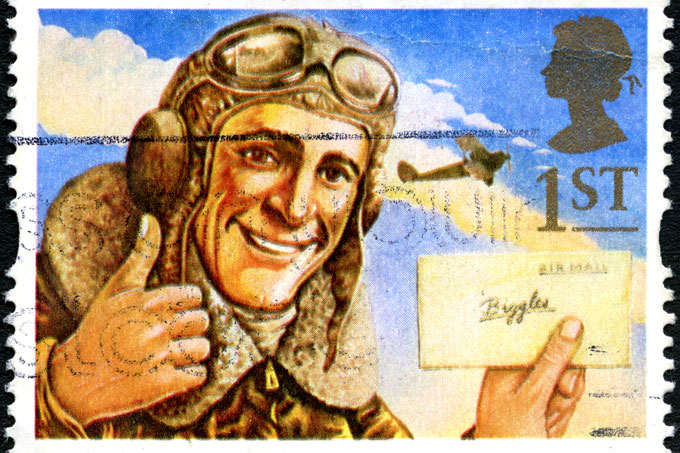

On the 50th anniversary of the first publication of Biggles books, Dr Michael Goodrum explores the character’s impact and legacy.

Biggles, and his creator Captain W. E. Johns, is a British publishing success story. The character, then a young James Bigglesworth, first appeared in 1932 in a series of adventures set in the First World War as a “counterblast to some of the war-flying nonsense that was being imported in the cheap papers” from American writers intent on elevating the role of their countrymen in the conflict.

Biggles went on to have dozens of high octane adventures around the globe over the next three and a half decades; on 21 June 1968, however, Biggles finally found the only thing that could stop him, when Captain W. E. Johns died mid-sentence, half way through writing what may well have been the last Biggles book anyway, Biggles Does Some Homework.

By that time, Biggles had appeared in nearly 100 books and attained the position of the ‘world’s most popular schoolboy hero’ according to the UNESCO Statistical Year Book of 1964.

The 1960s and beyond brought new threats into focus, though, most notably shifting attitudes around the political concepts seen by many as central to the character: Empire, violence, and martial masculinity.

These values are certainly there in Biggles books, but in complex ways. Biggles states that:

“While men are decent to me I try to be decent to them, regardless of race, colour, politics, creed or anything else… I’ve travelled a bit, and taking the world by and large, it’s my experience that with a few exceptions there’s nothing wrong with the people on it, if only there were left alone to live as they want to live.”

Issues certainly arise with regard to this statement, with Johns mounting implicit, perhaps even unconscious, defences of imperialism as well as explicit critiques of it, as when in 1960 Johns refers negatively to Empire as the “casual seizure of other people’s property.”

These complexities aside, it is clear from Biggles’ adventures that one thing he values, both in maintaining national interests and as an end in itself, is European collaboration. Biggles and his team work closely with the French police, represented by Marcel Brissac, and through their adventures forge links with like-minded representatives across the continent.

Biggles’ relationships with the Americans is rather more difficult, with upstart young Americans usually taking longer than Europeans to appreciate the advice and assistance Biggles has to offer. Even those who had formerly been opposed to Biggles, however, such as his long-standing nemesis Erich von Stalhein, are ultimately reconciled: Biggles rescues von Stalhein from the Soviets in 1958 and, in 1965, the two undertake a mission to Czechoslovakia to free Marie Janis, a woman with whom Biggles had fallen in love with nearly fifty years earlier during the First World War.

While built on his own personal relationships, Biggles routinely positions European cooperation as desirable and necessary. These values echo through other characters created by Johns, especially Worrals, his female pilot who appeared in stories from 1941-1950 and Gimlet, a commando who was in action from 1943-1954; all of Johns’ heroes were well versed in European languages and culture. While much else contained within these books is questionable, in this aspect Johns still has an important message for our time.

Dr Michael Goodrum is a Senior Lecturer in History, for the School of Humanities.

Expert comment

Expert comment Jeanette Earl

Jeanette Earl 2727

2727