As Maidstone Borough Council requests a pardon for the Kent women executed for witchcraft in the 17th century, Dr Dave Hitchcock explains the background to the witchcraft trials, and the idea of restorative justice for all women killed for the crime of witchcraft.

Seven women were hung by the neck until dead on July 30th 1652 at Penenden Heath near Maidstone. It is quite possible that their neighbours and fellow village inhabitants were present at the time, as well as some of those who had accused the women of a spectacular crime we now popularly associate with the period: the crime of witchcraft.

Three of the women were set to receive a judicial reprieve which arrived too late, and the whole business formed one part of a larger ‘assize’ court session, which was where capital crimes and serious offenses were tried and adjudged during this period. Other women and some men were accused of witchcraft at that same session, but were not convicted.

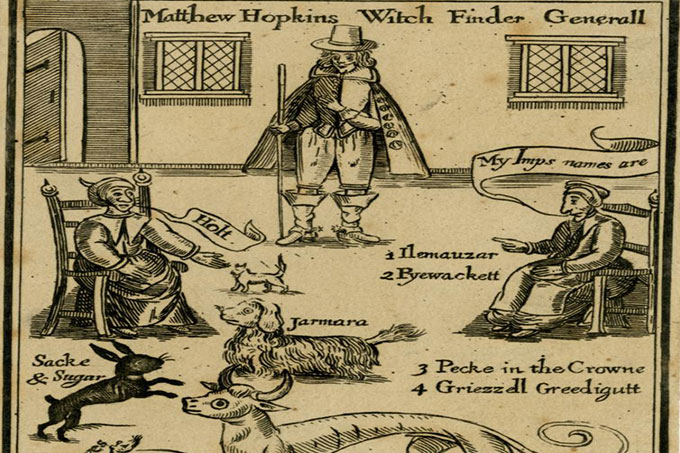

Historians of this period have examined witchcraft and magical belief in great detail, and the subject remains one which captures public attention. It is important to emphasise that the main characteristics which made these women vulnerable to accusation were their poverty, their marital status, and probably their age. Older, poorer, and often unmarried women were typically the targets of accusations and the criminal acts they were accused of often took on a gendered hue. An accused witch might have been suspected of child murder, or poisoning, or casting curses and evil eyes at their neighbours, or, as in this case, of accepting a pact with Satan in order to grant wishes.

In a letter to the Home Secretary today, county councillors for Maidstone have requested historical pardons for these six women. They intend to erect a memorial to remember injustices. Pardons that reach so deep into history are necessarily about how we conceive of right and wrong today, and how we try to align our systems of justice to those concepts. They would be worthy actions for no reasons other than those, though it is important to understand that for inhabitants of Kent in 1652, these accusations and executions were part of what “justice” looked like to them. What is just, and what standards of evidence need to be met to assure justice, are also things that change over time. Some women accused and eventually convicted of witchcraft likely committed very real and very secular crimes. Our modern sensibilities around justice tell us that no one should suffer capital punishment, whether an accused witch or an actual murderer.

Perhaps 500 or so accused witches were executed in this century in England. If we wish to pardon the Penenden six, why not pardon them all?

Dr Dave Hitchcock is a Reader in early modern British History.

Expert comment

Expert comment Jeanette Earl

Jeanette Earl 1520

1520