This week I thought I would catch up with what Dr Diane Heath has been doing recently, as well as where I and my fellow editors are with Maritime Kent. In some ways the later stages towards publication are more feasible at the moment, compared to the earlier part of completing research and writing where access to archives and libraries is extremely important. However, before I come to these developments, the CCCU Kent History Postgraduates met again this week.

Unfortunately Kieron Hoyle was unable to join us again because she is still suffering very badly from the virus, but everyone else was there and now that CCCU’s Teams platform lets more people on screen, all of us were visible to each other throughout our hour plus meeting. Again, we had a preliminary chat, which included the problem of haircuts and admiring Lily’s embroidery of a medieval pig, before we had our usual catch-up on how people are trying to work in what remain very challenging circumstances for history researchers heavily dependent on archival sources. As Dean was in the top left-hard screen shot, I’ll start there. He reported that he has been marking undergraduate essays for much of the last fortnight. However, he did say he has been thinking about the value of mapping the spheres of influence of the 13th-century Jewish moneylenders he has been studying. To that end he will be speaking to Lily who has been on a couple of digital mapping courses and, even though she didn’t include the maps in her thesis in the end, knows how to compile such maps. This was the first of the common themes that emerged during our meeting because Janet, Tracey, Maureen, and Jane are similarly considering they may want to use maps.

Lily, herself, has almost completed her responses to the examiners’ comments and is now looking at applying for post-doctoral funding. She has heard of a scheme that looks promising. It would seem to be a close fit to her interest in how archaeology has and can be understood (or misunderstood) by the media and the relationship between professional and amateur archaeologists. Jane continues to be handicapped by the closure of the county archives at Maidstone. Even though she has downloaded most of the monthly allocation of PCC wills allowed by TNA, the website is proving to be especially challenging on some occasions – the problems of technology! She is also continuing to read about monastic hospitality, and for one of her archival documents, it is possible Dean’s friend can help because it is in Medieval French. Peter remains extremely busy with his work as part of the CCCU chaplaincy team and helping the local community. However, he has now submitted his MA thesis having responded to the examiners. He is also exploring the use of Flipbook as a source of material for teaching, as well as in relation to issues surrounding mental health and wellbeing, matters that he thinks will be especially pertinent for students in the coming academic year. Tracey has completed the revision of her draft introduction and is compiling documents that correspond to her three main chapters with material from her research. She will then have a good idea of what is missing and what she will need to investigate in the next stage of her project. With the departure from CCCU of Dr David Grummitt, Janet now has Dr Leonie Hicks as part of her supervisory team. To show Leonie how her thesis is progressing, Janet has sent her several files covering what she has been working on recently. Among the topics she is currently exploring is medieval parks and recreation in the Scadbury area, especially the relationship between such spaces and their uses, and the role of Londoners in this part of north-west Kent. While mapping is an issue, so is the value of databases for historians, which was another common theme that several people felt they would like specific training on. Maureen was one of those who would like this, especially after the course at the IHR she had signed up for had had to be cancelled. She, too, is hampered by the loss of access to archives, in her case the Staffordshire Record Office and Canterbury Cathedral Archives & Library. However, she has been writing up the detailed work she has been doing on the Tonbridge accounts. This means she now feels better placed to take a step back and appreciate how this material can be deployed to tackle her research questions concerning the ongoing relationship between the lords of Tonbridge and the people of the town. Thus, as I hope you can see there are lots of exciting research projects here.

I’m going to turn first to Diane’s activities because she has been busy working as the series editor for ‘Medieval Animals’, which is produced by the University of Wales Press. Some of you may remember the Introduction to the Medieval Dragon by Thomas Honegger which is a fabulous book and even features a flying dragon: https://www.uwp.co.uk/book/introducing-the-medieval-dragon/ well the next in the series will be out in September. This has meant Diane has been editing the Introduction to the Medieval Ass by Kathryn Smithies, who is a medieval historian at the University of Melbourne https://unimelb.academia.edu/KathrynSmithies . Now some of you may be wondering whether the ass really does have a fascinating history, especially compared to dragons. However, the short answer is that it does. For Introducing the Medieval Ass explores this fascinating animal’s social and cultural significance in four key areas: nature, religion, scholarship, and literature. These carefully chosen themes have allowed Katheryn to explore crucial primary sources to investigate the ass’s heavy socio-cultural burden (Diane’s pun so no excuses from me!), such as its labour and its assumed characteristics of irrationality, humility, stubbornness, and sexual perversion.

Among the exciting aspects that you will be able to discover from this book is that during the Middle Ages, the ass became synonymous with human idiocy. Not only could the ass be envisaged as representing students who were too dull to learn, but comedy was equally applied to their asinine teachers. This idea of linking the ass to irrationality continued well beyond the Middle Ages, which meant that by the 18th century the word for the animal had to be replaced by ‘donkey’. Throughout the medieval period and beyond, indeed still in many parts of Europe, Africa, and Asia, the ass was a vital, utilitarian beast of burden. So economically it remains a vital component in many societies, although, as Diane suggested, probably in the UK the ubiquitous white van is its nearest equivalent! Nevertheless, in medieval times, culturally the ass enjoyed a rich, paradoxical reputation: its hard work was praised but its obstinacy condemned. Taking this further, Katheryn explores how the medieval ass exemplified the good Christian by humbly bearing Christ to Jerusalem, but it also represented Sloth, a mortal sin. Its sexy reputation was linked to sterility, as well as unnatural mating with the horse to produce the hybrid mule, a term that equally has entered into the English language for other meanings beyond the animal itself. I hope you are beginning to see just how fascinating this animal is, as well as now necessary the humble ass was for medieval people. Consequently, Diane is fortunate to have another great book for this series in which Katheryn presents a lucid, accessible, and comprehensive picture of the ass’s enormous socio-economic and cultural significance in the Middle Ages and later periods.

I hope that you can see how exciting this series is becoming and I believe other animals that are on their way include the Medieval Swan and the Medieval Snail, and when I get the time it is just possible they may be joined by the Medieval Pig, as well as by Diane’s own study on the Medieval Bestiary.

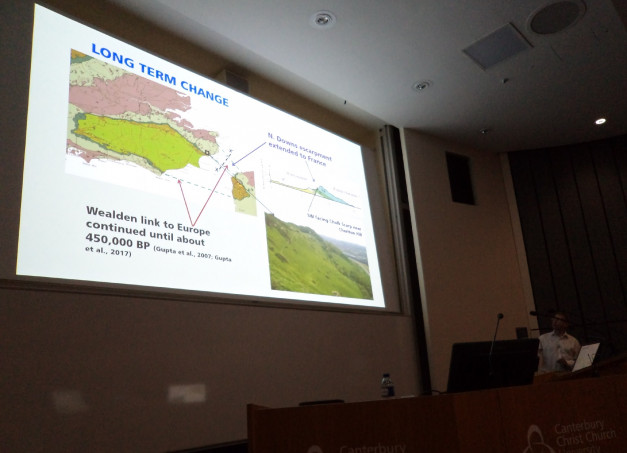

But to get to back to one of my current projects, as editors Dr Elizabeth Edwards (retired University of Kent), Stuart Bligh (Royal Museums Greenwich) and I had another meeting this week to discuss matters surrounding how the different sections: ‘Topography’, ‘Defending the Coast’, ‘Trade and Industry’, ‘Coastal Communities’, and ‘Case Studies’ are coming together now that we have gone through almost all of the chapters and have offered comments and suggestions to contributors. We have also fine-tuned the various sections, looking at word length and the desirability of moving a couple of chapters about to give a better structure to the entire volume. For example, we are happy that Dr Christopher Young’s (formerly Geography at CCCU) substantial chapter on the changing coastal landscape speaks to many of the other chapters, providing a vital context for the county’s maritime history, as well as exploring its pre-historical past.

Moreover, this fine-tuning has similarly helped regarding matters of balance. Consequently, we now have four chapters exploring ‘Defence’ from late Roman times to the modern era; five for ‘Trade and Industry’ that cover Roman to Modern Kent; and four under ‘Coastal Communities’ that take us from the Pre-Conquest period up to modern times. As you would expect, many of these speak to each other both within their sections and across the different themes. This complementary approach greatly enhances the volume, as does the setting of these chapters in contexts that go beyond what might be seen as a narrow inward looking stance by the contributors, who are keen to see ‘Maritime Kent’ beyond the county’s shores and how Kent fitted into the wider national, and at times international picture. Thus, for example, Dr Ben Marsh (University of Kent) and Professor David Killingray’s (retired Goldsmiths, University of London) exploration of Kent’s involvement in the Slave Trade takes us to the Americas; while Professor Maryanne Kowaleski (Fordham University, USA) draws on her exceptionally wide and detailed knowledge of maritime economies to explore the diverse Kentish marine-related trades and industries in the Middle Ages.

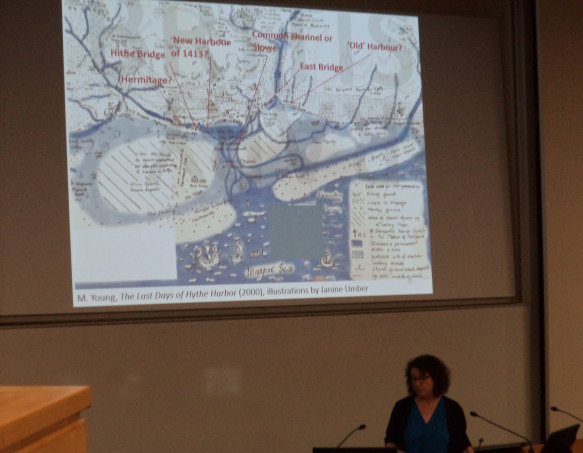

Nor is this all, because unlike some other English maritime county volumes, we have a section that highlights recent research through a series of case studies from the late medieval to the 20th century. By focusing on specific ports or topic at certain times, the authors are able to showcase the rich and diverse sources available to study maritime Kent, whether we are talking navigation manuals, local taxation records, wills, marriage licenses, poetry, novels, personal letters and journals, and official government directives and correspondence. Also, as I hope you can see, some of our contributors are going beyond what would normally be envisaged as ‘historical’ sources and this use of literary texts offers a multidisciplinary aspect to the collection, most particularly in the case studies by two more CCCU academics, Dr Claire Bartram (now a co-Director of CKHH) and Professor Carolyn Oulton. Furthermore, as well as geography, the volume draws on archaeology, including contributions from Dr Elizabeth Blanning (University of Kent), Dr Andrew Richardson (Canterbury Archaeological Trust) and Mark Harrison (Historic England).

Returning to our editors’ meeting, now that chapters have gone back to contributors, our next task is to write the Introduction, and having sketched out how we think we should do this and allocated various tasks, we have now gone away to do that before our next meeting. For among other issues, we want to use the introduction to flag up much of the work that has already been done on maritime Kent and to highlight where our volume complements and takes research further to gain a greater and more nuanced knowledge and understanding of this aspect of the county’s long history.

So things seem to be falling nicely into place with the idea that the manuscript will be going off to Boydell at the end of September this year. With that in mind we have fortunately gained two sponsors for the volume, the William and Edith Oldham Charitable Trust and Kent Archaeological Society. From a personal perspective, I think this is important because such organisations thereby underline their commitment to the production of good and worthwhile history of the county, that at the same time is not confined by narrow local or regional inward-looking perspectives, but places, as in this case, Maritime Kent in a national, even global context. Indeed, this was apparent at the ‘Maritime Kent through the Ages’ conference we (CKHH, Royal Museums Greenwich, KAS) held in 2018 and seemed to be greatly appreciated by the audience. Thus, like the Medieval Ass, I’ll let you know how matters progress.

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 2576

2576

I am a trustee of the Seaside Museum in Herne Bay and was interested on your work on Maritime Kent. I am not sure if you can help me but I am trying to find out more about the origins of the Herne Bay which was a very early ‘new town’ for those who wanted to live away from the smoke and smells of London but could afford to travel up and down the Thames by paddle steamer. Herne Bay was planned and developed around the pier and the paddle steamers Red Rover and City of Canterbury by a group of the developers who formed the Herne Bay Steam Packet Company to build and run them. Both steamers were built in 1835and I strongly suspect that much of the money came from compensation paid in the early 1830’s to owners of slaves in the British Empire. The City of Canterbury was running up and down to London until the 1860’s. The story of the Red Rover is fascinating and includes her sinking in a collision off the Nore in 1836. She was raised and put back into service but disappears from the records around 1849. I would be grateful for any advice you could offer me on where I might find the records of the Herne Bay Steam Packet Company.

Hello David

That sounds very interesting. In terms of Victorian steam power, I would suggest that you try contacting Emeritus Professor Crosbie Smith at the University of Kent. His email from the Kent website is c.smith@kent.ac.uk

Thinking about the relationship between possible funding from compensation, I would suggest that you might try contacting Dr Ben Marsh at the University of Kent. His Kent email is: B.J.Marsh@kent.ac.uk

I wish you success with your research.

Best wishes

Sheila

Sir,

I am interested in the history of the steam packet “Red Rover”, which was equipped with a steam engines manufactured by Boulton & Watt, see “the steam engine:: its invention and progressive improvement .., volumes I and II” by Thomas Tredgold London: John Weale 1838. He mentions: “PLATE XXX.

In 1816 a vessel (Caledonia) was purchased by Messrs. Boulton and Watt, and

fitted with two engines of fourteen horses’ power, solely for the purpose of making

experiments under various circumstances and modifications of paddle wheels. One

of these experiments embraced the ascension of the Rhine in the winter of 1817 as

high as Coblentz.

The plate represents a side view of the engines manufactured by Boulton and

Watt for the Red Rover and City of Canterbury steam vessels. This form of marine

engine adopted by them about this period, say 1817, was fitted on board the Favourite

in April 1818, and, with the exception of some slight improvements principally

made by themselves, it still remains unchanged.

In the first edition of this work it was stated in mistake, that they had adopted it

from the Clyde. This is incorrect, and we take the present opportunity of stating

that this mode of construction is due to Boulton and Watt, and that a preference has

been given to the arrangement by several of the best makers who have followed it.”

and

It may not be irrelevant to notice here, that owing to this mode of securing the engines the proprietors

of the Red Rover were recently enabled to raise that vessel when sunk in forty feet water.

The principal chain which lifted her being secured to the frames of the engines, it having given way

when fastened to the vessel itself. It is the practice of some makers to bolt only through the sleepers,

which we by no means consider so secure.”

and

“HERNE BAY STEAM PACKET RED ROVER.

The engines, two 60 horse power, are by Messrs. Boulton and Watt, and the

vessel was built by Messrs. Fletcher, Son, and Fearnall, London ; launched 28th March,

1835, for the Herne Bay Steam Packet Company.”

etc

on https://military.wikia.org/wiki/List_of_shipwrecks_in_1836 was mentioned that the Red Rover foundered on 17/10/1836 after colliding with the steam ship “Magnet”

Do you know what happened with the Red Rover after it was refloated?

Best regards,

Guy Janssen

Hello Guy

Sorry I don’t know the answer but have you tried contacting Mark Harrison at Historic England who works on the history of this part of Kent’s north coast.

Best wishes

Sheila

Hi Guy,

I have just picked up your enquiry on the fate of the Red Rover. On the collision with the Magnet she sank, close to the Nore lightship, in the middle of the main Thames shipping channel both to London and to the naval dockyards at Sheerness and Chatham and was a major hazard to shipping. The Admiralty loaned two specially equipped barges to the owners and she was raised within a week of the collision with the help of divers from Herne Bay and Whitstable. She was taken into Sheerness dockyard, patched up, and then towed up river, probably to the shipyard of Fletcher, Son and Fearnell at Limehouse where she was built. She was repaired and back in service a year after the collision sometime towards the end of 1837 and remained on the London – Herne Bay – Margate run until 1851 or 1852 when she was sold, probably to the General Steam Navigation Company which bought up a number of second-hand ships to ship cattle in the UK from the Continent. The new owners refitted her by stripping out the paddles and replacing them with a new engine and screw propellers. Unfortunately, she did not survive her first run to the Holland to pick up cattle as she was caught in a severe storm and beached close to Schevenegen and that was the end of her.

Thanks David for responding to Guy’s request, that’s all very helpful – a sad end for the Red Rover.

Best wishes, Sheila

Dear Sheila,

Many thanks for you helpful suggestions.

Sincerely

David