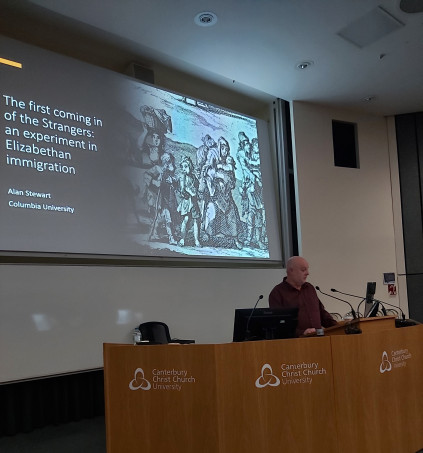

Last night (Tuesday 21 November) we were treated to a fascinating case study by Professor Alan Stewart concerning how the Strangers came to Sandwich in Elizabeth I’s reign. Consequently, this will be the main topic, albeit I want to flag up the Medieval Canterbury Weekend 2024 because tickets will be on sale from next month (December) and the Kent History Postgraduates have their regular catch-up meeting today.

Starting with the History Weekend, which will take place between Friday 26th and Sunday 28th April, I’m very excited to be welcoming back to Canterbury several of our great speakers, including Professor Mark Bailey who will take another aspect of life in post-Black Death England, Dr Janina Ramirez who considers the much greater place of women in history than is normally claimed and Dr David Rundle who will explore England’s contribution to the Italian Renaissance. We are also delighted to be bringing in new speakers to the Weekend, including Dr Anthony Gross who will examine how politics influenced the production of painted enamels from Limoges, the long-lived centre of this great craftsmanship, Dr Alexandra Lee who will offer insights into the ways people in medieval Italy sought to ward off the plague and Alfred Hawkins who will guide us through the Tower of London’s history as a royal palace.

As in previous year, the Medieval Canterbury Weekend will provide the popular guided tours, offering the chance to visit places not normally open to the public, fantastic medieval buildings and a bespoke exhibition of some of the treasures from the archives at Canterbury Cathedral. As those who have met Professor Paul Bennett will know, his knowledge about Canterbury’s history is vast, and for the History Weekend he will demonstrate how to read the development of a medieval church, in this case St Mildred’s, from its beginnings in the early 11th century to the building of the At Wood chantry 500 years later.

So please do look out for the programme and as in previous years it is a matter of selecting your own choices to chart your way through the Weekend. We have the bulk buy discount as usual and the CCCU Bookstall will be available with our lecturers’ books, as well as the opportunity to get them signed by our speakers. I am already recruiting student helpers as members of the MCW24 Welcome Team, so if you are a student at CCCU and are interested in being part of this great Weekend, do send an email to me at: sheila.sweetinburgh@canterbury.ac.uk

Now moving on to Professor Stewart’s lecture, he started by explaining how he as a Professor of English and Comparative Literature had in essence stumbled upon a reference to the immigrants in Sandwich. It was through Robert Wilson’s play The Three Ladies of London (1581), an allegorical piece with two ‘good’ ladies and one ‘bad’ – Lady Lucre, whose dealing with an Italian merchant highlight how the property rental business to Frenchmen and Flemings is well-known as a means to ‘fleece’ the Stranger. Moreover, the list of towns given where this was most notable included some very specific Kent (and Sussex) places such as Canterbury, Dover, Rye and Sandwich.

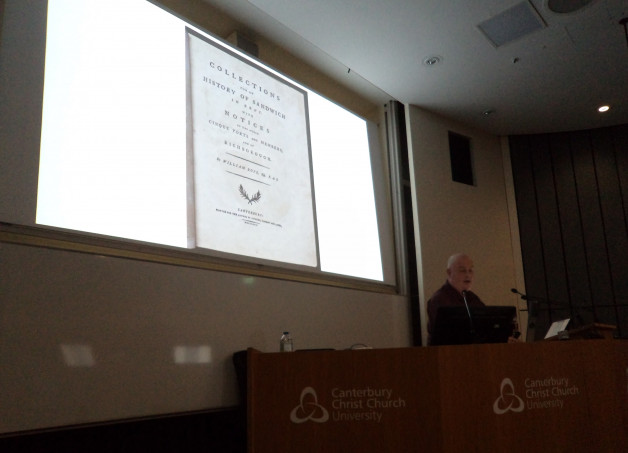

With this as his entry, Alan began his investigation by going to the three collected volumes of Tudor Economic Documents where he found a copy of William Boys’ copy from the Elizabethan State Papers of what is called in the volume the ‘Settlement of alien craftsmen at Sandwich in 1561’. Following the trail through the historiography on Elizabethan Sandwich and the place of the Stranger community in the town, he read Marcel Backhouse, who was in part following Joan Thirsk, as well as works by Michael Zell and Jane Andrewes and most recently the book by Sarah Pearson, Helen Clarke, Mavis Mate and Keith Parfitt. From these he gained ideas about where and how the Strangers had been able to settle and make a living in Sandwich primarily through the making of the New Draperies as certain lighter cloths were called, the presence of their own pastor, schoolmaster and physician, their use of St Peter’s church in the centre of the town, the absence of intermarriage with the local community, the way the civic authorities helped them to police their own community and that the Strangers were not intending to integrate with their English neighbours.

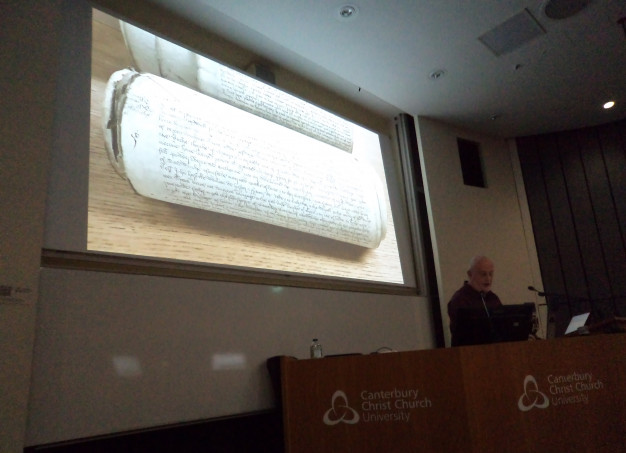

In some ways so far so good but in going back to the original documents he found that the story from Boys of how the Strangers were given royal approval to settle in Sandwich without difficulty following William Cecil’s advice did not fit what he was finding. Rather the evidence pointed to considerable disquiet among Elizabeth’s senior lawyers, Sir Nicholas Bacon as Lord Keeper of the Great Seal seeking a redrafting of the initial licence which, as Alan had also noted, is not precise in terms of the various numbers of immigrants cited. Furthermore, the process of gaining approval of the new royal licence was protracted, requiring the intervention of a host of senior ecclesiastical and lay individuals, including the Lord Warden, as well as the civic authorities at Sandwich and the elders of the Dutch church in London who were accommodated at the dissolved house of the Austin Friars. As Alan described, the matter required a whole series of sometimes delicate negotiations involving letters and various meetings, including the mayor of Sandwich making two trips to London between the summer and late autumn of 1561. Nevertheless, after something like a five-month delay Sandwich got its royal licence at some point between mid-November 1561 and mid-January 1562.

Yet, even before all the royal paperwork was in place, Strangers had been arriving in Sandwich, some from London but others from the Westkwartier region that straddles the French-Belgium border, who had been encouraged to come by their London brethren. Moreover, they had their own preacher in Sandwich, the Strangers given permission to worship in St Peter’s church. Interestingly, a high proportion of these migrants were servants, and the civic authorities might be seen as wasting no time to ensure that the New Draperies produced by these newcomers were meeting the required commercial levels within the town’s markets, thereby contributing to the civic purse. Thus, this bringing of the Strangers to Sandwich was hugely complex, drawing as it did on commercial and confessional issues.

However, Alan believes other issues were also at play which he sees as the foundation of the new grammar school and the desire to open up the harbour, that like other southern and eastern ports had been and continued to be badly affected by longshore drift, as anyone who has read Dr Chris Young’s excellent article in Maritime Kent will know.

Taking the school first, this might be seen as Sandwich’s response to a national survey which had highlighted what its Elizabethan official authors saw as an appalling shortage of grammar school because of the loss of Church-run schools (monastic and chantry).This was bringing ignorance and leading to decay in the university towns, and, of course, there was a shortage of educated clergy, the Protestant bastions of the new English church. Sandwich’s civic authorities responded to this call, but an even more enthusiastic champion was Sir Roger Manwood, who, having persuaded Archbishop Parker to release the necessary land to provide the site for the new school, took on himself the mantle of the school’s founder – and it is still named after him today. For contemporaries, Manwood’s role in all of this was celebrated by his friend and author Francis Thynne, and, as Alan acknowledged, this group of Protestant gentry with their written culture of letters, petitions, books and other documents produced in large part to promote Elizabethan Kent has been discussed by Dr Claire Bartram. Of course, this school foundation needed royal approval too, and in 1563 the value of education it was and would bring (even before it was built) had been espoused by its supporters, not least because education was equally treasured among the Strangers, who had their own schoolmaster. Thus, Alan believes this it not a coincidence but should be seen as linked through the network and ideas of the local leading citizens.

Similarly, he sees Queen Elizabeth’s progress to Sandwich in 1573 as having provided many of the same individuals with the chance to draw together these strands through pageantry, oration, banquets, gifts and something as ‘simple’ as ensuring the whole town was painted black and white and that the dignitaries’ clothing followed the same colour scheme. For Elizabeth, this 3-day visit was viewed as an excellent occasion and when the civic authorities requested royal aid to regenerate the town through harbour improvements, especially the creation of a New Cut from the haven to the sea, she was willing to oblige. Even though a number of Dutch engineers were employed on several occasions, success was limited, but notwithstanding that was hugely disappointing for Sandwich, that’s not the point from the perspective of who had greeted the queen so fittingly in August 1573, both natives and Strangers.

His excellent lecture was warmly applauded by the audience of staff and students from CCCU and MEMS at the University of Kent, as well as considerable members of the public, and the level of interest in the topic was obvious from the questions asked and the number of people who came up to talk to him afterwards – so many thanks to Alan Stewart for coming to Canterbury during his busy time as a Visiting Professor at Queen Mary, University of London.

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 2932

2932

Dear Sheila

This is an incredible summary. Thank you so much.

I was intrigued by the account of one “stranger” boy who had lessons in Dutch or Flemish at school, spoke to Walloons in the town in French and also conversed in English with other townsfolk. (I hope I have got that correct). I was wondering whether the grammar school was founded mainly for the education of the Strangers’ children or also for local boys. IF the latter then may be there were some lessons in Flemish and other lessons in English.

Thanks Ian, there were certainly local boys at the school, but others may know more.

The school was set up for local boys. I think the strangers would have had their own school as they didn’t mix with the locals. The original strangers moved away from sandwich because of conflict and went mainly to Canterbury or Norwich or returned to their homeland.

My ancestor Edmund Parbo promised to partly finance the school but I have seen his widow was prosecuted for reneging on the will.

Has anyone stumbled across William Bassett in the Sandwich archives? He was a Pilgrim in Leiden and said to be from Sandwich, Kent before 1620.

I am trying to confirm the alleged connection to Sandwich.

Can anyone help here? Many thanks in anticipation

Hi. There are no records for Bassett in sandwich 40 years either side of 1600. There is a William Bassett in nearby St. Lawrence. Born 1586 but married Sybil Sanders in 1609. But there are no burial records there for either.

I have the same request on the stumbling..for the name Lacet. It is written that upon arrival in Leiden,(Holland) het mentioned to come from Santwich, England. Please advise me where to look or to inquire. Thank you in advance.

Robert Th Lazet

Hello, you could contact Canterbury Cathedral Archives or the Kent Archives Service who might be able to help directly or be able to suggest someone who can.

I don’t know if you will see this as the other people haven’t responded. But up to 1603 no immigrants in sandwich had that surname. In Canterbury there was these 2 with the name La Set. When sandwich got to crowded the Walloons left and went Canterbury,Norwich and spitalfields. Holland is not a country it’s in the Netherlands.

Thanks Chris, always good to have more information for those interested in this subject.

Yes. I’m a bit obsessed. I winds me up people say they were huguenots when they were Walloons and French.

Thanks Chris, and yes good to differentiate between the different groups within those known as the ‘Strangers’. BW Sheila