.

Recently elevated by James to the Dundee Viscountcy, Claverhouse implored the Estates at its meeting in Edinburgh to remain faithful to James and the Stuart House. However, his representations fell flat and Claverhouse stormed out of the Convention, damming the Scottish nobles as deceitful and claiming that they had not heard the last of him; hence the two lines from Bonnie Dundee quoted by Mr Salmond.

On his departure, Claverhouse travelled north to Dundee where in April he raised the Jacobite standard in support of James and collected a force of some 2,000 men. In late July, Claverhouse led these troops into battle against the conspicuously larger Government army and gained a stunning victory but was himself fatally wounded. Obviously, the Estates did not hear personally from Claverhouse again while the 1689 Jacobite rebellion, which he had started, was subsequently extinguished within the year, and Scotland ultimately secured for King William.

So, armed with some knowledge of the history, it seemed uncharacteristic of Mr Salmond to invoke the memory, spirit and ‘bonnet’ of a man, John Graham of Claverhouse, 1st Viscount Dundee, of contested reputation and whose defiance to rejection proved hollow.

There were surely many other more effective examples with which Mr Salmond might have heralded his intention to return to frontline Scottish politics of which few doubt.

Dr Keith McLay is the Dean of the Faculty of Arts and Humanities, with a specialism in early modern military and naval history.

Expert comment

Expert comment Jeanette Earl

Jeanette Earl 2505

2505