This is just a short piece before we come to our busiest weekend of the year. Preparations are continuing and we are looking forward to meeting all our great speakers and those attending Tudors and Stuarts 2019, some for the first time and others who have become our ‘regulars’.

However, I did want to highlight other aspects of the Centre’s activities because Dr Diane Heath on Tuesday evening was at Lympne Village Hall where she gave a great presentation to SHAL (Studying History and Archaeology in Lympne). SHAL is an exceedingly busy and active local history and archaeology group, and it was excellent to be able to attend one of their meetings. For her presentation in the village hall’s new annex, Diane discussed ‘Medieval Bestiaries or Fantastic Beasts – and where to find some of them’ which drew on material from her doctoral thesis from 2015 ‘Bestiaries and Monastic Culture in Canterbury from 1093 to 1360’.

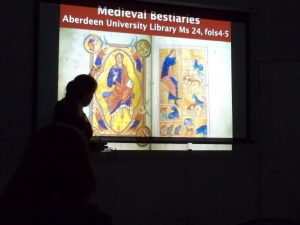

Diane pointing out Christ on the viewer’s left and Adam dressed similarly on the right naming the animals at Creation.

To give her audience an idea about what these books contain and why they were produced, she began by explaining that medieval bestiaries have a chapter per animal, although sometimes they are in pairs, and the information given was seen as literal but was also allegorical, moral and gave spiritual instruction – the four-fold senses – thereby making animals part of Creation, and bearers of emotional meanings. The producers of these Latin bestiaries drew on Physiologus and extracts taken from Isidore of Seville’s Etymologies, becoming ever larger as you move from the ‘First Family’ bestiaries of between 37 and 42 chapters, produced from about 800 to 1000 AD, to the ‘Third Family’ with their approximate 143 chapters and created between about 1200 and 1210.

The lion breathing life into his cubs [Oxford Bodl. Laud Misc. 247]

As a way of illustrating these various ideas, Diane explored specific animals as they are portrayed in these bestiaries and she began with the lion. Like all these animals they have certain attributes and the ‘second nature’ of the lion is that the male resuscitates his stillborn cubs on the third day after they are born – a reference to Christ’s crucifixion and resurrection. In addition, the ‘third nature’ of the lion is its watchfulness even when asleep, which too brings in the idea of the vigil between these Christocentric events. Over time more information was added to the bestiaries regarding certain animals and a further attribute of the lion became that it forgave penitent men.

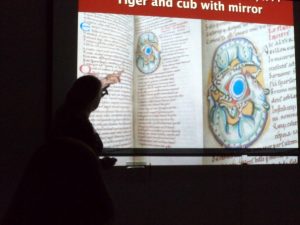

Some of the most colourful images Diane showed were of tigers and because the written description was not sufficiently explicit about the tiger’s fur, it is sometimes shown with spots and stripes or even a tartan pattern. Among the key features of the tiger is that if a hunter distracts the mother tiger by throwing a mirrored ball to her – seeing the reflection she thinks it is her cub – the hunter can then take away her cub. Such ideas were viewed as important by monastic communities and, as well as the portrayal of animals in the actual bestiaries, these same ideas might be deployed in other manuscripts to form letters, as here where the letter ‘S’ is formed from a sinewy tiger and her cub with a mirror at the centre.

Diane pointing out the beautiful tiger ‘S’

However, these animal ideas could also escape beyond the monastic boundary because they were similarly valuable notions for preachers – people would remember the animal, its attributes and thus the message. One animal that Diane discussed that was used in this way is the bear. According to the bestiary bears like sweet things in life – sleep, sex and honey (not sure if this is the right order!). They can stand upright and were viewed as representing ‘rough’ humans who, because they are not fully formed when they are born, being nothing more than a lump, have to be ‘licked into shape’ by their mother, which is where the phrase comes from.

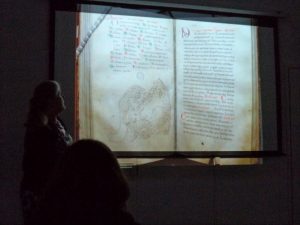

Diane showed bears being used in other ways too, and then turned her attention to the crocodile. Crocodiles caused these medieval artists many problems because the description mentions that only the upper not the lower jaw moves but there is not reference to it having a long snout. One way round this dilemma for one artist was to draw the crocodile with an upside-down head. When considering the nature of the crocodile, the bestiary notes that it swallows the hydrus (snake) and that after three days the hydrus bursts out of the crocodile’s stomach – a figure for Christ and the ‘Harrowing of Hell’.

Doves for breakfast, dinner and tea!

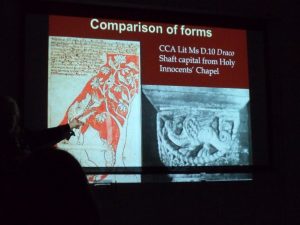

Keeping with a reptilian theme, Diane considered the dragon and that it is frequently portrayed sitting under the fabulous Perindens Tree in which doves nest, for if they leave the safety of the tree the dragon will devour them. Thus, we have the idea of the tree as a figure for the safety of the Church and the dragon is the dangerous Devil who grabs sinners if they leave the Church. Such dragons not only appear in manuscripts and if anyone has been to the Holy Innocents’ chapel in Canterbury Cathedral crypt, for example, you will know that there is a fabulous Romanesque carving of a dragon with glass beading along its spine and the wings linked to the legs – demonstrating the very high skills of the medieval stone mason.

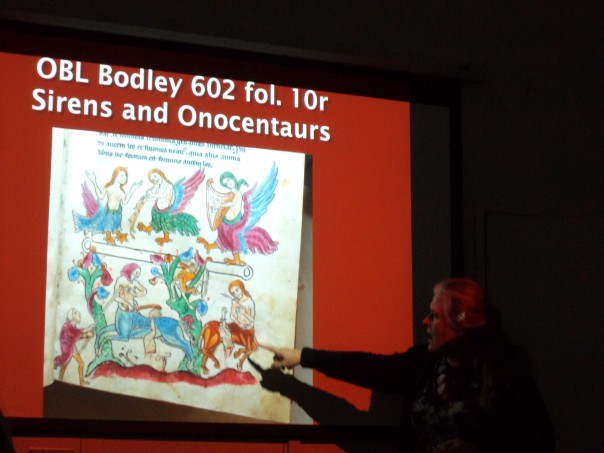

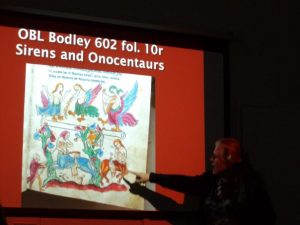

Her audience was obviously enjoying the presentation and among the other ‘fabulous beasts’ she discussed were the ‘leucrota’, the unicorn, the ‘cerberus’, the ‘chimera’, the ‘centaur’, the mermaid, the siren, the ‘onocentaur’, and to finish the oyster. This seems an appropriate one to finish on considering the local oyster industry at Faversham and Whitstable, even though from a medieval perspective the oyster is a stone that produces pearls. For at dawn the oyster opens and takes in the rays of the stars, the moon and the sun, as well as swallowing dew, and from these come the pearl.

Diane brings in more fabulous beasts

Drawing all these various threads together, Diane concluded by saying that medieval bestiaries were constructed by monks to explore their spiritual path, and then to take these same ideas outside the cloister through preaching to help the laity. Making animals fascinating and memorable were key features, and, as Diane explained to her audience, she is intending to use the same principles of accessing emotional meanings to help different groups of children as part of a funded project.

There were lots of questions after the long applause Diane received, and even more people went up afterwards to ask questions and to compliment her on a great lecture. Indeed, there were still people wanting to talk to her half an hour after she had finished speaking – a sign of a first-class presentation!

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 533

533