O for a beaker full of the warm South,

Full of the true, the blushful Hippocrene

John Keats, Ode to a Nightingale

The ‘warm South’ was Keats’ evocative phrase for the classical culture of the Mediterranean. I think it also encapsulates some of the special qualities of ‘The Gospels of St Augustine of Canterbury’ (CCCC 286). This is the famous book which Richard Gameson will discuss at the opening lecture of the Medieval Canterbury Weekend in April. It’s a talk everyone should flock to for the Gospels are truly amazing and Richard Gameson is the terrific expert on the early books of Canterbury. This post has the modest aim to provide some extra background for Professor Gameson’s talk – and so I’ve taken Mediterranean sunshine as my theme on this greyest of grey wintry days in Canterbury.

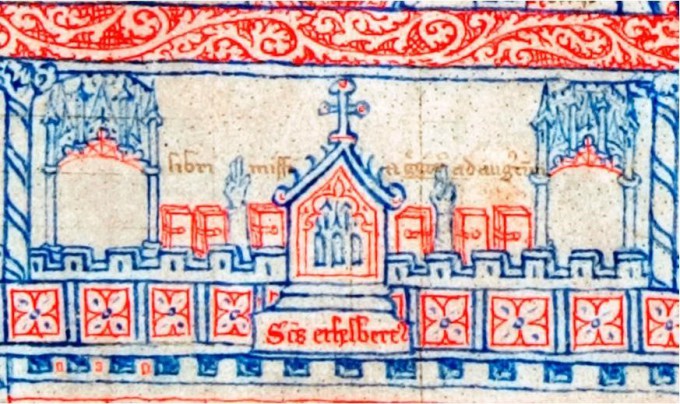

These Gospels are famous because they are old, far older than the cathedral. They date from the late sixth century and they may have been brought from Rome by St Augustine himself in 597 AD, or sent by Pope Gregory the Great to his missionary a few years after Augustine’s arrival in Kent. They were definitely in England in the late seventh century when headings lettered in the distinct Insular uncial script were added. These Gospels became one of the foundational book relics of St Augustine’s Abbey. There is an image of this and five other early books associated with Gregory the Great in Thomas Elmham’s Chronicle (now Cambridge, Trinity Hall Ms 1) which depicts the high altar where they formed objects of veneration for generations of monks. Two relics of saints’ arms are also visible making the sign of blessing.

What makes the Gospels so astounding – apart from their great age? Indubitably, it is the link the book has to Gregory the Great and St Augustine’s mission to Christianize the English but there are other reasons to celebrate the survival of this wonderful book. These Gospels are taken from St Jerome’s Vulgate text but as Anglo-Saxon and Carolingian expert Rosamond McKitterick has pointed out, they do not follow the normal punctuation. Instead the well-proportioned and spaced double columns are written ‘per cola et commata’ that is in phrases rather than sentences. This would make the Gospels much easier to read aloud – an important point if the book was intended as a gift for King Æthelberht, as McKitterick has suggested. Furthermore, this book also inspired comparison with other Gospels as notations in it confirm and thus it witnesses early attempts to establish scriptural textual authority. Furthermore it has tenth-century charters written in it between the books of Matthew and Mark (fol. 74v). This was always an important book.

Why do I associate these Gospels with Keats’s reference to the ‘warm South’? There is a world of time between these Gospels and the nineteenth-century poet. The’ Hippocrene’ red wine that Keats referred to in his Ode to a Nightingale meant the source of poetic imagination and the memory of ancient Italian grape-ripening sunshine. The phrase for me also conjures up ideas of the ‘blushful’ wine representing the blood of Christ in the Eucharist, from the Last Supper – as the Gospels bore witness. In another famous poem Ode to a Grecian Urn, Keats imagined a narrative which was inspired by the frieze on the ancient pottery recalling a time long since past yet permanently recorded by the urn, just as these Gospels recall not only the scenes from the New Testament but also the world of Late Antiquity which produced the manuscript book. These Gospels illuminate a period so distant yet immortalised by Bede’s description of the Gregorian mission to King Æthelberht. Keats’s odes celebrate that touch across time that ancient artefacts bring to the present.

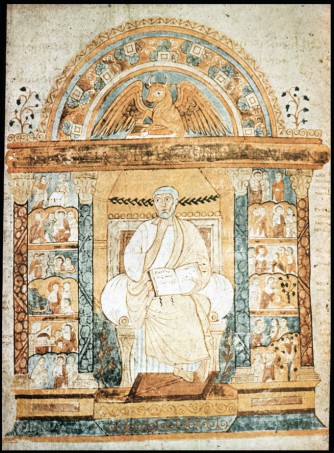

As the Parker Library blog points out, illustrations in books of this period are ‘extremely rare’ and this Gospels has two surviving full page miniatures. The one on which I concentrate here (fol. 129v) depicts a neatly-bearded white-haired St Luke holding open his book and wearing full and billowing Roman toga. Luke sits, musing with his right hand beneath his chin, in a chair with an enormous cushion in an amber room. A toast-coloured Roman architrave supported by four marble columns surmounted by the Evangelist’s symbol of the winged bull. Scenes from his Gospel decorate either side of Luke’s portrait, like two vertical strip cartoons. Yet it is the mellow tones of the illumination which imprint upon my memory the idea of warm and civilized Romanitas – the soft yellows and terracotta hues of Mediterranean sunsets and landscapes, the fading of the imperium and the hope of Christian rejuvenation. This miniature has a liminal quality about it. Luke sits within a Roman building yet his feet rest on a pavement with trees growing either side, as if he were inside the house, beneath the portico, and in the garden, while scenes from his Gospels run down between the columns. The pavement on which Lukes’ feet are delicately positioned resembles the closed Gospels which his symbol of the winged calf leans on above the architrave and within the arch at the top of the illustration. Both are chestnut brown with a diagonal stripe – implying the book is the gateway and threshold to a new life. So it was appropriate that these Gospels were present when Rome came to Canterbury again in 1982, when Pope John Paul II visited the Cathedral – these Gospels remain a gift.

I hope this post has whetted your appetite for Professor Gameson’s talk which will be a splendid start to the Medieval Canterbury Weekend – Friday 1st April, 19:00 – 20:30 Old Sessions House.

DEH

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Matthew Crockatt

Matthew Crockatt 925

925