It has been an interesting and busy week, and before I get to the William Somner conference on Saturday, I thought I would just mention that it was great to see the new Juxon Room at Eastbridge Hospital. They have certainly transformed a rather dark room into a light space that means the roof timbers are beautifully exposed to be admired at last. The other exciting feature is the glass floor panels that allow you to see the bridge timbers and the river below. See the photo below.

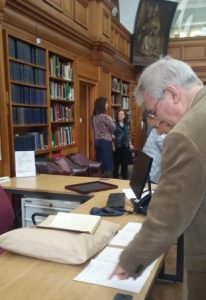

As a medievalist, I cannot pass over the workshop that the Centre ran this week as part of Women’s History Month – many thanks to Maxine Owen for organising the room and refreshments. Those attending were able to explore a range of sources showing the commercial activities of women in late 14th-century Canterbury, as well as the activities of their counterparts in early 15th-century Hythe. I have mentioned the Hythe local taxation records before, but it is worth reiterating just how informative these documents can be, albeit they are not the easiest of records to decipher.

Juxon Room – exposed timbers and the River Stour

In contrast, those for Canterbury look much easier to deal with, and, as well as poll tax and intrantes lists, I had provided several wills that had been proved in the burgmote. Thus, among the women I introduced people to was Alice Monde of St Mary de Castro parish who received a bequest of a messuage, seven shop and a garden with two ‘teynters’ from her husband John. As a result, she would have been able to rent out this valuable commercial property, although it is possible that she might have continued her late husband’s cloth-making business, the part finished cloth set to dry on the tenterhooks in her garden. This reference to the city’s cloth making in Richard II’s reign is not surprising because most of the single women documented in the 1381 poll tax were designated spinners, although what is interesting is that this is not reflected in the intrantes lists, but this seems to reflect different recording procedures because there were plenty of weavers in 1390s Canterbury and they would have needed the work of this army of spinners. If anyone is interested in Canterbury’s late medieval women as workers, you can find more in the Kent Archaeological Society’s journal, Archaeologia Cantania, 138 (2017), 179–99.

Discussing medieval women in the workplace

Returning to the 17th century – Archbishop Juxon was the first Restoration archbishop who, as well as being a major benefactor to Eastbridge, was responsible for the restoration of the great wooden doors at Christ Church gate and his coat of arms is on these gates as it is on Eastbridge – I’ll now turn to William Somner. Dr David Wright, who has written a substantial article on him that will be appearing in Archaeologia Cantiania in two parts, the first in 2019 and the second in 2020, had been involved, with Dr David Shaw, in the selecting of items for the exhibition organised by Cressida William at Canterbury Cathedral Archives and Library. The exhibition was enjoyed by the first 30 people who had bought tickets for the William Somner conference and comprised the day’s first session. To ensure the group enjoyed the exhibition and arrived at Old Sessions in time for coffee at 11.00, David Wright and Dr Diane Heath acted as marshals, while I and Mary-jane Pamphilon, who readers may remember often runs Reception at Centre events, welcomed the 20 people who were booked in for the lectures part of the day – many thanks David, Diane and Mary-jane. This meant that everyone managed to have refreshments before David Wright opened proceeding in the Michael Berry Lecture Theatre, introducing Somner and then chairing the ‘Somner and Canterbury’ session.

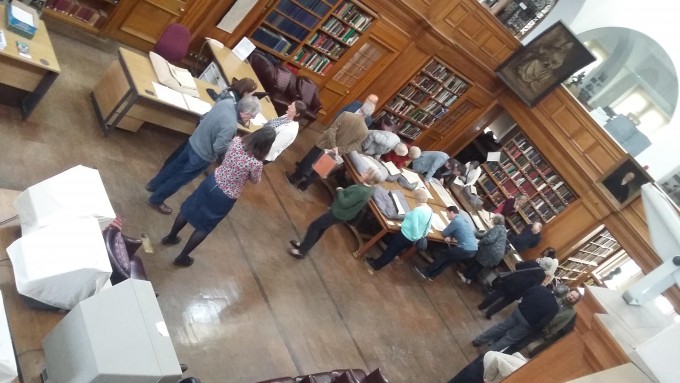

The Somner exhibition in the Canterbury Cathedral Archives & Library [photo Diane Heath]

Professor Jackie Eales spoke first. She drew on the 1641 poll tax records for Canterbury that provide valuable insights regarding the composition of the city’s population. These and other records demonstrate that the city was a vibrant place, the centre of a marketing hub (as it had always been), where the cloth industry had been revived by the presence of the Stanger communities, and many of these people maintained strong connections with continental Europe. There were also good lines of communication with London, whether by post or through trade and other links, while the presence of the ecclesiastical community at Canterbury Cathedral meant that clerics and lawyers were important members in the locality.

Jackie Eales discusses Somner’s Canterbury

Nevertheless, Canterbury was hardly immune from the rising political and religious tensions of the 2nd quarter of the 17th century, as exemplified by the pro-parliamentary petition of 1642 that includes 185 Canterbury signatures and over 4000 from Kent. As Jackie explained, this provides an excellent snapshot of the lines being drawn between the two sides. For example, the mayor and aldermen with men such as Richard Culmer aligned on one side as signatories, whereas most of the clergy and men such as William Somner and his father, another William, notably absent. Nor were these ‘battle lines’ confined to petitions, for the 1640s witnessed various acts of violence, such as the ‘Christmas Day’ riots, and destruction, including the demolition of the cathedral font, which must have polarised the city’s community still further.

For William Somner jnr these were dangerous times, and his short poems in praise of Charles I as a martyr, even though published anonymously shows his commitment to the royalist cause. Consequently, it was presumably with a great sense of relief, among other emotions, that he joined the crowds along the Dover road who welcomed back Charles II, and he remained in Restoration Canterbury until his death in 1669.

Having set the scene, the next speaker looked at one of Somner’s best known publications. Avril Leach is in the final stages of her doctorate at the University of Kent and she has become increasingly interested in his The Antiquities of Canterbury, especially the first edition. In her paper, she discussed Somner’s method respecting the layout of the book and how he used the rhetorical device of apparently walking with his reader around his beloved, ancient city. For it is this notion of Canterbury’s antiquity that is in many ways paramount as he employed documentary sources from the cathedral muniments with other works from fellow and earlier scholars, as well as the city itself to describe what was noteworthy about the city’s history, and especially that of the cathedral.

Avril Leach exploresThe Antiquities of Canterbury

Published in London in 1640 and dedicated to Archbishop Laud, Avril has located a 100 or so of these 1st editions, which she thinks may point to a print run of 200. As you might expect, some survive in Canterbury – at the Beaney (belonging to the city) and at the cathedral, including a copy annotated by Somner, but the spread is international. The 1660 edition is similarly widespread, including one at the Huntington Library in the USA that some think may be the copy Somner presented to Charles II. Indeed, Somner gave away a number of copies of both editions to patrons and benefactors, although others were bought albeit just how popular it was at the time is extremely difficult to gauge.

Both papers generated numerous questions and warm applause. In addition, there were people who wished to ask more when we broke for lunch. At this point, I want to thank CCCU Hospitality and Facilities for setting up the tables, providing refreshments and for opening the Old Sessions kiosk over the lunch break, conference participants and speakers greatly appreciated these facilities.

I chaired the first of the afternoon sessions where we heard first about Somner’s Anglo-Saxon/Latin/English Dictionary from Rachel Fletcher. Rachel is studying for her doctorate at the University of Glasgow where she is researching dictionaries of Old English from Somner’s time to the present, having first explored his dictionary for her Masters. She gave the audience some fascinating insights into how Somner (and contemporaries) apparently learnt how to translate Old English texts by employing Latin texts as a kind of crib sheet. This meant that the types of documents he used were often legal or ecclesiastical rather than literary, indeed he seems to have found the latter distasteful, so no Beowulf here! Yet, this was also a consequence of the times because the Reformation had witnessed the scattering of monastic libraries, even where these manuscripts had survived, thereby making his work far more difficult. Yes, some had gone to colleges at Oxford and Cambridge, the Parker Library at Corpus Christi College Cambridge having much from Christ Church Priory, but other manuscripts had gone to the Netherlands where the language was not that dissimilar to Old English.

Rachel highlights Somner’s attitude to Anglo-Saxon literature

As Rachel said, others had tried to produce such a dictionary before Somner, but it is most definitely to his credit that his is the first. Furthermore, his very careful work and considerable accuracy meant that his dictionary continued to be used well into the 18th century, and even when it was superseded, Bosworth’s new dictionary drew heavily on Somner’s earlier version. Thus, albeit sales were apparently slow in his own time, Somner’s legacy to the world of Old English studies is extremely important, and something that is often forgotten outside this small scholastic community.

Dr David Shaw followed Rachel, and he drew on his vast knowledge of the collections in Canterbury Cathedral Library to provide the audience with ideas about Somner’s own library, which his widow sold to the Dean & Chapter for £100 8s in 1669. Just how large this was is difficult to say because for price the D&C also acquired Somner’s bookcases. Moreover, William had already given some books to the Library before his death, the titles listed in the Benefactors’ Book. As a result, David has found about 100 of Somner’s printed books in the Library, often because Somner was in the habit of writing how much he had paid for a book followed by his initials. This is extremely interesting because it means David has been able to track Somner’s activities in the second-hand book trade, as well as providing the provenance of several volumes through numerous hands. For, just like his gifts to the D&C, Somner was the recipient of books, including gifts from his father, headmaster and patrons. David was keen to discuss these early influences on the young William, and these men were seemingly instrumental in his love of linguistics that meant he became proficient in a very wide range of languages, including Italian and medieval Welsh.

David Shaw assesses Somner’s book collection

Again, the session sparked lots of questions and comments, the speakers continuing to talk to people after the audience had shown their appreciation and had then headed out of the lecture theatre for further refreshments. Indeed, conversations about all the talks was evident from what I could hear throughout Old Sessions Foyer – a mark of a successful day!

David Wright chaired the final session when Professor Kenneth Fincham (University of Kent) gave a brilliant presentation on William Somners and William Laud because, as he said, both father and son need to be considered in order to understand William jnr’s relationship with Laud. As an expert on Laud, Kenneth was able to provide the audience with both the background to his elevation to Canterbury and to the complex political and religious changes that took place during the 1630s, especially as they involved and affected the Somners. William snr’s position as registrar of the Consistory Court of Canterbury until his death in 1638 meant that he was drawn into many of the controversies taking place during this decade involving, amongst others, the members of the Stranger churches, as well as criticism of the social habits of some of the clergy – the ‘demon drink’! For most of the time relations were good between Laud and his registrar, but he was castigated on one occasion for not supplying information to Laud on the diocesan clergy. Whether this had any bearing on the failure of William jnr to receive the position after his father’s death is unclear but perhaps unlikely. Rather he seems to have been seen as a safe pair of hands by Laud regarding the business of the court and as the chief notary public he deputised for Laud’s new registrar, as he had effectively done during the later years of his father’s tenure when William snr was getting increasingly infirm.

Kenneth Fincham examines Somner’s admiration for the cathedral’s new font

Nonetheless, William jnr did share Laud’s ideas about the value of scholarship, holding the archbishop in high regard. Moreover, a later biographer has suggested that William aided Laud to enhance the archbishop’s collection that was given to the Bodleian (and still named for Laud).

However, even with these shared ideas, Kenneth posed the question was William jnr a supporter in terms of the archbishop’s fervent desire to implement ‘the beauty of holiness’ and other controversial policies in the Anglican Church. Kenneth looked at this from several perspectives, concluding that probably Somner would have favoured a more middle way, but as a great admirer of the new font in the cathedral he was far more ‘going with the Laudian tide’ than against it. Furthermore, through his own scholarship respecting the medieval Church, he had considerable sympathy for the archbishop’s views.

Examining William Somner’s family tree [photo Diane Heath]

Kenneth’s lecture received enthusiastic applause and provoked numerous questions, including several about the cathedral font, something Kenneth greatly admires. To finish the day, David Wright thanked all the speakers for their great presentations, thanked the audience for their wide-ranging and well-informed questions and comments, and noted that any surplus from the day will go towards the Ian Coulson Memorial Postgraduate Award fund. Thus ended a fascinating day and it only remains to say that next month it is Tudors and Stuarts 2019: www.canterbury.ac.uk/tudors-stuarts and in May the Canterbury UNESCO conference: www.canterbury.ac.uk/unesco-conference – we at the Centre hope to see you there.

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 1992

1992