The murder of Black British teenager Stephen Lawrence on 22nd April 1993, and the revelations that followed in the wake of this horrific event of a bungled investigation by an institutionally racist Metropolitan Police Service, are ingrained in the British public consciousness. The Lawrence family have endured so much but through their vocal campaign for justice and reform they have brought about vital change in policing and the criminal justice system. The official Black History Month 2019 campaign theme is the celebration of Black women and their invaluable contributions to British society, particularly in the years since the Windrush generation arrived and settled in the UK, and one woman whose impact and achievements have been incredibly admirable is Stephen’s mother, Doreen Lawrence. She has worked tirelessly to advance community relations and human rights, and has become one of the most influential people in the UK.

A murder that shocked the nation

Born Doreen Delceita Graham in 1952 and raised in Jamaica until the age of nine, Doreen Lawrence emigrated to England and settled in South East London. She and her husband Neville had three children, Stephen, Stuart, and Georgina, and at the time of Stephen’s murder Doreen Lawrence was working as a special educational needs teacher. Stephen was a talented track athlete who ran for a local athletics club, and he had ambitions to become an architect. He was waiting for a bus in Eltham on 22nd April 1993 when he was swarmed by a known local gang of men and fatally stabbed. The police handling of the murder case was flawed from the start, with leads not followed correctly and arrests not made until a fortnight later. Astoundingly, Detective Superintendent Brian Weeden, who took over as lead of the investigation on its third day, would later announce that he had not known arrests could be made upon the basis of reasonable suspicion, a basic tenet of criminal law. The Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) decided that there was insufficient evidence to convict any of the five suspects the police had identified, and the two that had been charged with murder after being picked out of a line up had their charges dropped. Doreen and Neville Lawrence did not rest in their pursuit of justice for Stephen, launching a private prosecution against the five men the following year. This proved unsuccessful, with the charges being dropped against two by the CPS, again for lack of evidence, and the other three being acquitted. The Lawrences, however, did not stop lobbying for the Met to face repercussions for their failure to adhere to protocol and the unprofessional way in which they had conducted their investigation.

A barrel of rotten apples

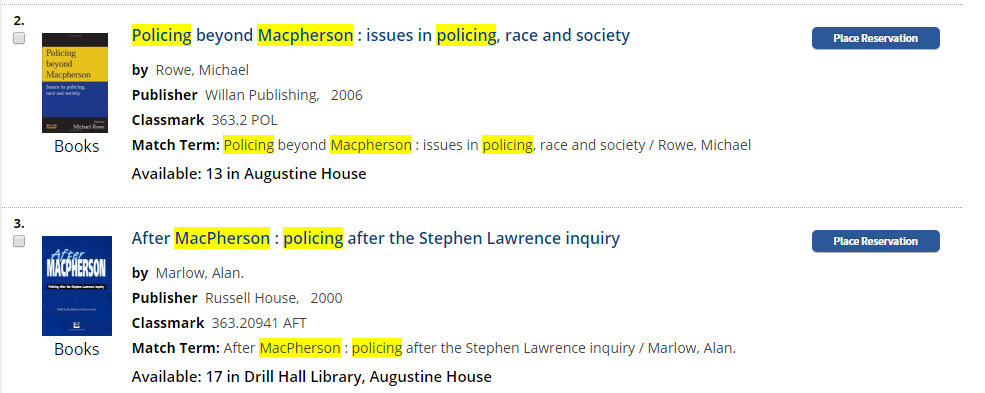

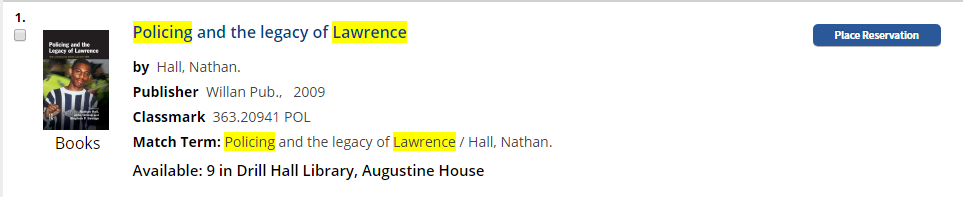

In 1997 an inquest into Stephen Lawrence’s death was held and despite the five suspects’ refusal to answer any questions, the coroner’s jury delivered a verdict of ‘unlawful killing in a completely unprovoked racist attack by five white youths’, a judgement which went beyond the bounds of their instructions. Doreen Lawrence condemned the Met and its racism, and described some parts of the inquest as a ‘circus’. Later that year, the Home Secretary Jack Straw ordered a public inquiry into the Met’s handling of the case. Conducted by Sir William Macpherson, it came to be known as the Macpherson Report and it changed the face of modern policing. As part of her statement to the inquiry, Doreen Lawrence said, “No black person can ever trust the police”, a damning indictment of a service not fit to protect the citizens under its charge. The Macpherson Report was published in 1999 and made a total of 70 recommendations for reform covering both policing and the criminal justice system. In addition to finding the Met institutionally racist, the report crucially proposed abolishing the double jeopardy rule that meant a person could not be tried more than once for the same offence, and blanket criminalisation of racist statements even if made in private. The impacts of Stephen Lawrence’s murder, the report made by Macpherson, and the public outcry provoked by the murder and subsequent actions of the police, can be seen in the library’s policing section, for example the titles below:

Still she rose

The case of Stephen Lawrence’s murder and his mother’s unrelenting campaigning have been covered intensely across a huge number of news outlets. Using the database Lexis Library Newspapers UK, accessed through LibrarySearch, you can search a vast archive of publications and read contemporary reports on the investigation and its outcomes. Doreen Lawrence showed incredible fortitude throughout all of these events and never stopped raising her voice to demand justice, for Stephen and for other victims of racist crime. In fact, in 1998 she set up the Stephen Lawrence Charitable Trust, which does vital work to support young people in their schools and communities, helping them to overcome disadvantage and discrimination. The trust also works to foster greater inclusivity and diversity in business, particularly management, and campaigns for fairness and social justice, ensuring that the lessons learnt in the wake of Stephen’s murder are remembered and acted upon. In 2003, in recognition of her outstanding work and commitment to improve the lives of young people from disadvantaged socioeconomic backgrounds and address systemic discrimination, Doreen Lawrence was awarded the OBE for services to community relations.

Justice for Stephen

A cold case review of Stephen Lawrence’s murder was opened in 2006 which involved a full re-examination of forensic evidence. Stephen’s hairs, a microscopic stain of his blood, and fibres from his clothing were found on clothing belonging to two of the suspects and this evidence was used to secure a murder conviction against them in 2012, with the previous acquittal of one of the men being quashed. They received life sentences. Stephen was attacked by more than two men that night in April 1993 however and Doreen Lawrence has stated that while the prosecution of Gary Dobson and David Norris gives her some peace, the others, Neil and Jamie Acourt, and Luke Knight, remaining free and unpunished means “I do not think I’ll be able to rest until they are all brought to justice”. The case of Stephen Lawrence was in the news again in 2013 following disclosure by a whistle blowing former undercover police officer who announced that he had been heavily encouraged by senior Met officers to conduct surveillance on and smear the Lawrence family in order to discredit their campaign. In response to these revelations, Doreen Lawrence stated, “Out of all the things I’ve found out over the years, this certainly has topped it. Nothing can justify the whole thing about trying to discredit the family and people around us”. Last year, stories of ‘spycops’ hit the news, with reports of a large number of people who had encountered undercover police officers gathering intelligence on them and their affiliated groups, with some even duped into long term relationships with said officers, or rather with their aliases. A public inquiry into undercover police activity was conducted and Doreen Lawrence was a core participant.

“education…the most precious gift”

In 2012 Doreen Lawrence was one of a select few to hold the Olympic flag during the opening ceremony of the games, and in the same year she received a lifetime achievement at the 14th annual Pride of Britain Awards. The following year Lawrence was elevated to the peerage as Baroness Lawrence of Clarendon. Clarendon is a parish in Jamaica and Lawrence’s honour is rare for being designated after a Commonwealth location outside of the UK. In addition to work within her own charitable trust, Lawrence is a patron of Stope Hate UK, and is both a board and council member of human rights organisation Liberty. De Montfort University in Leicester has opened the Stephen Lawrence Research Centre dedicated to research surrounding UK BAME communities’ history and culture, institutional racism, and the social psychology of racial violence, and Doreen Lawrence became chancellor of De Montfort in 2016. She has received honorary doctorates from a number of universities.

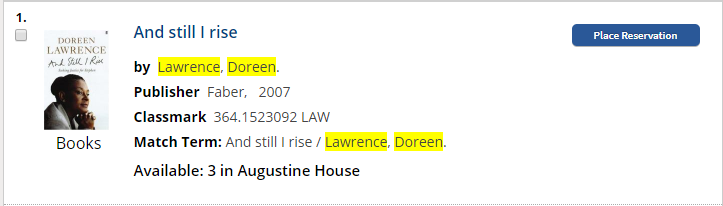

In the wake of tragedy, Doreen Lawrence has been a force for progression and change. The murder of her son should never have happened, and Lawrence should never have been put in a position where she had to fight not only for justice but also for recognition of a corrupt and incompetent police service that had failed her family and needed to be reformed. Institutional racism is insidious and tenacious and the battle against it within the Met is ongoing but there is no doubt that the Macpherson report has instigated vital change and Doreen Lawrence’s challenge of the racist system was a major catalyst. If you would like to read Lawrence’s story in her own words, her autobiographical book And Still I Rise can be found in the library’s collection:

Did you want to see me broken?

The title, taken from Maya Angelou’s brave and beautiful poem about thriving in the face of adversity, is incredibly apt for Lawrence’s story. In Angelou’s words:

“Out of the huts of history’s shame

I rise

Up from a past that’s rooted in pain

I rise”

Doreen Lawrence has truly risen. She soars.

Library

Library Emma Latham

Emma Latham 2424

2424