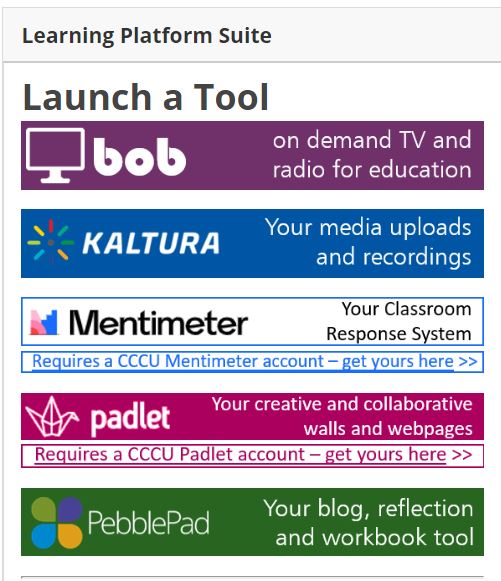

Last week in her blog post, Kate Davies looked at some of the resources available to support blended learning. This week, we are going to look at some of the go-to services that can help you create a truly blended learning experience in Blackboard.

Checking your reading lists

Well, hang on a minute, what has that got to do with the library? Well, quite a lot really. Apart from the obvious fact that we buy the books and put them on the shelves, we also meet a lot of students clutching reading lists and scratching their heads in confusion. We probably think about reading lists in the library more than you think. So much so, that we are running a pilot to introduce reading list software in 2021.

So why do we care so much?

In research conducted at the University of Northampton, students are more likely to go running to the library for “essential” reading rather than “useful” or “indicative” reading (which was seen as a “non-word”) (Siddall & Rose, 2014, 61) Core titles also get the thumbs up. Have you ever asked your students to evaluate their reading lists or asked them if they can improve them? (A pre-dissertation activity to improve the information-seeking skills of your students perhaps?) As we move towards reading list software wouldn’t it be great to get those reading lists into ship-shape order? But, also to put in place some mechanisms to make them living and breathing documents. How many reading lists are co-created by academics and students in partnership? You might even use this as an opportunity to discuss refreshing the curriculum or decolonising the content with your students.

At Northampton, it was also discovered that students dislike inaccurate references and cramped type-face, but did like “clear layout, annotations and student recommendations” (Siddall and Rose, 2014, 60). How often do you respectfully nod when you find an excellent piece of research cited in an assignment, that you hadn’t read yourself? Wouldn’t it be great if the students told you how they found it and why they chose it? And then told the upcoming year group? According to Devine (2017) the reading list “shouldn’t just be a list” although Devine does like the mega-list and is happy to defend it (Taylor, 2019). So, let’s look at ways that we can reinvent it and make it a pedagogical tool to improve students’ engagement with texts.

Padlet is a great online collaborative tool for creating and sharing reading lists. (It is one of the tools on offer on your Blackboards) You can create a flipped learning activity in which students rank reading, giving it a readability score and assessing its relevance to their learning (there are options to give comments, post reactions or grade answers). Not only will it improve their critical reading and thinking skills, but it will allow them to feel they are moulding their own curriculum. Let your students own their reading; and spend time selecting, reviewing or rejecting it. Speed date a few titles. Defend your choices.

And find out why students read some things and not others. Students get very frustrated if recommended texts are inaccessible (Martin and Stokes, 2006) but may feel too uncomfortable to raise this with their tutors. It’s not just a question of not finding them in the library, but if linguistically and intellectually the content feels too challenging, maybe the arguments within them need deconstructing in more manageable chunks. Find out what it is that the students don’t like? How often do we drill down into the NSS question: “The library resources (e.g. books, online services and learning spaces) have supported my learning well” to find out what exactly our students think?

At the University of Worcester, on one of the business modules, the reading is labelled “Essential”, “Extra” and “Challenging”. This enables students to “engage with the reading at different levels depending on their interest, aims and, quite probably, time available” (Taylor, 2019). By giving reading labels you are inviting discussion. But is this pre-judging material based on our own knowledge set? Who decides that it’s challenging?

Example activity of a synchronous activity that focuses on problem-solving, discussion and debate:

Give students three journal articles and a checklist of criteria relating to their needs such as relevance to an essay topic, or the validity of data – ask them to think about the evidence, and invite them to put their least favourite (based on critical analysis) in room 101. This can be a flipped learning activity or involve using breakout groups in Blackboard Collaborate, with groups returning to the main room for a final vote. Or if publicly battling the merits of an article feels too much, you could encourage students to reflect on their reading choices using PebblePad (a blog, reflection and workbook tool).

And, act on the evidence. Don’t leave reading to fester on an ever-growing list if it is no longer fit for purpose, as students hate “endless lists” (Siddall & Rose, 2014). If you would like more support in running a reading list workshop with your students or for a member of the Learning Skills Team to develop a critical reading activity with your students, please get in touch.

Requesting chapters for Blackboards

One of the services, that really shouldn’t be overlooked is the scanning service. If the library has one copy of a text and you have twenty students on your course and you are recommending only one chapter, it’s perfect. The library can scan a copy of the chapter for you, which can be neatly embedded in your Blackboard. No messy login and the chapter is only one click away for your students. A lot easier than going to the library. Not only this, it is legal, because the library confirms the copyright with the Copyright Licencing Agency, whereas photocopying the chapter and adding to the Blackboard yourself is not. Copyright laws are designed to protect the rights of authors (and as researchers and writers yourselves, I guess you wouldn’t want to lose out on your royalty payments either).

“The scanning system is invaluable, and will be even more so this academic year as we move to increased blended learning. I use the system extensively to share extracts of key texts and further reading with students on BA and MA programmes. Scanned documents make it possible to share resources that students might otherwise find difficult to access; it is ideal for highlighting a passage from a text for critical discussion, close reading or as a follow up resource. I’ve found that students often seek out the whole text as a result of reading a snippet in a scan; hosting the scanned text on Blackboard means it can be returned to at any time, supporting assignment preparation” – Sonia Overall – MA Creative Writing Lead, Senior Lecturer, Creative and Professional Writing

There are plenty of people, videos and guides to support you with the scanning service. Click on the links below to find out more.

Scanning Service (via StaffNET only)

Adding a scanned file to your Blackboard (via StaffNET only)

Obtaining E-books

This one probably sounds fairly obvious in a flipped learning environment but providing e-books ensures that reading is available to all online. Not only does it offer parity of experience, but it means more students can access the resource if the print copy is currently on loan. In a survey of foundation degree student reading in 2018, it was discovered that accesses to the recommended e-book study skills titles increased significantly in the lead up to assessment (Crowther, 2019)

However, the library’s role in purchasing e-books doesn’t just stop there. We really do worry about the value and the accessibility of the content for the students. The Learning and Research Librarians create support material about locating and using e-books, as well as coming into classes (online ones too! – we know our way around Blackboard Collaborate) to demonstrate the resources. If you would like a video tailored to your subject, do get in touch. We have plenty of “pre-recorded core knowledge acquisition activities” (LTE, 2020).

The library will also investigate alternate format material for students who struggle with e-book readers. You can contact the user experience team to find out more. We know that not everyone likes to read online, so we try to think of solutions, for example, our database guides have accessibility guidelines and Library Search has an accessibility view. You can also draw on the support of IT colleagues who produce a list of productivity tools to ensure parity of experience.

And just as you “encourage, sustain and monitor student engagement” (yes, I’ve read the Blended Learning Practices guidelines) we think about engagement with the texts too. How does Generation Y navigate e-books – do they know about footnotes, endnotes, bibliographies and index pages, if they are more used to school online learning platforms, web pages and hyperlinks? How can we make them academic readers as well as writers? Why not find out about some of the critical reading support available via the Student Support Blackboard or get in touch.

We also keep quantitative data on e-book use too and if students don’t use them, we want to know why (we agonise about a lot in the library). But if you’d like to know more about whether a title is accessed, how long it is looked at, there are all sorts of analytics and fluid data that can be explored.

Copyrights (and wrongs)

Finally, what about copyright and attribution in the age of copy and paste? Do your students know it’s not appropriate to patchwork ideas together without acknowledging their sources and engaging in critical debate with them. Do they know about creative commons licenses and the use of online images? According to the government, Online Copyright Infringement Tracker (2018) an estimated 15% of UK internet users aged 12+ “consumed at least one item of online content illegally in the past three months” and 44% explained the reason for their infringement as “it is free”.

To argue that “It’s alright because their assignments are behind a VLE”, is not an excuse, as we have to ensure our students understand how to use online content and take good practice into their future workplaces. If you would like a workshop on the ethical use of academic material, we can run sessions on copyright and how to avoid plagiarism. Contact your Learning Skills Team to find out more.

Example of a copyright activity:

Ask your students to find out more about Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code and investigate Michael Baigent and Richard Leigh claim that Brown “appropriated the architecture” of their book, The Holy Blood And The Holy Grail, published in 1982 by the same publishers. Or listen to Matt Cardle’s ‘Amazing’ and compare it to Ed Sheeran’s ‘Photograph’ and discuss the copyright infringement claim. Ask your students how they would feel if a piece of their creative work was used by another and discuss essay mills. Create an online space for debate such as an online discussion board and use Mentimeter (available via Blackboard) or a Blackboard Collaborate poll to take votes.

Or if you want to check out a question on copyright, try our copyright helper tool.

Bibliography

Crowther, M. (2019) ‘Walking the path of desire: evaluating a blended learning approach to develop study skills in a multi-disciplinary group’, Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education: Special Edition: Digital Technologies. Available at: https://journal.aldinhe.ac.uk/index.php/jldhe/article/view/475 (Accessed: 1 July 2020).

Devine, L. (2017) Reading lists: justifying the benefits for both students and lecturers. Available at: https://support.talis.com/hc/en-us/articles/115004062029-Reading-lists-justifying-the-benefits-for-both-students-and-lecturers-webinar- (Accessed: 1 July 2020).

Intellectual Property Office (2018) Online Copyright Infringement Tracker Latest wave of research (March 2018) Overview and key findings. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/729184/oci-tracker.pdf (Accessed 1 July 2020)

Learning and Teaching Enhancement (2020) Blended learning practices for September 2020. Canterbury: Canterbury Christ Church University

Martin, L. and Stokes, P. (2006) ‘Reading lists under the spotlight: Cinderella or superstar?’, SCONUL Focus 37 (Spring), pp. 33-36.

Siddall, G. and Rose, H. (2014) ‘Reading lists – time for a reality check? An investigation into the use of reading lists as a pedagogical tool to support the development of information skills amongst Foundation Degree students,’ Library and Information Research 38(11), pp. 52-73.

Taylor, A. (2019) ‘Engaging academic staff with reading lists’, Journal of Information Literacy 13(2), pp. 222-234. Available at: <https://ojs.lboro.ac.uk/JIL/article/view/PRJ-V13-I2-3> (Accessed: 01 July 2020).

Featured Image: by Luisella Planeta Leoni from Pixabay

Library

Library Michelle Crowther

Michelle Crowther 1254

1254