Yesterday, Dean Irwin, a postgraduate reseacher at CCCU, asked me if I had any tips for students who struggle to read on computers (even with assistive technology) and who don’t have access to a printer. I am not a specialist in this area, but in this blog I will attempt to share some tips for making reading library resources online a little easier.

Dean’s query really struck a chord with me as it’s a problem that I also suffer with, as anyone who has seen my desk piled high with papers would testify. When reading a journal article, I prefer to print it and highlight the salient points, then precis the key points with annotations in the margin before putting pen to paper and forming my own argument. I then file it away in a lever arch folder marked “Read”. I marvel at the paperless desks that surround me in the library office and wish that mine could be like that, but I’m not sure that it can.

“on average 10% of the population have dyslexia (to say nothing of other specific learning difficulties) and it can be particularly demoralising to assume that everybody can easily make the transition to an online learning environment“

Dean Irwin

Now, as our world has been turned upside down, I am trying to work and study with one small chrome book and no printer connection. So what advice would I give Dean?

Choose small things to read

That may sound a bit flippant, but seriously a journal article is much quicker and easier to absorb than a book. At anywhere from 2,000 – 15,000 words they condense a lot of ideas (sometimes quite niche) into a small space. You can read a guide to online journals here.

One of the main problems I encounter when looking for articles, is finding journal articles that are written in plain English. If I have to read the opening paragraph of an article three times and I still don’t understand it, then I leave it, read another article, build up more knowledge in the subject area and come back to the first article when I feel mentally stronger. It’s hard without my trusty highlighter to find the key points if they are dressed in complex terms. I use the Ctrl + F function on the key board to look for key terms in a web page or a PDF version of a journal article (see this You tube Video to find out more). Not ideal I know, as I may miss key arguments by skipping and skimming through the article rather than reading the full argument, but if I can get the gist of an article, I can come back to it when my concentration levels are better, the house is quieter or I can return to the land of printers and paper.

Look for well-structured articles

Many (non-humanities articles) have a clear structure with abstract, introduction, methodology, findings and conclusions) which make it slightly easier to navigate. Abstracts are a boon, as they are basically a summary of the article and allow the reader an opportunity to decide whether they need to read further.

For articles that don’t have this structure, my top tip would be to Ctrl + F for key words that express arguments or ideas. The Manchester Academic Phrase Bank is useful for writers, but also readers of journal articles. I write a list of keywords that are used to signal key findings such as identifies/ shows/ demonstrates/ emerged/ confirmed/ concludes/ proves/ illustrates and use Ctrl + F to help me find those significant arguments that perhaps my tired brain might miss if I tried to read a whole article in one sitting. Once I have found those words, I then read the sentence and if it doesn’t make sense in isolation, I go back to read the paragraph, and then the whole section. Once I’ve done this, going back to read the whole article sequentially is easier, as I understand its structure and what it is about to say. I am not suddenly overwhelmed with new concepts as I know when the sea-changes are about to happen.

Citations are your friend

Another tactic would be to look at the article’s bibliography for citations. You might find the articles on which the author has based their inaccessible and jaw-droppingly difficult article are more accessible and readable than theirs.

Alternatively you can find out about what others have said about the article by using Google Scholar and clicking on the Cited by. It may just be that some one else has read the article and written a more succinct, easy to read precis of the ideas that are contained within the original article. Admittedly it’s not taking you away from the screen, but its reducing the time you spend struggling to comprehend the academic language of the original article. Watch this YouTube video to find out more.

Use e-books that have structure

A kindle download is great, but all that percentage mullarkey drives me to distraction as I don’t get a real sense of how big the book really is. It’s alright for reading fiction on a long flight but for non-fiction it’s a faff (especially on my antiquated kindle).

On the plus side, there is the option to try before you buy, by downloading a preview chapter. This gives you a bite sized chunk of the book on a screen that you can read in bed without having to lump a power cable with you. However, don’t rely on one chapter to form an argument. Tutors smell a rat when everything comes from chapter one. Missing out on the conclusion, for example, is not a good idea. If chapter one is readable, it might be worth downloading the rest. (Note: always check the library catalogue to see if we have a freely downloadable copy of an e-book, a Google Preview or review of the book before purchasing anything online.)

The library e-books

The library e-books provide you with contents pages, hyperlinks between sections, search functionality and an easily searchable index. My concentration wanders if I have to read an e-book from start to finish, but if I can search it for key chapters and look for keywords I am much happier. I often wonder if I am a poor student because I don’t read academic books from cover to cover, but in some circumstances there is really only one or two chapters that are relevant (particularly in an edited collection).

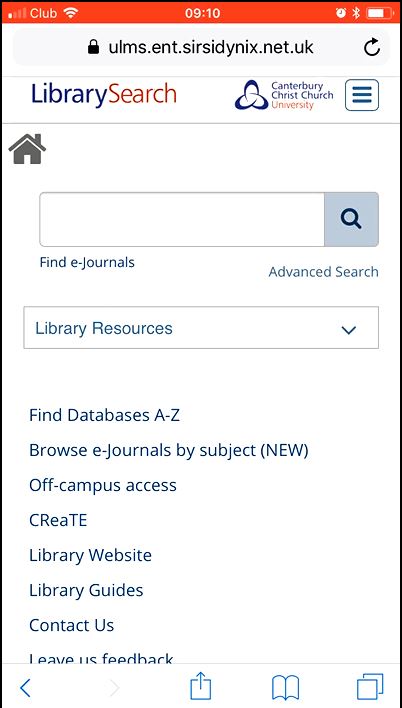

You can find e-books on Library Search, the library’s online catalogue and digital discovery tool. The video below explains how you can do this.

You can download an e-book or read online. If you have a flaky internet connection or limited data, you might wish to download, but bear in mind this is not a permanent download, as like all library books we are only loaning it to you. E-book downloads last one to two days. That doesn’t mean you can’t download them again at a later date and of course you can read online as often as you like (or not like, if like Dean and I you are cringing inside at the thought of online reading).

Navigating the online page

The structure of a print book is replicated in the library e-books. There is a navigation pane which allows you to skim the chapter headings and make strategic decisions about how much of the book you need to read. The value of providing hyperlinks is it allows you to read the book in a non-sequential way. The downside of adding hyperlinks to a print book is that print books are designed to be read sequentially and by hopping around the text, the thread of an argument can be lost. However, books have always been designed to be read in chunks anyway, so don’t let this put you off.

Approach reading an e-book in the same way as a print book:

- Read the chapter titles and make decisions about which key chapters you will read.

- Read the introduction, key chapters and conclusion to reach a better understanding of the key chapters in the wider context and go back and read any additional chapters which you feel will give you a broader and greater understanding of the topic.

- Browse the contents pages and index. e.g. If you are looking for Jews in France, the contents page does not tell you where you will find this, but the index will.

- Alternatively, use the Search function and look for “France”, “French”, “Paris”and “Capetian” and you get a clearer understanding of where you will find this information in the book and which chapters you should read. Note phrases can be searched in speech marks e.g. “French monarchy”

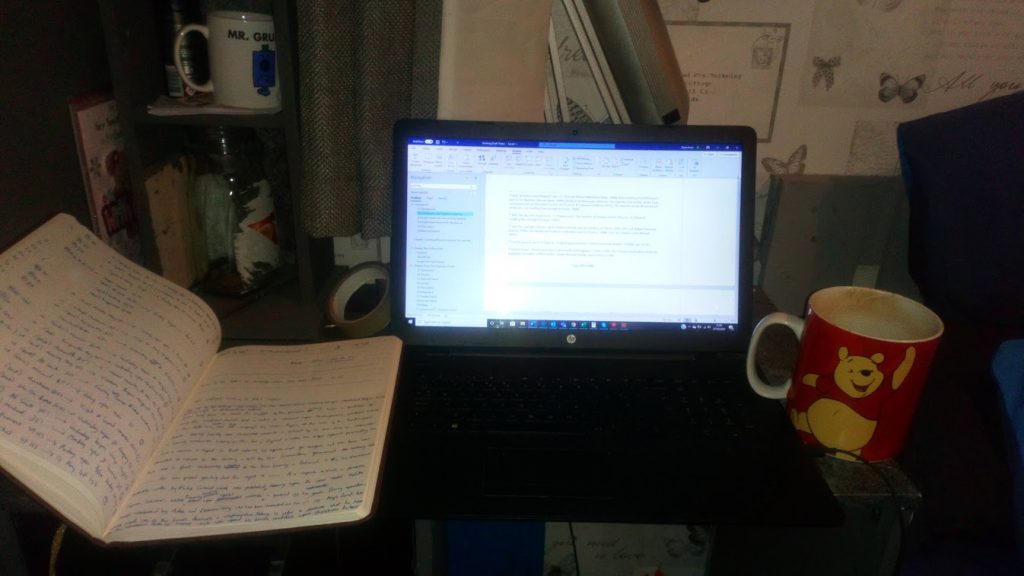

Keep notes

You can add notes to the e-book as you read it. This is useful as it gives you a pause between reading sentences or paragraphs to think about what it means and put it in your own words. Constant reading without pausing to take notes and reflect can lead to brain overload. If writing notes on a screen is just another chore to add to the many we do online today, then use pen and paper instead. A daydream can interrupt every paragraph if I don’t have a pen and paper in my hand, and writing as I read is essential to my overall understanding of a text. It’s the same as listening to a lecture or watching a video, unless I make notes I cannot retain the salient points but become seduced by the imagery or tangential thoughts (such as “Does she know that she says ‘erm’ before every sentence? or “I’ve got a pair of shoes like that”)

Things to follow up

Making a list of things to follow up as you are reading, helps you keep on track, particularly if you are tempted to do a bit of hyperlink hopping. Unfortunately the footnotes in some e-books are not hyperlinks, which is a poor design feature. If I could instantly see the source in a pop up window, I could jot down which footnotes I want to follow up. Instead I have to use the navigation pane on the left-hand side to go to the Notes section of the book (not to be confused with the Notes tab where you can add your own notes as you read). Going back to the page where the footnote originated though is a bit confusing, so it’s a good idea to jot down the page number before looking at the footnote and then type it in the page locator at the top to return to the page.

Managing your online space

Toggling between Library Search and journal articles which pop up can feel quite messy. In many journal articles the footnotes are hyperlinked and with too much clicking you can end up far away from your original source. It’s a bit like following a rabbit down a hole and wondering exactly where you started. Right-hand click to open a link in a new tab to ensure that you do not lose your original page and you can trace your way back along the tab bar at the top.

Reading on a phone

If balancing a notepad, pen and laptop on a cramped desk is difficult, you could do some of your research on your phone. I often work on both chrome book and phone so that I can have an extra browser. This tutorial explains how can you use your smartphone for research.

Reading e-books and journal articles on a phone can be tricky due to the size of the screen but most smart phones allow zooming using finger pinch actions.

Some also have accessibility settings which allow you to switch Speak Screen on. You can then swipe down with two fingers (next to each other, not spaced apart) and it will give you the option to hear the text.

If you are struggling with IT problems because your screen just isn’t like the ones at uni, get in touch with IT services. They are brilliant and have sorted out many issues for me. You can read their blog post about working from home to find out more

Getting more help

I can only give you a personal perspective on how I approach academic reading online. My colleagues in learning development know much more about critical reading and managing your studies than I do and you can book an online appointment with them via the Learning Skills Hub.

There are also many other services to help you with your studies in the university and this blog post signposts you to them. If you would like support with a specific learning difficulty, please contact the Student Support, Health and Wellbeing Team.

And Dean, if you’ve read my blog, I’m sorry that it’s so long. In our natural habitat I know we’d both print it. If any other students have any similar queries about accessing library resources online or any fantastic tips about how you manage your research we’d love to hear @ccculibrary

Library

Library Michelle Crowther

Michelle Crowther 679

679