Some of you may remember that about 15 month ago the Centre held a conference on ‘Maritime Kent through the Ages’. Following that successful day Stuart Bligh, Dr Elizabeth Edwards and I decided we should capitalise on the interest shown and edit a collection of essays under the same heading. Since then we have made considerable progress and I thought I would let you know that we are in the process of receiving essays from 23 contributors, including Professor Maryanne Kowaleski (medieval trade and industry), Dr Sandra Dunster (early modern coastal communities) and Professor Andrew Lambert (modern coastal defence). In terms of the publisher, we are continuing to work with Boydell and without wanting to jinx the project, things are looking promising on all fronts, so more details as matters progress.

I’m also continuing to work on the Medieval Canterbury Weekend 2020 and in addition to the speakers mentioned last week, among the others who will be at CCCU next April are Dan Jones, who will be discussing research from his new book on crusaders, and Professor John McGavin, who will consider ideas about late medieval drama in terms of performance and spectatorship that are relevant today. We are also fortunate to have Dr Catherine Delano-Smith. She will examine that fascinating medieval cartographic work, the Gough Map, while Dr Sophie Page, an expert on medieval magic, will explore cultural aspects of this subject. More details soon and as I said we hope to go live with all the details in early October.

Lady Wootton’s Green today

Having mentioned St Martin’s Priory last week, I thought this week I would come down to the other end of the CCCU site and give you a few details about Lady Wootton’s Green for about the same period. So what do we know about the area outside Fyndon’s Gate, the Great Gate of St Augustine’s Abbey? Well firstly by the early 17th century it was known as Mulberry Tree Green or Mulberry Green/Common or Palace Green, while the area around the what had been the abbey’s almonry was sometimes called Amery Green. Interestingly there was a further variant with respect to Mulberry Tree Green because the area was also occasionally listed as Lordes Common.

It is not clear when the mulberry tree was planted but the tree was mentioned in the 1591/2 city chamberlains’ accounts and a few years later William Hamon of Westbere was indicted for assaulting Anthony Harrison at ‘le Mulbery tree’ in St Paul’s parish. This may imply that the tree was in an open space, a view apparently endorsed by the map evidence, which meant it was probably adjacent to that other piece of open ground, called by some the ‘Ambrey’ ground, and the place where William Greeneland and his accomplice were caught stealing a sheep in 1596.

From John Brent’s Canterbury in the Olden Time (1879)

By the same period the Green had become an enclave for several Welsh families who maintained their own language and customs, and the presence of this apparently poor immigrant group may suggest the marginal nature of the area, due in part to the loss of the abbey. For even though the abbey would quickly become a minor royal palace, initially in the post-Dissolution era it became a quarry for building stone, and some buyers in 1552-3 carted away tons of rubble as well as high quality Caen stone, while Mother Chapham paid 12d for two cart loads of flint and rubble from the old steeple and other places. Access to what had in effect become a builders’ yard was through Fyndon gate, which must have caused considerable disruption for those living and working in the area. Moreover, once rebuilding started on the creation of the king’s apartments within the abbey precincts further disruption was presumably inevitable, and it seems likely the saw-pit was also located in this area, which may be commemorated in the neighbourhood today by the ‘Two Sawyers’ public house.

Going back to the naming, the term ‘common’ may more accurately describe the land because it was ‘waste’ land in manorial terms, an area often used for communal gazing having little agricultural value. It was part of the Barton or Longport manor, which was said to contain twenty messuages, two tofts, a dovehouse, twenty gardens, 430 acres of land, fifty acres of meadow, 120 acres pasture, fifteen acres woodland and 50 acres of heath and waste, including the Green. Yet this did not mean the steward of the manor didn’t care about it and the solely surviving court book has numerous entries about the Green. Beginning in 1627, one of the early entries notes the continuing encroachment by the heirs of Edward Wootton ie Lady Wootton upon the king’s highway and upon the waste of the manor between St Augustine’s gate and the pond called Court Sole. The ‘heirs’ were to remove the fencing they had put up, which was contrary to ancient custom, or they would be fined 40s. A few years later, under 1632, Lady Wootton is named as the culprit. She was said to have erected fencing on the king’s highway, leading from Broad Street and on the manorial waste, that is Mulberry Tree Green, to Longport Street. This obstruction had been there for twelve months and she was to see to its removal within twenty days or face a 100s fine. To make matters worse she had also obstructed the common watercourse, between Mulberry Tree Green and St Augustine’s Gate, and the same watercourse along Longport Street, the first offence carrying a very heavy penalty of £60, suggesting its seriousness and the exasperation of the court officials. Furthermore, she was setting a very bad example to her far poorer neighbours, people like Richard Pising who had left his timber on the Common or Green, and Widow Hawkes, who was extending her ground by fencing in part of the Green next to her house. Both were to remove the offending items within twenty days or face a fine of 5s. However, Lady Wootton seems to have treated the court with contempt and over the next twenty years she was a habitual offender as she (or her servants) sought to extend her property by fencing in part of the Green and the highway, which was constantly to the detriment of the common watercourse. It was also to the disadvantage of the local people who used the Green as a common way, as their ancestors had done for centuries.

The site of the almonry of St Augustine’s Abbey – CAT have excavated there

The death of Lady Wootton removed the chief offender, and after what had become known as ‘Lady Wootton’s Palace’ passed into the Hales family through marriage, it was let to a succession of lessees whose names are not recorded in the views of frankpledge for Longport for such ‘crimes’. These people, at least in the early eighteenth century, were local, like John Willesden, a fruiterer from Longport and Elizabeth Mayne, a widow, and her son Edward, who was a gardener. Their neighbours, however, did continue to encroach upon the Green: John Kingsford of Canterbury, milliner, enclosed an area four rods long by half a rod in breadth in front of his house in 1677and his son?, Samuel was similarly indicted in 1727. One of Samuel’s neighbours, George Knowler was also in trouble with the court, because he had not only erected several posts but had planted trees on the road next to his messuage (the Knowler family held the Almonry). For others the area offered further opportunities. John Knockers seems to have built himself a small messuage and garden upon the waste, in this case on part of Palace Green, his successor, William Swift, paying 5s a year in rent. Such individual enterprise was at times tolerated (even encouraged?) if it brought in extra revenue, but the manorial officials were also keen to regulate issues concerning the common good. Communal responsibility was the cornerstone of their policy and in 1677 the whole borough was indicted for not repairing fencing alongside the common watercourse, and three years later the tenants faced a fine of 20s if again they failed to make the necessary repairs.

Moving to the early 19th century, William Harnett the elder, gentleman, came from Lady Wootton’s Green, presumable residing in one of the largest houses there and from Charles Dickens’ David Copperfield it appears the Green was seen as suitable by the professional middle classes. Even the ghost was respectable, in 1964 it was reported that many years before a tall, elderly man, wearing a cravat but no hat, had been seen pacing up and down at night in the long passage beside the Almonry. However, the building boom of the Victorian period and, in particular, the opening up and extension of Canterbury’s suburbs for development probably meant that the late medieval/early modern houses by the Green lost much of their appeal, except to rent out, becoming the homes of artisan families and working class tenants. Yet, as elsewhere in the city, mixed housing/status neighbourhoods remained, and Lady Wootton’s Green seems to fall into this category. In addition, the same period saw the foundation of St Augustine’s College (1848) thereby preserving the abbey precincts as an entity, its new use as a training college for Anglican clergy preserving the link with its monastic past, a stark contrast to the development of St Gregory’s in neighbouring Northgate, which became a honeycomb of Victorian tenements.

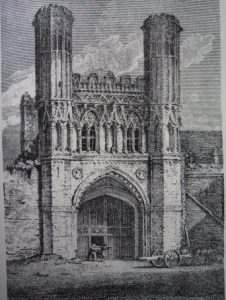

Fyndon Gate – another of Brent’s illustrations

Changes also occurred at the Almonry. In the mid-eighteenth century it had passed out of the hands of the Knowler family to Howard Bridges, esquire, of Wootton, and a century later, in 1854, the devisees of the estate of the late John Prier, included the Almonry among the properties to be sold at auction. The purchase price was £325 but the yearly rent provided almost a tenth of this (£30 11s). Among the seven heads of household of these six tenements was John Booreman, carpenter, who like his next-door neighbour, Matthew Fox, a shoemaker, had been there since at least 1841. Many of their neighbours were less affluent, like Ann Lines, aged 76 in 1851, who was living on parish relief, Margaret Middleton, who took in laundry and John Wotford, a general labourer. Those outside the Almonry in 1841 included the families of Robert Royle, sawyer, and John Kensey, colt breaker, and, even though a decade later the Kensey family had gone, Henry Royel seems to have taken on the same business. Higher status families, like Captain William Plummer who called his house ‘St Augustine’s House’ in 1891, continued to form a minority of the local population during the late nineteenth century, but by 1901 such families were generally living in Broad Street or had moved to the new, fashionable houses in places like St George’s Fields (New Dover Road), leaving Lady Wootton’s Green to people like Clara Holness, a widow with one child who took in laundry and lodgers, Edmund Ballard, a farmworker with a daughter and granddaughter, and Stephen Best, a tailor, living with his two adult children.

Perceptions about the area, especially those held by Canterbury’s leading citizens, can be gauged from the actions of the St Augustine’s College authorities in 1896. As the new owner of what he described as two or three dilapidated cottages situated at the Broad Street end of the Green, and covering a large part of the area between the houses to the south and north, the warden, on behalf of the college, wrote to the city authorities saying that he now intended to demolish them. This was a costly undertaking because in addition to the purchase price and demolition expenses, the college would lose £24 14s a year in rent. Nevertheless, he was prepared to organize this because it would provide an open vista of the college gatehouse and cathedral, a pleasing prospect, and would allow the college to provide a garden ground, planted with trees and shrubs, and a pleasure avenue for the general public. The mayor and corporation were enthusiastic backers of this proposal, contributing £150 from city funds, and the Kentish Gazette similarly endorsed the improvements, reporting in 1897 that there was now two carriage ways surrounding a central avenue ‘with suitably designed wrought iron railings’. The reporter also commented on the central gravel walk, the flower borders, the ‘cast iron posts of oriental design’ and the widening and reforming of both carriage ways in ‘granolithic cement’. The only remaining blot on the landscape was the cowshed which abutted the city wall. This building was a legacy of the corporation’s earlier policy of leasing out the city ditch and its subsequent selling of the area when such matters were finally allowed by Parliament in 1836.

Fyndon Gate today – now the entrance to one part of the King’s School

Bombing of the area during the Second World War led to heavy property losses around the Green, but much of this garden ground survived and today there are the additional statues of King Ethelbert and Queen Bertha, reminders of the area’s links to its ancient Anglo-Saxon past and to the abbey and St Martin’s church as two parts of Canterbury World Heritage Site, which includes the CCCU campus as the abbey’s outer precinct. And next week I’m hoping to bring you more about the the county’s Anglo-Saxon past.

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 2427

2427

Excellent article which ties in very well with some groundwork i investigated over the last few years. I was wondering if i could copy this or add a link to my Facebook group

Canterbury Remembering It As It was. Which is well known for promoting the history of this wonderful city

Thanks for your comment, yes certainly link it or copy to your Facebook group.