Was mental health care in the past as barbaric as we might think? John McGowan finds out about some innovators of the Victorian era.

What do we think of mental health treatments in the 19th century? My own mind conjures up shocking images of asylums, like the one where people were caged up in the film Amadeus, or the ‘Madhouse’ of Bedlam in Hogarth’s A Rake’s Progress (pictured above). Both were actually set in the 18th Century but it’s all folded into a general impression of imprisonment with some torture thrown in. (Bedlam, incidentally, is a corruption of the name of The St. Mary of Bethlehem Hospital in London which still exists, though we now know it as The Bethlem.)

However, my view of the 19th Century in particular may be somewhat selective. It was a time that also saw the beginning of psychotherapy (most prominently in the work of Sigmund Freud), and of what we might recognise as modern psychiatry (often traced back to Emil Kraepelin). Whatever you think of these developments, it’s clear that, in the 19th century, mental health care was part of the innovative sprit of the age.

The Bethlem Hospital of the time was not immune from a desire to change practices either, as I recently found out via the play Talk by Mark Wilson. Set in the Bethlem’s wing for the ‘criminally insane’ in the 1850s, the play tells the story of two doctors with different visions of how to reform the treatments of the time. Beauty, art and even (a radical idea) talking, were part of their new direction. I spoke recently to Mark about the play, mental health in the 1850s era, and how ideas from the Victoria era may influence us today.

DOTW: Your plays have ranged across a wide range of subject matter, from gangsters to Vivaldi. What drew you to the story you tell in Talk?

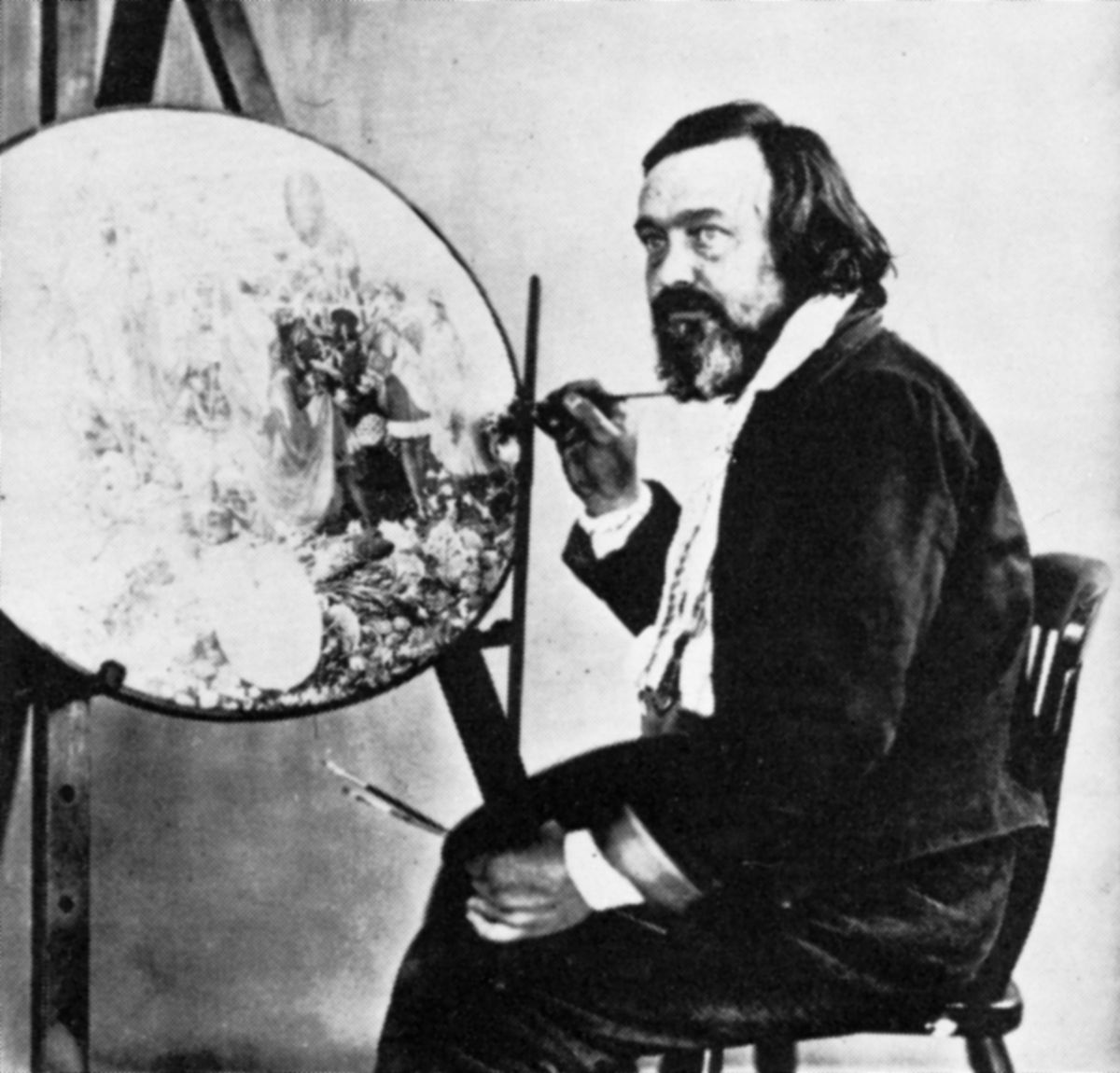

Mark Wilson: The idea for the play, originally presented to me as a Radio 4 commission, was not so much a story as a character: Richard Dadd, a Victorian artist who had murdered his father. My task was to find a story to put him in.

What struck me almost straight away was not so much the actions of the main character but the fact that, in what could be described as a brutal and unforgiving age, he had not been hanged for the crime. This suggested the presence of, at least to a degree, an enlightened understanding of the ‘criminally insane’ and, if that was the case, the high probability that a different, and less compassionate, understanding existed too. It also struck me that this same tension between compassion and something more punitive continues within society up to the present day.

The research very quickly bore this out. The treatments prescribed in cases of mental illness in the 1850s appear medieval in their barbarity. The fact that they seem to have been administered with a strong sense of belief in their positive contribution towards an inmate’s well-being only make them more so. At the same time, figures such as Charles Hood, the Chief Superintendent Physician at The Bethlem (where Dadd was initially an inmate), worked to initiate a more benign regime based upon the restorative effects of exposure to art and music. The story would be a conflict of ideas, with Richard Dadd as its unwitting focus.

Further themes that emerged were the opportunity provided by a mental illness for a husband to rid himself of his wife and, for adult children to hasten their inheritance by the removal of a ‘difficult’ parent. Thus I created the character of Emily Clayton, a poet, who would promote the idea of a link between our past experience and its impact upon our current behaviour. She also captures something about the sexism of the age, describing The Bethlem as being, ‘part of a system in which a man can be incarcerated for losing his mind, whilst a woman can suffer the same fate for daring to demonstrate that she has one.’

While I realise that the play is not necessarily supposed to be a historical document, you’ve indicated it involved a fair amount of research into the history of psychiatric hospitals. Can you say more about that?

The research revealed the 1850s as being a time that saw a considerable number of alternative experiments – some of them quite bizarre – in the treatment of mental illness. This was the case in this country and abroad; one thinks of the innovative work of Jean-Martin Charcot at the Salpêtrière in Paris. I was immediately struck by the enlightened thinking of Charles Hood and his belief in the restorative power of the arts and of treating people as cultured beings deserving of respect. Contrast that with the more traditional strapping inmates to bedframes or plunging them into baths of freezing water. What I found extraordinary was that the belief systems that promoted these very different types of approaches existed at the same time. It was a profound experience to research this conflict and tell the story of the the very different results each set of treatments produced.

The research also suggested a tendency on both sides towards doubt in their own methodology. I wanted to present all of the characters as essentially fragile and to deny the audience any sense of certainty as to the play’s outcome. I imagine Hood, for example, as a man not without his moments of despair. One can read his case notes on Richard Dadd written in his own hand in large leather-bound ledgers stored at Bethlem’s current location. The early notes are detailed and refer to small signs of improvement in Dadd’s condition. However, as the months and years go by, we read on page after page the simple statement: ‘No change.’ I could almost hear him sigh as he blotted the page and closed the book.

The play is set in a ward for the ‘criminally’ insane. Were there other sorts of wards too, or were people who were mad simply assumed to be, if not always bad, then at least dangerous?

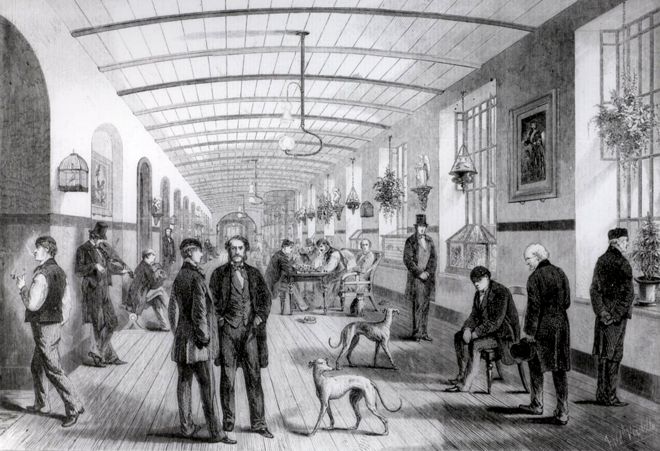

The criminally insane – those whose acts defined them as a potential risk to others – were kept apart from other inmates. However, their treatment under Hood’s regime was similar to that of the other patients. They enjoyed art on the walls of their parts of the hospital, the installation of aviaries – so convinced was Hood of the restorative power of birdsong – and participation in evenings of dancing and music.

Do you feel that Dadd’s difficulties, which would probably be classed as schizophrenia or psychosis in the present day, were related to his work (which often featured mystical and magical themes)?

Dadd’s artistic talents were evident well before the onset of his illness. He was made a member of the Royal Academy and was appointed artist in residence on Sir Thomas Phillips’ tour of the Middle East during which his use of hashish has been seen as one possible cause of his mental illness. I don’t detect an obvious shift in his working style as his illness became more pronounced. Perhaps his best-known piece, The Fairy Feller’s Masterstroke (on show at Tate Britain) is significant for its extraordinary detail. The build-up of layers of paint brings it to the point where it almost appears to be a piece in 3D. However, when set alongside his work painted at roughly the same time it appears quite unique as opposed to being part of a discernable trend. Perhaps the result of a particular episode? His series entitled ‘The Passions’ is highly representational. One of its pieces showing a man cowering in chains seems quite clearly to be a perfectly sane expression of his own situation.

You’ve said Charles Hood was something of an innovator at the time. What would we would think of his views and practices now, I wonder?

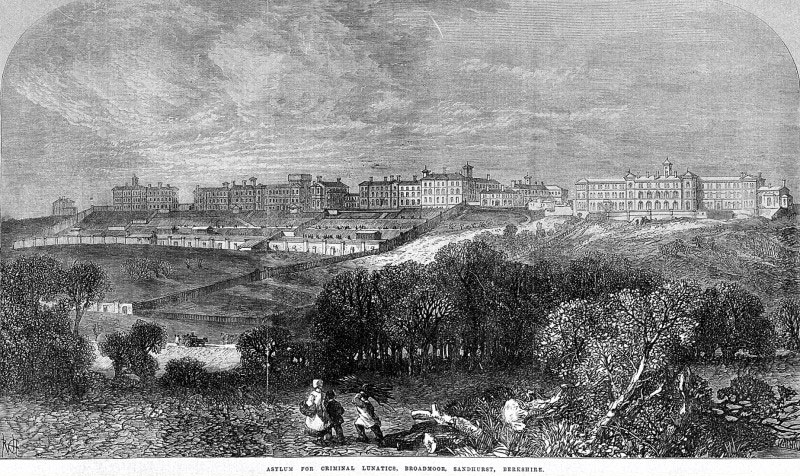

The fact that the Government-appointed Lunacy Commission was willing to support Hood’s approach to the point of funding the creation of a new hospital complex with him at its head (at Broadmoor in Berkshire) is evidence of a considerable shift in both attitude and expectation. I can only think that, as the period saw huge advances in science and in the treatment of physical illnesses, the time was right for those advocating new approaches in all sorts of areas. This was a wave that Charles Hood was able to ride.

As for how we would view his approach now, we would surely want ‘evidence of impact’. In itself, we know that playing music to people with mental health problems will probably not bring about a cure. However, in an age in which it has been suggested to patients suffering depression that they might benefit from watching the James Stewart film, ‘It’s a Wonderful Life’, Hood’s approach does perhaps have a place.

The other doctor in the play, George Haydon, is in many ways positioned as a forerunner of the kind of psychotherapies we might recognise in the present day. As well as being slightly ashamed I’d never heard of him, it left me wondering why he seems to have been forgotten?

I took some poetic license with George Haydon. He was in fact the Hospital Steward at Bethlem, not a doctor. Had I left him in that role he would have simply been made to stop his ‘talking with patients’ by Charles Hood, his obvious superior.

In order to create the possibility of tension between them and thus broaden the play’s emotional scope, I had to adjust their relative hierarchical positions. That’s why I ‘promoted’ him. I also wanted to add the dynamic of an increasingly strained friendship and professional partnership of these two young Turks challenging the established order as they gradually go their separate ways. It would have been rather two dimensional to have had Hood and Haydon firmly of the same mind from beginning to end. Indeed it would have removed the need for Haydon as a presence within the play’s structure.

After his retirement from The Bethlem in 1889, the real George Haydon was often recalled with fondness both by staff and inmates, many of them making reference to his ‘talking with patients.’ He died in 1891. Nine years later, Sigmund Freud published ‘The Interpretation of Dreams’ and the importance of the therapeutic encounter between doctor and patient became established.

Talk is being performed at the Marlowe Studio in Canterbury from 27th to 29th July 2017. You can find further details here.

The Bethlem Museum of the Mind has a blog and a Twitter feed where you can read more about the history of the hospital and look at images from their photo collection.

Discursive of Tunbridge Wells

Discursive of Tunbridge Wells John McGowan

John McGowan 6325

6325

This is very descriptive. I would like to watch the play and the film.

So descriptive it gives the chills……

Chills indeed. In editing this piece I found many picture of some of the devices used in treatment at the time. More like instruments of torture than anything with a remotely healing purpose. Still, it’s interesting to find out that that isn’t the entire story of 19th Century mental health care.