Dr Mitch Goodrum, Senior Lecturer in Modern History, explores modern political views on integration and multiculturalism and how they mirror views from the early 20th century.

Much has been made in the press of the leaked Labour manifesto taking us back to the 1970s; from the other political perspective, similar sentiments have been lodged regarding Brexit and a return to an idealised 1950s. In UKIP’s election slogan of ‘integration, not multiculturalism’, we see a return to American rhetoric of the 1910s and 1920s, though there are clear echoes in President Trump’s current language on travel bans.

The division between these two ideas, integration and multiculturalism, suggests that nations are homogenous, a clearly definable entity clearly marked on a map. It is only through the existence of such a space that ‘integration’ could be advocated over ‘multiculturalism’. In short, it is a fundamental misunderstanding of the nature of nations and nationality.

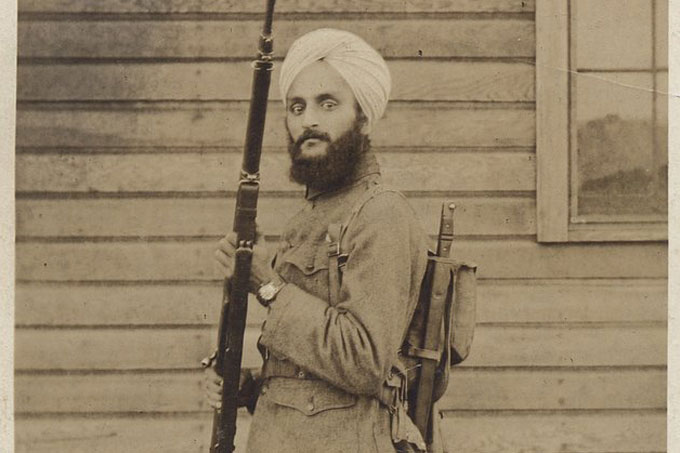

Similar ideas were in circulation in the USA during the 1910s and 1920s, where both Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson warned of the dangers of ‘hyphenated Americans’, which meant anyone who identified as, for example, Italian-American. Questions of citizenship, of national belonging – of integration, not multiculturalism – are most evident in the case of Bhagat Singh Thind, who in 1923 applied to become a naturalised citizen of the US but was turned down by the Supreme Court on the basis that “the children born in this country of Hindu parents would retain indefinitely the clear evidence of their ancestry.” As people of colour, they would be unable to fully integrate into what was conceived of as a white society. The ruling went on to state that “it is very far from our thought to suggest the slightest question of racial superiority or inferiority. What we suggest is merely racial difference, and it is of such character and extent that the great body of our people instinctively recognise it and reject the thought of assimilation.” Even though Bhagat Singh Thind conceived of himself as an American, and had enlisted in the US Army during the First World War, American elites could not conceive of him, or even his potential children who would be born on American soil, as Americans. Such nativist principles were subsequently enshrined in the 1924 Immigration Act, which was so draconian in its approach to who could enter the US and enjoy citizenship rights that Hitler cited it approvingly as an influence on his attempts to construct a homogenous, Aryan, Germany.

Although nations exist as territorial spaces, they are only given meaning through emotional and ideological investment. Benedict Anderson defines this as the creation of ‘imagined communities’, where abstract concepts of nationality are created and sustained through shared investment in cultural narratives of nationality. There is no reason that visual difference, what UKIP refers to as multiculturalism, must necessarily entail ideological difference, and therefore any less of an investment in notions of Britain, or being British. In fact, in rejecting notions of multiculturalism, UKIP rejects British history and its past status as the metropole of a global empire that necessitated the movement of goods, capital, and people in and out of Britain.

Regardless of how problematic this imperial history is, it still exists, and ‘Britishness’ is necessarily defined through an intimate relationship with our past, present, and future contact with other people and other cultures. My imagination and my idea of Britain is broad enough to incorporate and celebrate difference – to acknowledge that there are many ways of being British and that ultimately we are all hyphenated if we go back far enough.

Expert comment

Expert comment holly finch

holly finch 2623

2623